It is 1975, and a bisexual man addicted to heroin and a straight woman who works in the pornographic film industry are discussing the documentary they made about their marriage, the night they consummated that marriage, and their subsequent breakup on public access television. I discovered this wryly wrenching, charming film, The Continuing Story of Carel and Ferd, through its mention in Haley Mlotek’s striking new book No Fault, which also alerted me to the existence of a subgenre of mid-century self-help for wives (Help Your Husband Stay Alive!, How to Help Your Husband Get Ahead, Can This Marriage be Saved?), a menagerie of divorce movies, and a litany of obscure laws around the legalization of divorce.

Divorce, here, is a “topic made of endings,” a “genre,” and an “event,” not to mention an economic instrument, an impulse, an interpersonal crisis, a problem of punctuation as much as punctuality––I could go on. Mlotek’s hypnotic, slippery yet precise prose dips in and out of genres, gliding between memoir, film criticism, socio-political history, and philosophy to reveal the myriad meanings divorce carries in our culture. She is adamant about ambiguity, devoted to the revelatory potential of ambivalence as much as the pleasures of going all in, indulging in the “precipitous gullibility” that allows us to believe in a story, or fall in love. Last month, I called Mlotek at her home in Montreal to chat about paradox, The Ultimatum, marriage, talking too much, and Susan Sontag.

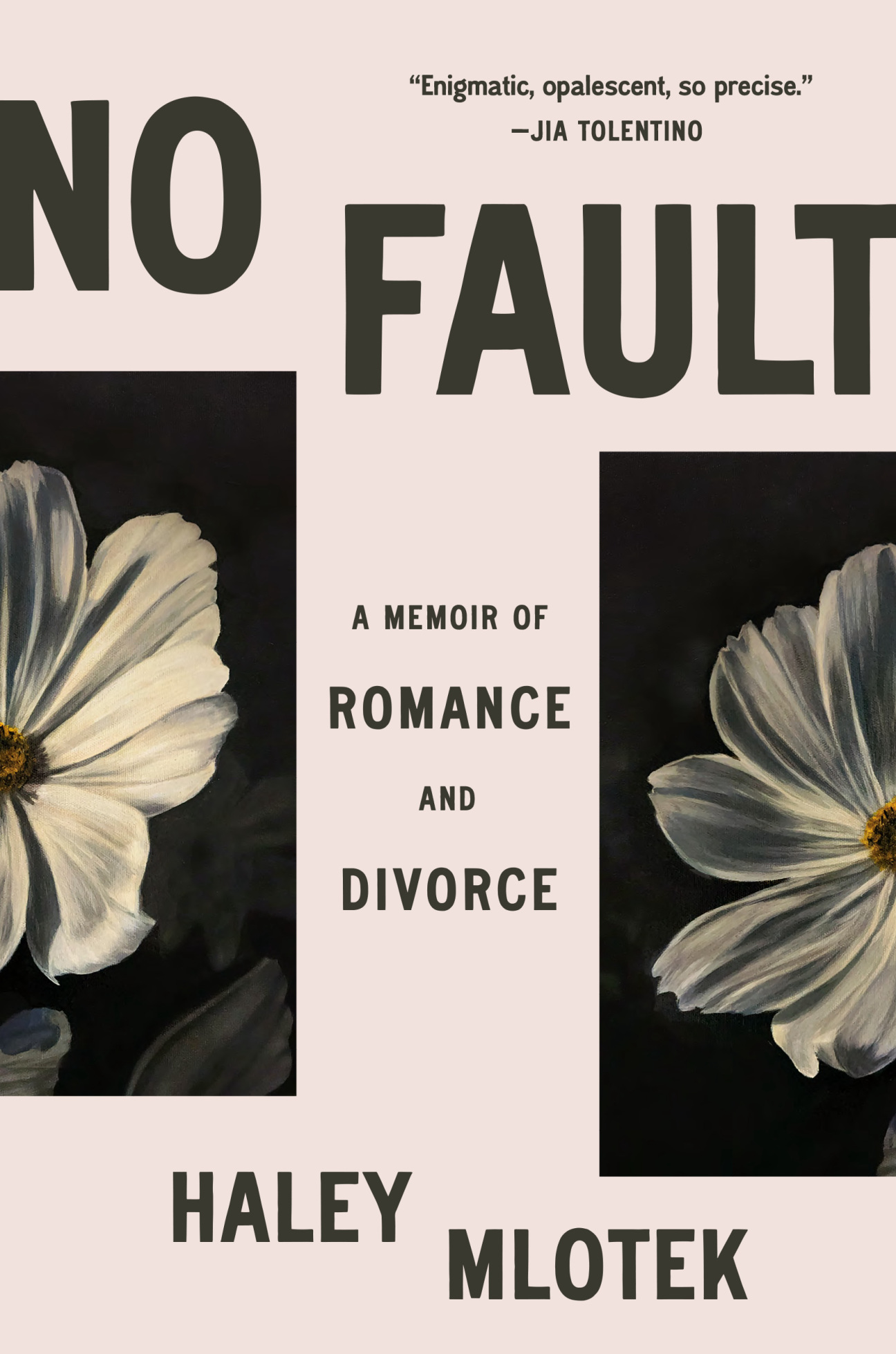

Emmeline Clein: This book is called No Fault, and it's subtitled “A Memoir of Romance and Divorce.” But it's so much more than a memoir. That’s not to denigrate memoir, which is, of course, constantly getting misogynistically vilified. But this project is almost uncategorizable from a genre perspective. You tell your own story, but you also narrate the legal, economic, and cultural history of divorce. Can you talk about your decision to take such a kaleidoscopic approach, as well as the decision to call it a memoir?

Haley Mlotek: I spent a lot of time describing the book as not a memoir, which is usually the first sign that I'm doing the opposite of what I say I'm doing. For many years, the project was an essay, and I would tell people it was not a book. So, that just goes to show a little about my process. But when I first started thinking of it as a book, I was very much inspired by an era of magazine writing that evolved from New Journalism. I was really lucky to take the original essay that became the book to a writer's residency directed by Susan Orlean. She is such a beautiful example of a journalist and essayist who always has her personal perspective very foregrounded in the writing in a way that lends it such grace, beauty, and authority. We had a workshop once where she said that the pleasure in reading is in the description. It's about seeing a writer put something that you recognize in their own words. And she was like, "Why are you all denying yourself that pleasure?" That went into the shaping of the book pretty deliberately, to make it something that could encompass all those elements. Because even in the sections that aren't memoir, obviously it's my decision what I include, it's my quite narrow perspective.

Clein: I always think about that when I’m bringing memoiristic prose into something more essayistic or argumentative. The impulse to take out the personal can actually dull a point rather than sharpen it––I don't know about you, but I live in a society, so I can only tell a reader my perspective from my specific point on the disturbing chutes and ladders board that is our society. I’m so interested in your comment about doing the opposite of what you said you were going to do. In the book, you observe that cynicism needs romance the way marriage needs divorce. That felt like a clear distillation of the book’s interest not just in looking at paradox, but in positing a political and aesthetic investment in paradox.

Mlotek: You know, that is maybe a good description of my principles, which are aesthetic and political in almost equal measure. I often find myself repeating very good advice I once got from an editor, which is “don't describe something by what it's not.” Because it is very easy to do, which is why I gravitate towards it in conversation. And the work of a writer is to not rely on negation or drawing the boundaries around something in a way that leaves the thing you’re looking at in the shadows. That is the thing that humbled me most about writing the book, because I am talking about something that's all about what it's not: It's a relationship that has changed form so drastically, it no longer has the same label it once did.

Clein: I was so intrigued by the role film and reality television criticism played in this project. I’m curious to hear how you chose the movies and shows you delved deepest into to tell this story, like the Carel and Ferd documentary and the reality TV shows.

Mlotek: I'm actually relatively new to watching reality TV. I only just started watching Real Housewives this year. All my friends had been screaming at me for years that the Housewives franchise is the number one cultural indicator of divorce in a very specific subcategory of people. But with the documentary, I came to it knowing that Gary Indiana was in the film. He's a quite minor character, but he had written very beautifully about Ferd Egan. It easily lent itself to a lot of research about where reality TV came from. I could write a whole other book about reality TV shows as union busting. And then, like many people, I am perversely fascinated by the Nick and Vanessa Lachey industrial complex that is taking over Netflix.

Clein: That was actually going to be my next question, because I do need your take on The Ultimatum of it all, if you have any thoughts.

Mlotek: Do I ever. Well, I was really pleased with myself for getting my favorite joke in, about how they treat marriage the way extreme adventure documentaries treat something like rock climbing without the proper harness. When we talk about compulsory heterosexuality, I don't think anybody could have seen that this would be its logical conclusion––the level of inevitability that they try to force on the people who are participating in the show, and the people watching it. Of course it is leading to the altar or to a breakup, something that is incredibly at odds with what we know about people's experiences. And that makes total sense to me in the same way that anything contradictory immediately makes sense to me.

Clein: I hate to use a highly overused word, but this book is ultimately written in what could be called fragments. The form lends itself really well to the chameleonic genre shifting you do, but I also know that it's sort of a risky time to write a fragment as a straight woman [laughs]. I was curious if you had any fears or anxieties around that.

Mlotek: I definitely did have some perhaps interesting internalized misogyny around fragments as a choice, which is something to discuss with a therapist and not in an interview [laughs]. There was a time when the literary fragment was definitely a pattern and then it became a trend. And then it did become something that you could expect, maybe, from a certain type of writer. At the same time, that's not the whole story. Sometimes—not always, but sometimes—things are popular because they serve a really good purpose.

Clein: This is one of my great passions. Things are called “basic” because a lot of people like them, and no one wants to admit to being like all the other girls, but that doesn’t mean those things can’t create pleasure or reveal something true.

Mlotek: I would never want to reject a tool just because of some preconceived idea about what it is or what it does. Actually, the thing that finally broke me out of the very traditional chapter structure that I was planning on was starting to work on a screenplay for the first time––learning the tool of the “cut to” in a script. As well as thinking about the influence that film has in literature and vice versa. I'm not going to compare myself to Susan Sontag–

Clein: You can compare yourself to Susan Sontag, this Zoom is a safe space.

Mlotek: I think about how seriously she took film, and you would never think about her as somebody who writes her essays or her books as fragments, but there is a sense of the jump cut.

Clein: I am also curious, on the topic of trends––there were a bunch of divorce novels and memoirs that came out this summer, and I would be intrigued to hear your thoughts on the critical micro-backlash that emerged in response to this subgenre.

Mlotek: It is interesting because once again, I feel very sensitive to labeling things. I do think there are cycles in the same way that we see trend pieces. A colleague of mine just posted in our Slack channel, “everyone's horny now,” and I think that sort of thing is so funny, because for years we were hearing, “nobody's horny anymore.” There's a cycle to what writers are thinking about and in the same way that writers and all types of artists have a great effect on the culture, the culture has a great effect on them. I often think about that Jean Rhys quote about how some writers are great lakes and other writers are little trickles, but everybody's some water feeding into the great body, and we can see that happening with divorce writing.

Clein: Speaking of influences, you mentioned in another interview that Barbara Ehrenreich’s writing was really formative for this project, especially the (holy) trinity of her books about the advice genre, bachelorhood, and wage labor. So I was hoping to hear you speak a bit more about how those books inflected your approach.

Mlotek: Yes, it is so wild to me that she's not directly cited in the book, which I do think is a sign of just how deep her influence has been in my life. I was lucky enough to interview her right at the beginning of the pandemic, and that was such a huge moment for me. It's not an exaggeration to say Nickel and Dimed changed my life. I found a copy of it at Value Village––I don't know what the American equivalent of that is––it's kind of like a Goodwill. I'd been working retail and as a receptionist, and I didn't know that you could write that way about work. She's having a good time, even slash especially when she's pissed off.

Clein: On the note of directly citing versus subterranean influences, this book engages with a lot of questions around disclosure, withholding, and secrets. You really interrogate what commitment means to conversation, and the way that coupledom can be a kind of communication enclosure. So I wanted to hear about your interest in existentially engaging with those questions, as well as the formal decisions you made around how much to literally communicate regarding your experience of being inside of a couple.

Mlotek: I do very briefly touch on this, but it's one of those little iceberg sentences where a bit peeks out, but there's a lot underneath. When I was first separated, I just didn't know what to say because the person I told everything to was no longer a part of my life in the same way. That was a very new experience for me and since then I have had other relationships and other breakups and I've seen how it's a function of that state of being in and out of coupledom, and it never gets any simpler. That is a big part of the subtext of the book, the sense of propriety and taboo that still surrounds marriages and divorce. On the one hand, like you were just talking about, there's this genre completely built on disclosures, but if you actually read a lot of the divorce memoirs, even some of the ones that are sometimes put under critical scrutiny for saying too much or being too unfair, what are they really saying? I think we all share a tendency towards the opaque. At the same time, [the subject] lends itself so well to voyeurism. Just yesterday, it was extremely funny, a friend just asked me directly, "Why did you get divorced?" And I was like, "I don't know."

Clein: Were you like, "Well, I did go ahead and write hundreds of pages trying to figure that one out, and they're coming to a store near you soon?"

Mlotek: I wouldn't tell anybody that they would get an answer in the book. You'll get something else.

Clein: When you're writing about dating after divorce, you observe that for a long time you didn't know what you wanted because you spent so much time thinking about what you could get. I thought that line was a total gut punch. It also felt really related to some of Ehrenreich’s writing at the intersection of feminism and economics.

Mlotek: When I was writing the book, the other major thing I was working on was organizing freelance writers for the National Writers Union, and people would always lovingly tease me because we had these meetings where I would give the same speech to new members every time. I would always talk about fighting the scarcity mentality as freelancers. That influenced the way I looked at everything, but certainly the way I looked at love and companionship and marriage and divorce. As you say, women, and to a certain extent anybody of any gender, are susceptible to these myths that you should be so lucky to find somebody who can basically stand you. It's a very new fear that you might be with somebody who is good enough but not your person. And that can be very destructive, or it can be very illuminating. It can encourage people to keep their standards very high, which they should, and it can also encourage people to treat others like they're disposable, or reinforce the market logic.

Clein: Another moment in which I felt both personally attacked and––trigger warning for cringe––seen, was when you said that sharing too much is an excellent substitute for thinking enough. I was curious how that maxim functioned as you were writing.

Mlotek: Anytime I make a big sweeping statement about the way things are in the book, I'm just talking about myself. That is just a funny joke that I'm playing on everybody. But I've always found that when writers do that, those sentences are the ones that make me go, Why are you attacking me personally slash thank you so much. That sentence, I hope, is one of those, because there was definitely a phase after I was divorced when I felt like people were really prying, and they wanted something out of me that I could provide, but I found the experience to be very hollow. That led to me deciding to keep a lot to myself until I know what it is I have to say.

in your life?

in your life?