It's roundup season.

Because your inbox is likely flooded with lists of the year’s best novels, nonfiction tomes, "romantasy stories to cozy up with," and "bingeable television shows," I thought I’d try a different tack.

This year saw more than a few literary dustups, both in old-fashioned print media and, of course, on X fka Twitter—everyone’s favorite platform for fervent, nuance-free feuding. I've attempted to round up 2024’s emblematic literary controversies, from a wife guy going after a gay guy via tweet screed to Rooney-galley-gate. You may find some holes; I couldn’t cover everything. After all, in the realm of gossip, much is better discussed over drinks than in writing––so consider this an amuse-bouche, and whisper about what I missed.

Below, discover this year’s best books along the axes of discourse and gossip.

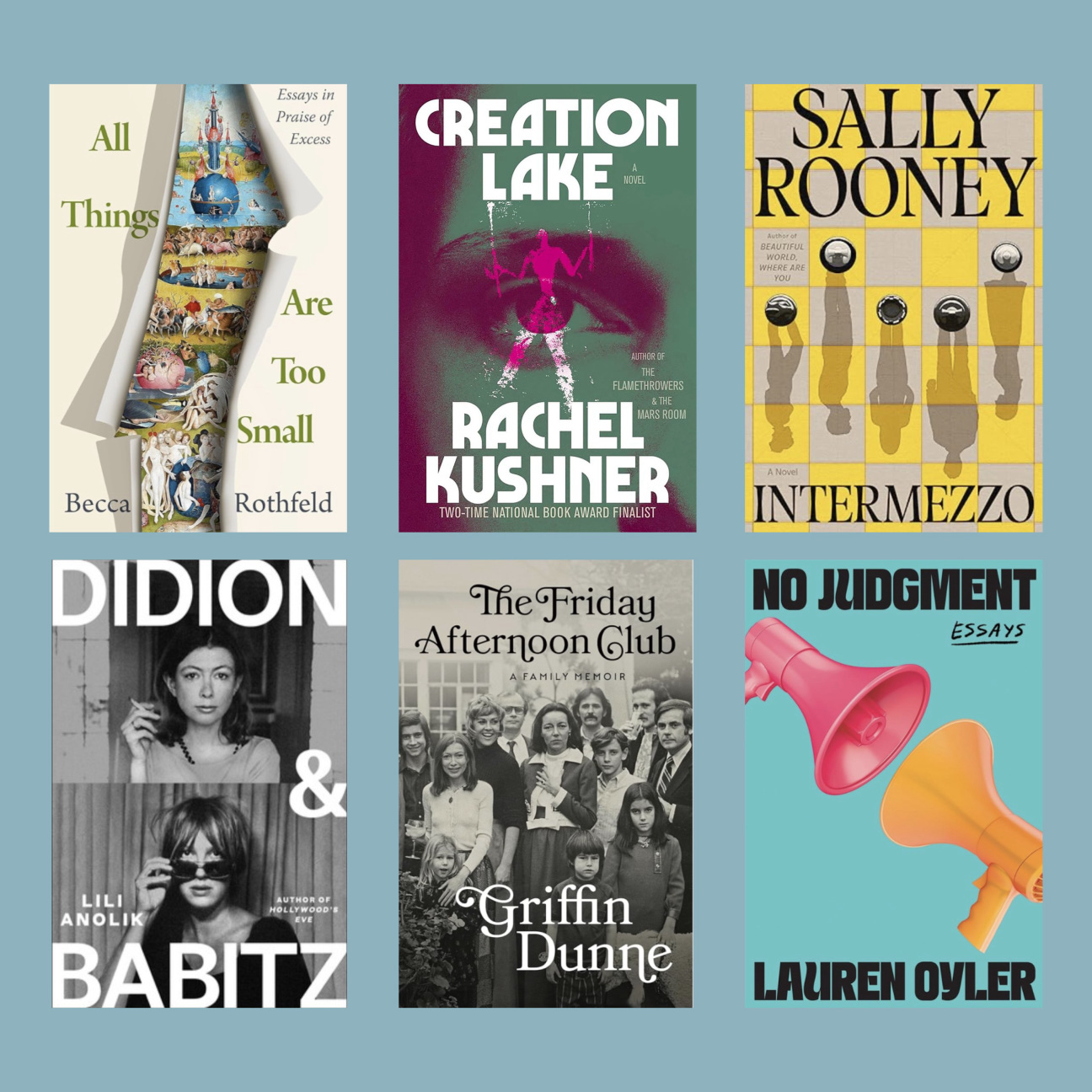

1. Sally Rooney, Intermezzo

Before Rooney’s latest novel—an experiment in using Joyce-inspired narration to advertise throuples and age gap relationships—was even published, Esquire was salivating over the galley-bragging frenzy incited by the book. Rooney’s publisher personally inscribed and numbered every galley, rendering an ARC “the summer’s latest must-have for the literary It girl.” The book was released to mostly positive reviews—even from notorious takedown artist Andrea Long Chu, whose colleagues at New York Magazine courageously asked the question most critics refused to engage with: What, possibly, could Sylvia’s mysterious sexless martyrdom-inducing condition be? Over at Vogue, Emma Specter noted that Rooney is addicted to writing women waifs whose jutting bones turn her male characters on, and then into awe-struck aspiring saviors. Perhaps Leah Abrams put it most succinctly in AirMail’s roundup of sound bites on the novel: “Another Rooney book where quiet, nobly suffering women are cured by magical dick.”

2 & 3. Lili Anolik, Didion & Babitz, and Griffin Dunne, Friday Afternoon Club

“Could you write what you write if you weren’t so tiny, Joan?” That banger of an Eve Babitz line appears just pages into Didion & Babitz, Lili Anolik’s exploration of the friendship, mentorship, rivalry, and rusted-over love between two of the last century’s most ingenious, incisive women writers, who our current century has successfully reduced to tote bag and Instagram fodder. The book is worth reading for the excerpts of Babitz’s unsent letters alone (instructions from Babitz to an ex-boyfriend included the line “leave bohemian c*nts like me to their own destruction”).

Anolik’s expansive research offers surprising insights into Didion’s marriage. The author posits that Didion’s husband was prone to affairs with men, and that the real love of her life was a hard-drinking Southern journalist who handpicked his own romantic successor. There is some unforgettable scene reporting on ’70s LA: One restaurant frequented by Babitz is described by a former patron as “the kind of place where you were always running into people you’d last seen in Tangier.” It also includes one of the most memorable footnotes I’ve ever read, in which a drunk and despondent Elvis is sitting on the floor of his Vegas hotel suite, debating whether to let his jet land––he was fighting with the girl inside it, and wasn’t ready to let her out of the sky.

Since we’re already loitering inside the Joan Didion industrial complex, I’ll add one more frothy, salacious-yet-sweet addition to the canon, from Didion’s nephew-by-marriage Griffin Dunne. Filled with star-studded anecdotes plucked from its author’s youth (Tennessee Williams copped a feel at a party, Sean Connery saved him from drowning, his best friend Carrie Fisher tried to lose her virginity to him), Dunne’s memoir The Friday Afternoon Club recounts his upbringing in a bygone Hollywood. He writes with wrenching elegance and disarming humor of his sister Dominique’s murder and the subsequent criminal trial chronicled by his father, a down-on-his-luck producer who became a controversial crime writer in the wake of her death.

4 & 5. Lauren Oyler, No Judgment, Becca Rothfeld, All Things Are Too Small

Lauren Oyler, who has (iconically) admitted in print to getting drunk at parties and calling herself “the preeminent, mostly widely read critic of my generation,” originally titled her essay collection Who Cares, a question that could also be asked about the girl-on-girl warfare sparked by the book’s release. No Judgment came out to mixed reviews, some of which were overtly misogynistic and others which were unjustly accused of the same.

As Oyler pointed out on X, the Guardian went straight to the sexism store, calling her “bossy” and accusing her of lying about her appearance. Meanwhile in Bookforum, Ann Manov made the incisive observation that much of Oyler’s “research” consisted of cursory Google and Wikipedia searches and compared the collection to a “juvenile burn book.” Intelligent takedowns by Manov and Becca Rothfeld (in the Washington Post) spawned a snowball of accusations that Oyler was being "woman’d" (a term coined previously by Rayne Fisher-Quann to describe the phenomenon in which “mass public opinion on a woman reverses dramatically, universally, and seemingly overnight.” (Fisher-Quann clearly stipulates that is “not the same as being criticized”). In response to the frenzied reaction to her and Manov’s criticism, Rothfeld pointed out on her Substack that it is possible for a woman to identify flaws in another woman’s work for reasons other than jealousy or cattiness, bravely asking her readers: “What if someone can disagree with you without being stupid?”

Rothfeld also released a book this year—a brilliantly bizarre, expansive critical collection entitled All Things Are Too Small. Covering everything from the harrowing experience of waiting for a text to the work of Simone Weil, Marcel Proust, and John Rawls, the collection also includes a scathing assessment of the recent turn toward fragmentary, anti-plot novels. Rothfeld’s characterization of her romantic and erotic life inspired one reviewer to assume she was in an open marriage and use that fact as the basis of her criticism of the book—frankly, a weird and invasive approach to literary analysis. It was also incorrect, prompting Rothfeld to respond with a Substack post (aptly titled “my marriage is not open”) that deconstructed the review’s misreading of her life, and her actual point about the transformative possibilities of sex and love.

6. Rachel Kushner, Creation Lake

Rachel Kushner’s fourth novel follows a disaffected (and hot) Ph.D student-turned-spy as she insinuates herself into a radical farming commune in rural France in order to foil suspected eco-terrorism plots. Brandon Taylor––author of two novels and a collection of short stories, and an expert poster specializing in cutting, witty tweets––panned the otherwise well-reviewed, National Book Award-longlisted and Booker-shortlisted novel in a withering takedown for the London Review of Books, boldly titled "Use Your Human Mind." Taylor’s review, which included lines like “I couldn’t decide if the book was a smart person’s idea of a stupid book or a stupid person’s idea of a smart book” and “as I read, I kept wondering, why did you even write this?” inspired a rash of online arguments, and even prompted Kushner’s husband to take to X, personally haranguing Taylor in defense of his wife and setting off various online sub-feuds. All these tweets, (not to mention Taylor’s entire X account) are now lost to the ether. If anyone has screenshots, please send them my way.

in your life?

in your life?