Adam Eli: Can you each describe a little bit about your practice and how you got involved with the book?

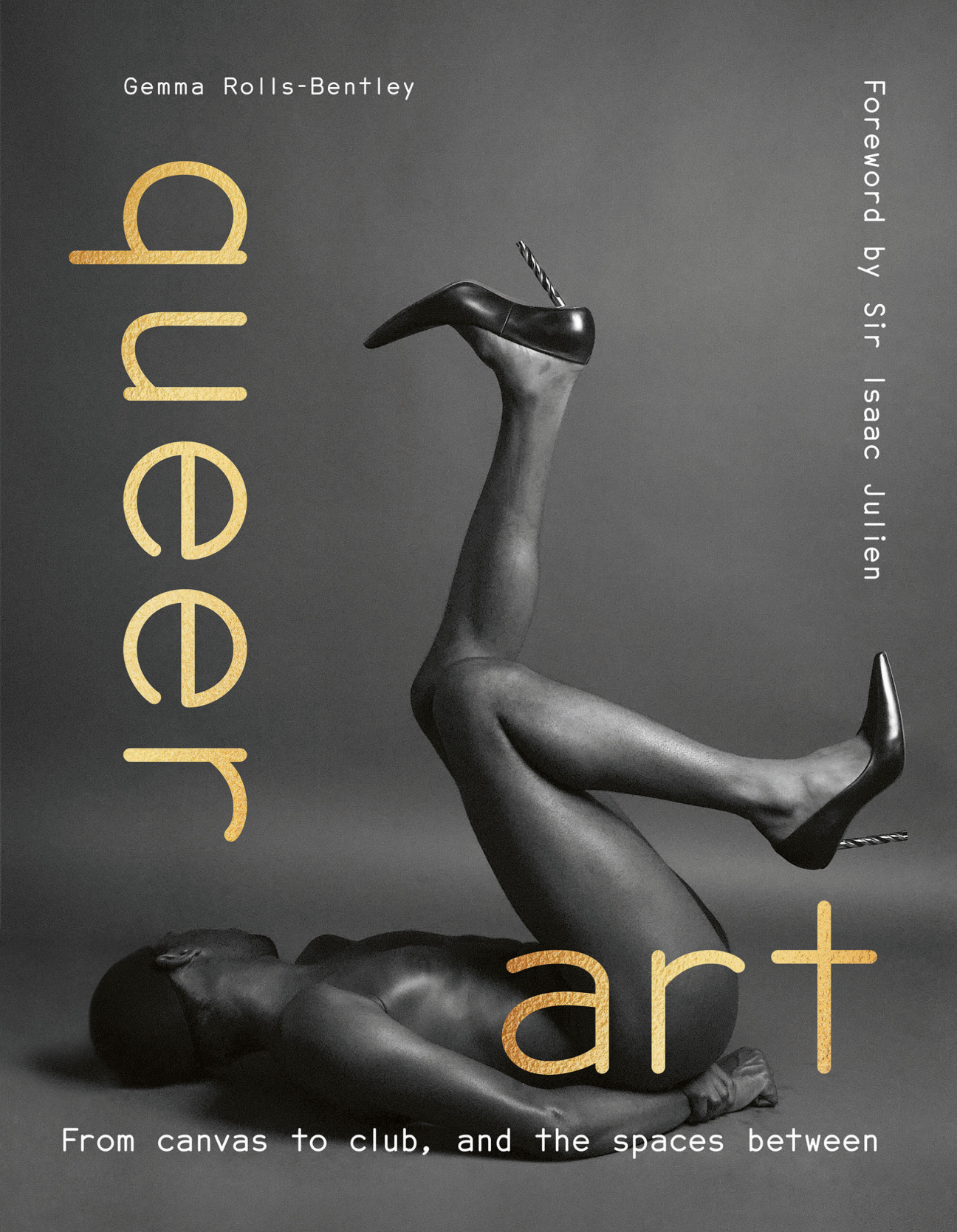

Gemma Rolls-Bentley: I am a curator, a writer, and a consultant. I wrote this book because over the last decade, my curatorial practices tended to focus on working with queer artists. As a result, I get people asking me, “Is there a good queer art book?” There have been some brilliant books, and I referred to some of them while I was writing this one.

My favorite is Lesbian Art in America that Harmony Hammond did in '93. There is also the Phaidon book Art and Queer Culture that came out just over 10 years ago. However, I wanted to make a book that felt super accessible—for the community, but also for anybody outside of the community to get an insight into our world. These two amazing artists very kindly agreed to be part of the book.

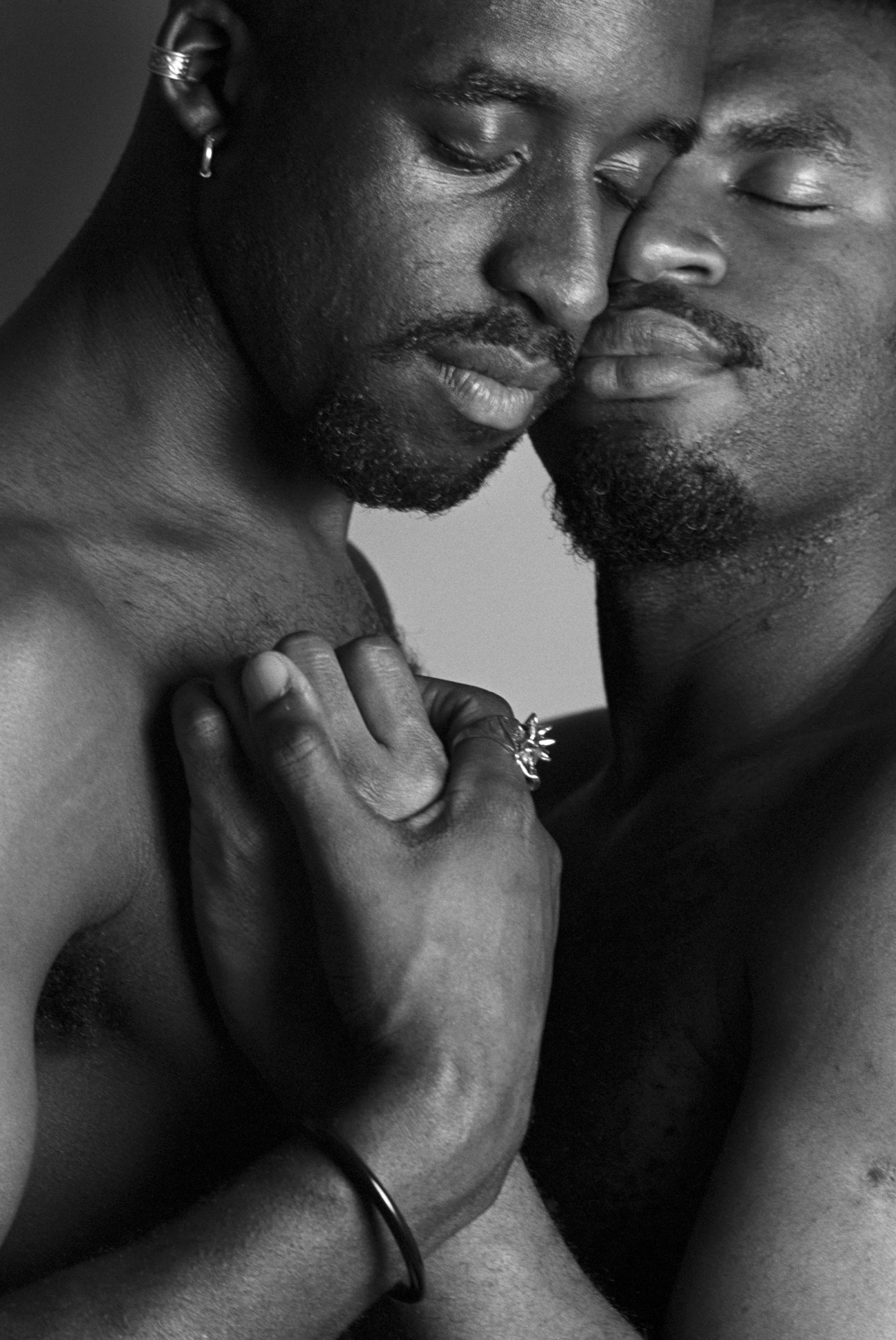

Ajamu X: I'm a fine art photographic artist. A lot of my work is about playing with and against ideas around the erotic, pleasure, and joy. There are a lot of questions I don't think get asked or that get sidestepped around the Black queer body. I love the book, and I'm glad that there's a Black body on the front cover. I'm glad it's not a muscular Black body, but a very feminine Black body. I'm glad that it's a sexy image, because I think that queer culture doesn't do sex very well. I think it does sexuality well, but I don't think it does sex very well.

Over the years, we've had some wonderful books around queer art and Black artwork, the production values have not always been fantastic. This is a beautiful object. That's what I love about it: it's an object, not just a book.

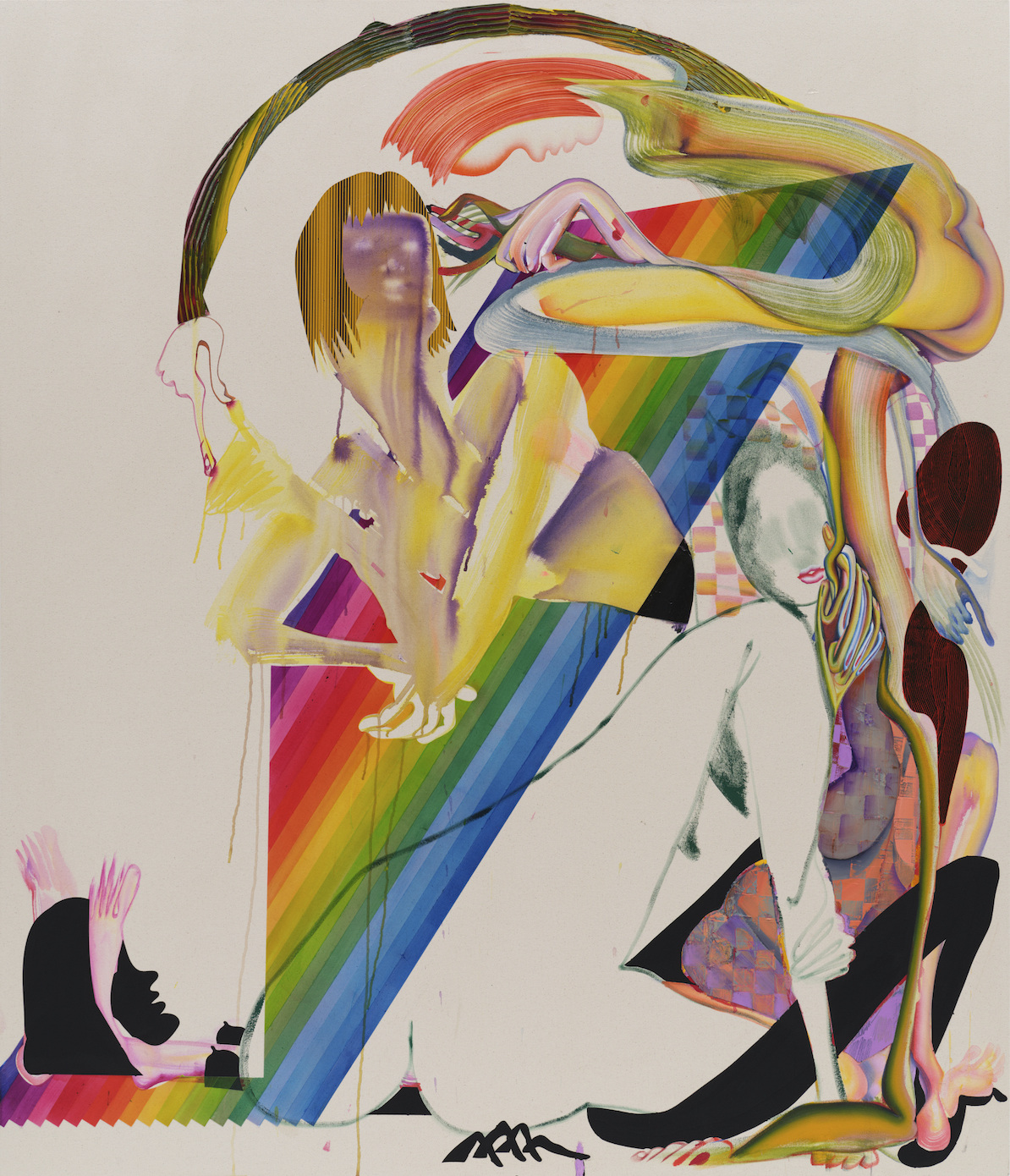

TM Davy: I was introduced to the book through Gemma, who I met in the queertopia of Fire Island. We met through mutual friends, Joe McShea and Edgar Mosa, whose work, also about Fire Island, is on the page opposite mine. Fire Island was a place where I found the permission to be my fully fairy-loving self.

The book is truly stunning. The narrative is woven to tell a very large story of what is a very tightly knit community, a community that is expanding through this book and beyond this moment.

Eli: Why are books like this important? What purpose does a queer anthology serve?

X: What I love about the book is that it complicates the very idea of queer. A book like this serves to show the diversity of queer artistic practices. Usually, we are stuck with one or two named queer artists, and they're usually white.

I still get excited when I see my work in print. I love exhibitions, but there's something about a book, because when I was younger, books were my escape from a small town. I'm sure that lots of younger queer artists will find this book as a way to escape in all kinds of ways as well.

Rolls-Bentley: I really wanted the book to communicate how multifaceted the queer experience is. I wanted that diversity to play out in terms of artist identity and career stage, how we measure success, and where you might find an artist's work. There's a large number of artists in the book who died of AIDS, and I feel that we must do anything we can to maintain and build their legacies.

There are some artists that you may not have heard of because they've maybe not been in a museum or a gallery. There are other artists who loads of people have heard of because they're on Instagram, but maybe they've not been in a gallery. I've got a couple of video game artists and NFT artists because I wanted that diversity to play out in terms of medium as well.

Davy: A healthy ecosystem is splendidly diverse. It's not about knowing everybody, but the belief that we're all deeply interconnected. [There is a] feeling of belonging when I meet really any queer artist, because I know that we're part of some kind of dream that we're all sharing, a kind of garden. To see that I made it into this gardening book for queer artists that explains how things are growing—it's just thrilling.

Eli: TM, I want to come back to what you said about Fire Island. The book speaks a lot about space, both literal and theoretical, and the impact space has on the art, the artist, and the queer movement. What type of space do you need to make what you're making?

Davy: Well, when I make big paintings, I need a studio. Luckily, I have one at the workspace in Bushwick that is not too far from Fire Island, where my husband is an ecosystem-conscious gardener. This summer, I have a dream that I'll make smaller paintings because I really love feeling like I'm free to begin an artwork wherever I'm at.

For a while, I was doing pastel gouache works on paper—that defined a few years of my art practice because I was so inspired being around all these artists on Fire Island. I had a sort of transcendental ritual of painting the sunset, until I had to stop because I thought I was burning my eyes out.

X: I work in my studio and the darkroom. The studio is my laboratory where I work out ideas, draw upon my lived experiences, my sexual experiences. The studio is my play space.

For me, it is safer to try and get the images out of my internal space into a physical space. The worst form of censorship is actually self-censorship from Black or queer artists. I also come out of that post-punk moment and a lot of my work draws upon that energy from when I was a teenager. I'm all about creating brave spaces and not necessarily safe spaces.

The reality is there've been lots of challenges over the decades, especially around the work that is or was very sexual. Anyone wanting to work around the erotic will have challenges, certainly in the context of the U.K. How do I maintain it all? I have thick skin.

Eli: TM, I see you nodding. It seems like the idea of creating brave spaces instead of safe spaces resonates with you?

Davy: Growth's edge is a risk—to reach a little bit further into what feels like life. I'm really enjoying being alone in the studio these days, but I'm not censoring myself anymore. I feel like I can allow myself to feel safe enough to make something that's super personal. It's like you're extending yourself forward into a kind of unknown, hoping that life is there.

I know that I need certain conditions to feel safe enough to reach that place. For me, getting to that place is rooted in all of the artists who are included in this book who have died of AIDS, who were brave enough to say what it feels like to be a queer artist when it was far less safe than it is now. That bravery created a condition in my nervous system to trust myself and [for] my community to love me. That trust enables me to make work.

X: Sometimes we get so locked into the identity around being queer creatives. And sometimes I don't have the courage just to surrender to the process. There might be times I've gone into the studio with an idea, but by the end of the session, I've ended up somewhere differently in the composition, the idea, the lighting. That's what I love about being in my studio.

Rolls-Bentley: I believe very strongly that artists should not ever be pigeonholed because of their identity, which I think to some people seems counterintuitive because I work so much with queer artists. But the title of the book, Queer Art, is just one of the lenses through which we can look at an artist's practice. It should never be a reductive process. It should be an enriching process.

I did two art history degrees, and nobody ever mentioned queer art to me. During that time, I was really struggling to figure out who I was, make sense of myself and my identity within that Northern British English context [that Ajamu and I share]. I know that if I had had this cultural dialogue to turn to, I would have found that period of my life a lot easier.

That's not to say that we didn't look at queer artists in my art history studies. We looked at loads of them—they just weren't presented as queer artists. I very deliberately put in this book artists like David Hockney, who is pretty much a household name. But how often are people talking about his queerness? His work is explicitly queer. In 1966, he was literally making a series of etchings of two boys in bed together.

I put Francis Bacon in here—the series of works he made after his lover, George Dyer, died. Again, explicitly queerly romantic. I think it’s interesting for people to realize that those big figures are also queer. They've always been there, and it's just one of the ways that we can look at their work. It's never going to be the only way. And it should never be the only way.

Eli: I want to push back on that a bit, Gemma. David Hockney is a very extreme example as he is firmly part of the Western canon. A lot of the other artists in the book, especially the earlier career artists, may have always and only been seen as queer artists. How does being placed in queer anthology impact them? How can being labeled as a queer artist be helpful or hurtful?

Rolls-Bentley: This is a great question and it's something that a lot of artists I work with think about often. How much should they lean into that label of queer art? What is the risk of being pigeonholed? I would never do an exhibition of artists grouped just because of their queerness.

It must have some kind of nuanced dialogue around the parts of queerness that they're discussing or other parallels or conversation points within their practice, whether that's about the work itself and the formal qualities or the subjects that they're dealing with. The last show I did, which was working with LGBTQIA+ artists, was called “Dreaming of Home” and it was about what home means to us as queer artists, whether that's finding a safe place to live, migration, feeling at home in your own body, etc.

So this book, whilst it's offered as an introductory read of queer art, is organized into three acts: queer spaces, queer bodies, queer power. Within each act, there are thematic chapters like visibility, home, love, [and] queertopia, so that people can do a bit of that work to think beyond the queerness.

There is so much benefit to looking through the lens of queerness because of the opportunity to see ourselves reflected, to share our experiences with the wider world. But I think it needs to be done in a responsible way. That is the responsibility of curators or people like me who are working with artists to make sure that you are having a sophisticated conversation. The same has happened with Black artists, artists of color, women artists, etc.

X: The bigger question is, who's doing the pigeonholing? As a queer artist, at certain points in my practice, it was useful to use words like “masculinity” and “queer” and so on. Because if I'm searching for doors that open around certain kinds of identities or ideas, then using the words can be strategic.

Queer artists, Black artists, trans artists have always had to deal with these complexities. It is part of what it means to be an artist. We are still in a place where lots of artists—Black, queer, or trans—still do not get looked at all. Sometimes it's useful to use this language as there's still lots of challenges for queer artists.

Davy: It's not a duality of human artists versus queer artists. To say that you're engaging in a queer art is to say we're all seeking to understand this human condition, and art's role—if there is a role other than to just let human beings be free—is to chart a course into freedom and expand it. To be queer is to say, “I don't think that this has been charted quite in the way that I feel it.” It's just the person on an exploration of what it is to be alive.

Eli: Part of the brilliance of the book is that it's not presented linearly. What lineage are you looking to situate yourself in? What lineage do you want to create for the future? In other words, who are you making art for?

X: First and foremost, I'm making art for myself. The audience is second to that. In terms of lineage, a lot of that is just not up to me. I just have to make the work and then have the kind of dialogues I want to have. The future stuff will take care of itself.

Davy: I don't believe in time. On a certain level, I'm singing with Sappho. I'm remembering the first person who told the story that the mother of the people was a fairy. I imagine that person was queer. I just think we're in a great mystery. When you get to the art with a capital A, which I think is what the book is about, it sort of bounds beyond time, which is why the timeline isn't really the interesting part.