In Brontez Purnell’s prolific and varied ways of working, single moments act as dream holes into the entirety of a personal cosmos. For the past year, I have been working with a group of amazing teenagers through the Dia Art Foundation and New York City’s Department of Youth & Community Development program. Under the rubric of thinking about and making art, the program supports young people in realizing their capabilities to act creatively within and upon the world. When I was thinking of who could visit as a guest artist, to shake up the group, Brontez was the first person who came to mind. Before he arrives, we do a highly-curated online crawl; avoiding anything explicitly sexual while still attempting the full tour of his oeuvre, I lead them through music videos for his punk band, a trailer from his dance documentary, excerpts from his writing and a scene from the screenplay Brontez and I are adapting from his 2017 novel, Since I Laid My Burden Down. In cruising Brontez’s impressive CV, I want to impart to the group the only sure thing I know about being an artist: nobody lets you be one—you make yourself into one. “He founded his own dance company!” I tell the teens. “He’s published at least three books but started by making his own zine! He’s toured with his bands all over the world!” They seem excited but confused. I hear myself saying, “He’s not a plate spinner. How could one person make all of these kinds of work?” We untangle this question further: what is this artist obsessed with?

We start with the Super 8-shot music video he made in 2010 for the song “Keeps on Falling Down,” performed by his band, The Younger Lovers. On screen, a group of queers and punks gather in a cluster to do a series of dance moves along a sidewalk in Oakland, California. Each move is pre-announced on a white piece of paper that is slid in front of the camera: Squash the Bug, Sick Twist. The video feels like an invitation to the viewer: do you want to dance, too? I do. Once I’m at home, alone, I put the music video on again and start to dance casually—three beat moves on a four count. I play it only, say, about 100 more times—I follow along, tracing the movements and feeling the names of each one in my body, relishing that pause that floats in between each repetition.

Our first workshop is in the basement of the Judson Memorial Church, around the week of Valentine’s Day. He arrives with his cousin, to provide live saxophone accompaniment, and a lover, responsible for manning the projector and tech. He begins with an exercise called “Entrances and Exits” and asks us each to brainstorm three declarations to propel us through space. “Entrances and Exits” presents an existential challenge: can’t the two always be exchanged, depending on where you are, and how you are thinking about it? But before any of us have the time to pause and overthink, we are off, walking in and out of the three doors of the room, punctuating each boundary with one of our prepared lines. First we move at our own paces, trying out different tones of phrases like, “Why, Why, Why, Why?,” “My Whip!,” “Not today, Satan!” and “Happy New Year!” We rev and slow, adjusting the statements as we move. The music Brontez’s cousin is playing and the squeak and swish of our sneakers on the Formica tiling blend with our mantras and the result is beautiful, chaotic noise—it’s impossible to feel self- conscious, there is just too much sensorial action going on. Eventually, we collectively ramp up into fever pitch, moving faster, bumping into one another, screaming and laughing as we enter and exit, saying things with the fervor of maniacs. By the time we stop to do a twenty-minute Sylvia Plath writing exercise, we are all sweaty and completely over whatever awkwardness we were feeling before we started. Each of these moments opens up new moments, shows us what is possible, shows us how we are alive, huzzah!

Here’s another dance move, with a title card that could read “Daddy.” In Brontez’s upcoming book 100 Boyfriends (out February 2), a young boy named Mickey watches as his Daddy, pronounced Diedee, goes through the beauty rituals for attracting a new step-mother, starching a crease in his jeans so sharp “you could fuckin’ cut ya self on ‘em” before leaving for the bar. Waiting for his father to get home, the signature smells of pork cracklings, alcohol and cheap cologne lingering, Mickey practices his Flashdance and Janet Jackson routines, wondering whether drinking water from a bottle and living in a loft are the keys to a successful, high-femme life: “Is this a thing?” This particular Daddy admixture of absence and presence shows up in Since I Laid My Burden Down, too; the narrator, DeShawn, swims in the smell of pickled pig’s feet, cologne and liquor, this time while cleaning up the Harlem apartment in which his father died alone.

Brontez has coined this retracing throughout his work as “the Art of the Recyclable.” Many of his stories appear and reappear in different iterations with a detail exchanged, one part drawn out or frosted over in order to get to the next part of the narrative this time. This is where his writing feels profoundly based in conversational storytelling, usually passed on, much like dance, from one body to another, but this time it’s committed to paper. Life is often sort of like this, but we don’t always record all of our iterations. We retell the stories of our lives from different angles, often depending on our mood and who we are talking to. Sometimes the distinguishing note is that of creamy fried skin and, at other times, that of a vinegary pungency.

In the circle that Brontez has cast around his work, the queered term “Daddy” stands in for, connects up with and blows the fuses of notions of legacy, lineage and inheritance. Daddies of all kinds abound. Daddies who make you feel seen and daddies who don’t, daddies who pay you and daddies who disappoint you, daddies who donate their DNA on, in and around your body. Legacy can be growing up in a Baptist church, then becoming a performance artist. Legacy can be inherited from your creative elders, as exemplified in Brontez’s documentary about San Francisco dancer Ed Mock. In “Free Jazz,” a work spanning 2010-2012, legacy feels like an interactive, involutional space. Through structured improvisation, Brontez creates a map of his own body’s learning—Haitian, African, Anna Halprin and the Isadorables—moves that were passed through generations of bodies that meld and bake with the choreographies of his particular consciousness of the everyday, offered as his own recording for the next to pick up and shift. Legacy can also be passed on from one family member to another. An assortment of coats and guns in a deceased father’s tool shed in Alabama, much desired but only half-collected, after a decision to never set foot outside of California again. Legacy can be an inherited sense of fatigue from your grandmother, externalized as a man in a pink suit skulking around your family’s house in order to take advantage of the young girls in your family, but dealt with abstractly, like weather that you can’t really change but can definitely make a point in avoiding. Legacy can also be the rude fact that your father insists that a werewolf can always come and get you at any minute, even if you are holding your daddy’s hand. Perhaps legacy can even be likened to an STD; you and a bunch of your friends all fucked the same neighborhood guy and all have the same burning sensation in your pee hole to prove it. Legacy consists of all of the discrete moments that are usually never recorded, that often blur together—in the public restroom or in the bathhouse waiting with a towel on your head—that can potentially be reconstructed through fiction, like some sort of psychedelic captain’s log of the seasons of one’s life, but adding up to what exactly?

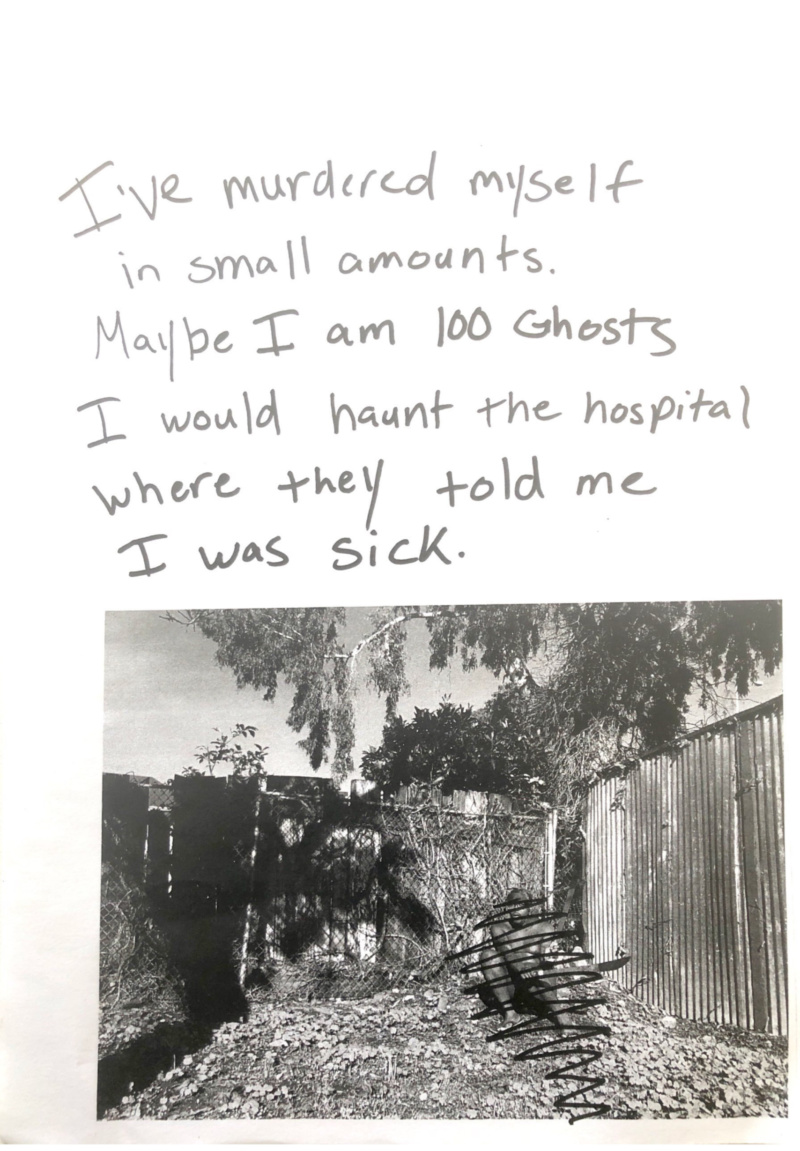

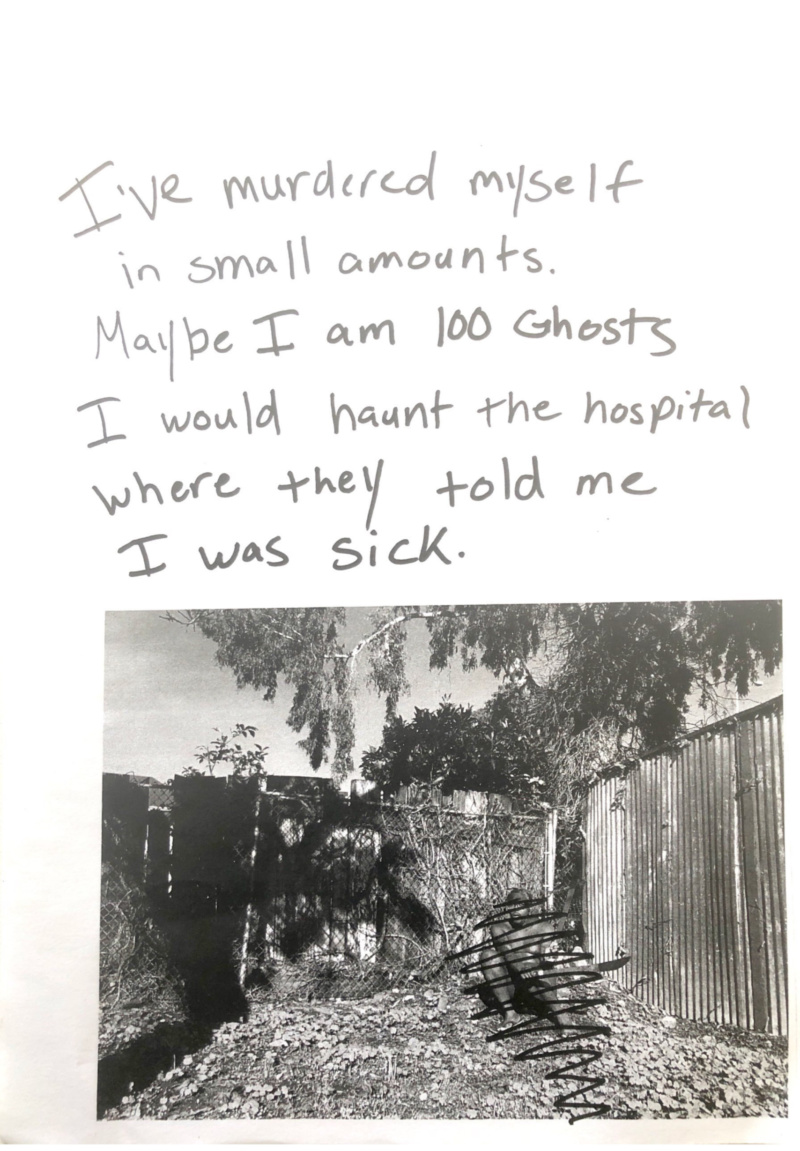

This is the question that 100 Boyfriends asks. Starting with the epigraph, “Fuck All Y’all,” the book proceeds from that slap to a readerly seduction, sharing with abandon the narrators’ most intimate loves, hates, disappointments and excitements. If 100 Boyfriends reads at first glance as a procession of hangovers and unruly lovers, its structure is, in fact, a provocation. There are few narrative possibilities afforded to queer Black men “out there” and, in this way, the book thwarts those cliches head on, simultaneously throwing the reader into a quickie frisson while letting them dangle in the actual uncertainty and exhaustion of these moments. The narration slips between characters like a baton being passed in a relay race. Not between any and every character under the sun, mind you— these stories are told specifically from inside the consciousness of a Black man or child sitting in and between different intimacies with other men, or lack thereof, Brontez counters. Here are all the old scenes that somehow feel different this time, or all the new interactions that feel like the same old shit. 100 Boyfriends acknowledges that every moment spent fucking a stranger is discrete, is its own mysterious chapter, full of projection, and does not necessarily lead you to knowing yourself or someone else better. It gathers and disperses moments like the lungs of a body panting shallow breaths, which is really all the form you need.

The refusal to cohere with linear narratives across all of Brontez’s work is paired with an equal insistence on cracking jokes. If it’s all the same old shit, why not make it more entertaining, both for yourself and for whoever happens to read it? Brontez’s Instagram contains some of the most trenchant punchlines, such as one of his posts from this past summer, which reads: “Child please, I was born canceled.” He ponders, in conversation, “At the end of my revolution, there will be all kinds of reformed criminals. It’s not going to be a room full of people who all have squeaky clean reputations. That sounds like a living form of hell.” In another post, a video of Brontez, he appears in underpants and a collar, being led around a kitchen on hands and knees by a lover. He makes direct eye contact and wags his tail as the voice off-camera tells him he is a good “boy.” Below, his caption reads, “BLACK LIVES MATTER” and “BLACK KINK MATTERS.” Is it not true, dear reader?

As a self-declared intimacy hound (which is just another way of saying you have slutty energy), I might be projecting when I say that a large part of Brontez’s practice strikes me as operating in a similar fashion; being a slut is a mode—rather than “Why?” you ask, “Why not?” Ever reaching for your own limits, you cast your net wide and wait to see who or what might come your way. Often enough, this mode in turn casts you, slut protagonist, into a process of disassociated, omniscient narration. You watch yourself as the action comes sidling up to you; you are your own personal object moving through the world— what might happen next? Brontez builds in the structural spirit of punk and queerness; these are moments typically not in service of a hyper-productive trajectory of successful living and that do not inherently build towards getting “wifed up” and living a more “normative” life. Instead, these moments unfurl with the rhythm of being alive and they insist only on themselves. And, as much as the narrator says that he might want to be a wife, replete with a watermelon farm, every time he comes close, he feels fatally bored and opts instead only to give himself over completely to johns and already-married (or -heartbroken, or -self-destructive) men. Not choosing but being chosen is key, however; in the politics of being a slut, choosing your own entrances and exits is essential. Take the watermelon farm alone, wear nothing but an apron and keep on keeping on. Meanwhile, it’s important to mention that being an intimacy hound never excludes the astonishing impact of loving and being loved by other humans.

The rest of the year’s workshops happen, as most organized group action these days, on Zoom (or ZOM, as we like to call it). Brontez does three more, using some of the same writing and movement exercises that had blown his mind as a young person. Presaging each prompt with his statement on pedagogy—that he hates authority, so they should basically do what they want—he still loves watching the same synapses click for others. The teens, who, not big on names, affectionately christen him “that guy,” totally get Brontez’s whole thing. They repeat, over and over, “I really like that guy!”….“Just the whole way that he blew his nose and had us do those exercises, like, you could tell that he didn’t care if you liked him or not”….“He felt free!” We wonder about that as a group. How can someone feel free to others? In his last workshop, Auntie Brontez signs off with sincerely piercing eye contact (hard to do on Zoom) and says, “I love each and every one of you. Do not hesitate to be in touch!”

in your life?

in your life?