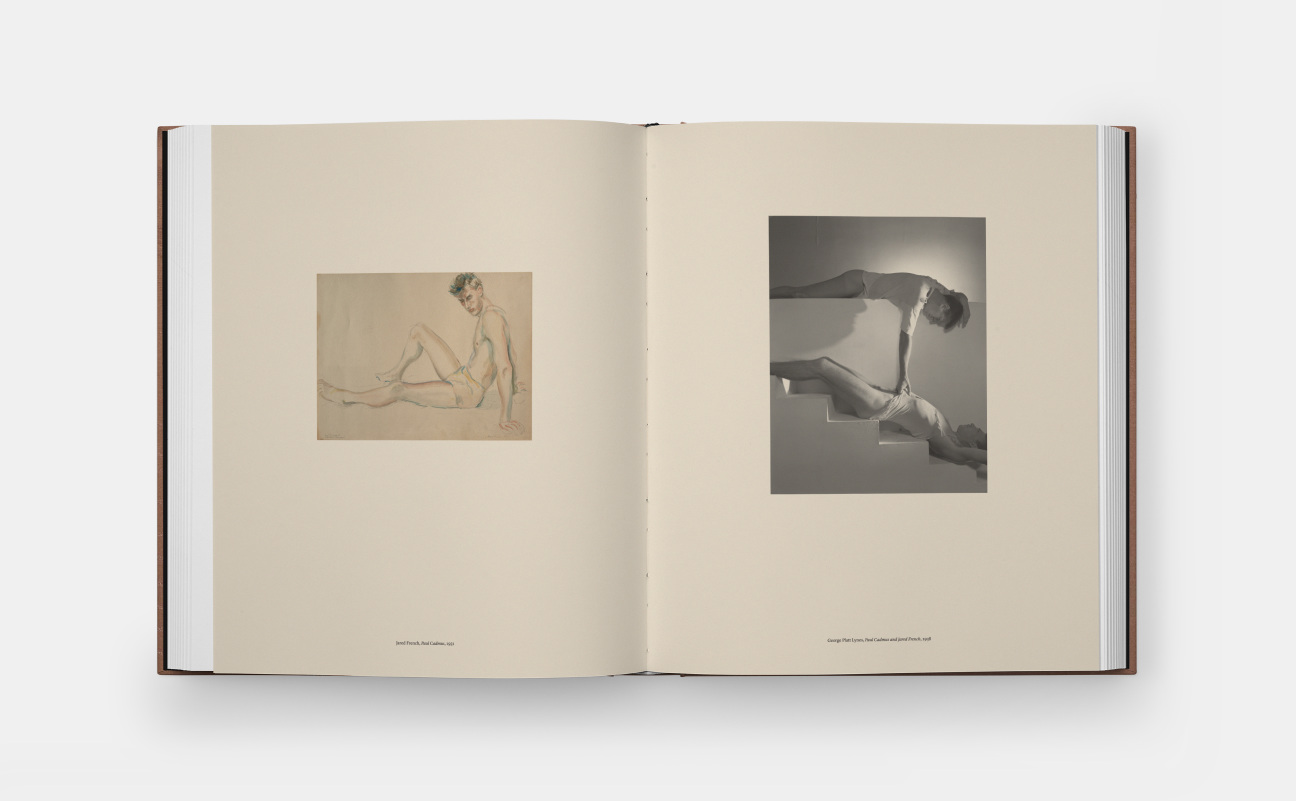

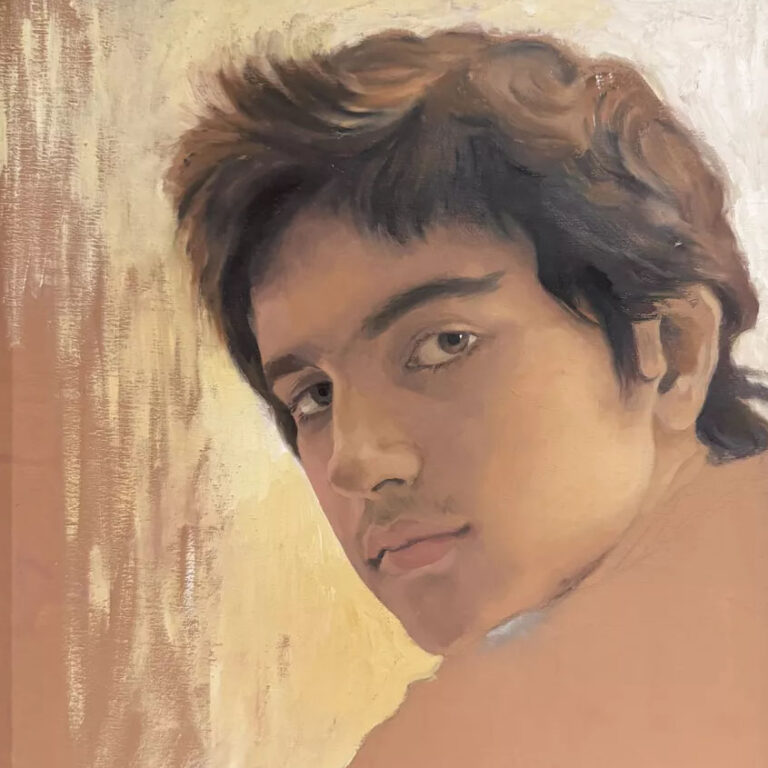

At the time of his death, artist Paul Cadmus had 49 chalk drawings of his lover stashed in his personal effects. Erotic, highly detailed, and prolific, the drawings are a testament to the obsessive nature of love, and the private queer relationships of the 20th century.

A controversial painter in his time, Cadmus’s mastery of the form has long been largely undervalued. This November, Monacelli Press, Hauser & Wirth, and collector Graham Steele are out to change that. Paul Cadmus: 49 Drawings is out today and features the previously unseen portraits sold at auction by Cadmus's partner, Jon Anderson, and later passed on to Steele. The publication is supplemented with over 100 additional illustrations and a envelope closure meant to ensure the lasting privacy of Cadmus's work.

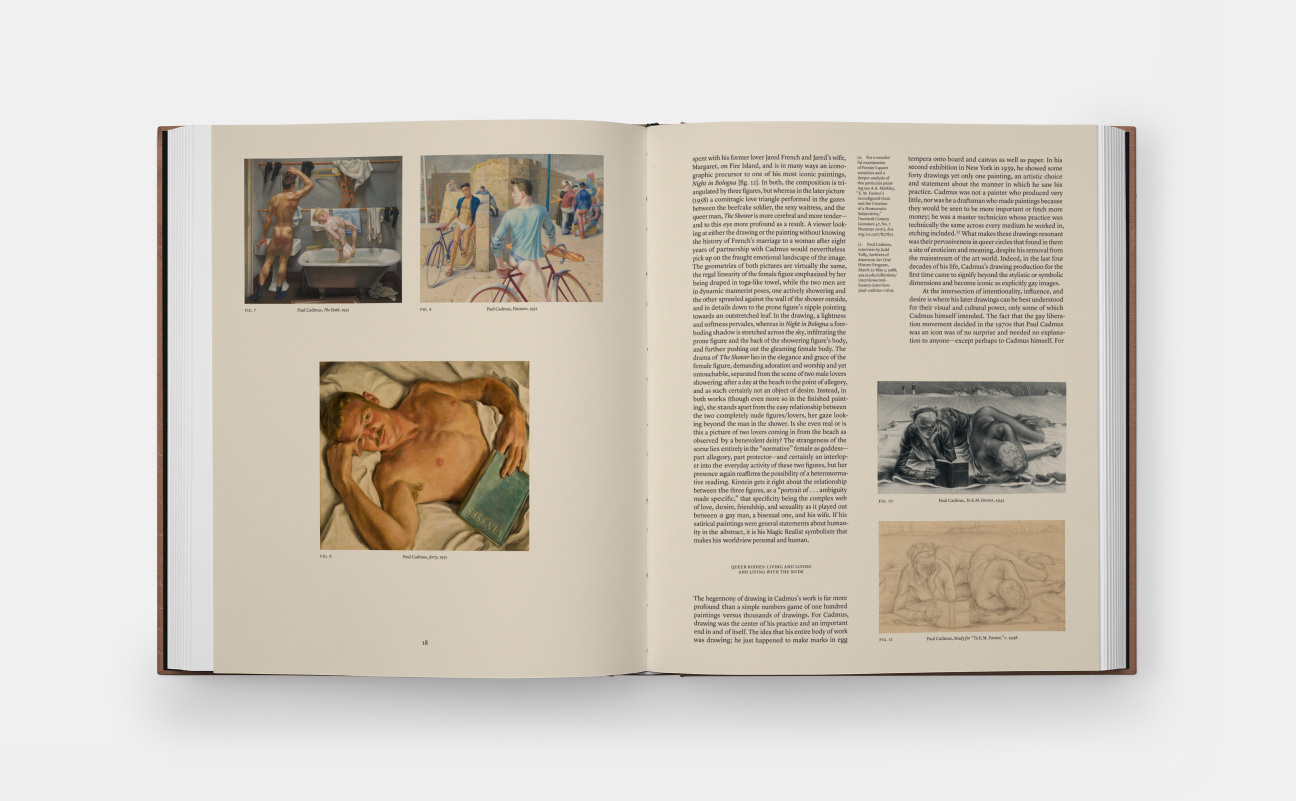

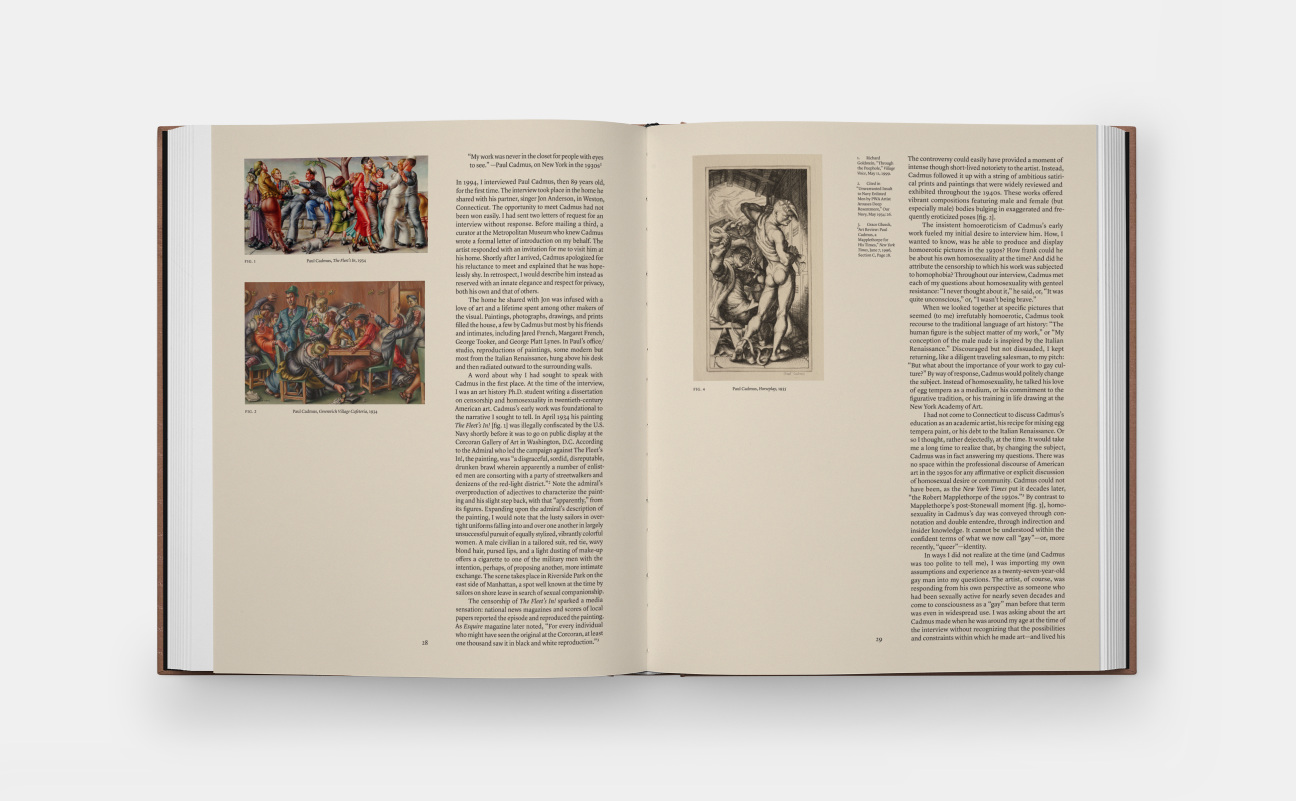

It is the only publication of the painter's work presently in print and includes a roundtable discussion featuring artists Nash Glynn, Oscar yi Hou, and Doron Langberg, moderated by writer-curator Jarrett Earnest, as well as an essay by queer art historian Richard Meyer, who interviewed Cadmus during his lifetime. Below, Steele reveals how the previously unknown works came into his possession, and why it is so essential that they now see the light of day.

CULTURED: How did you first become aware of Paul Cadmus's work?

Graham Steele: I first saw Cadmus’s work when I was a kid growing up next to Dartmouth College. The Hood museum there has a wonderful painting called Francisco, a portrait of a factory worker Cadmus and his boyfriend painted in Mallorca in 1933. They also have one of five drawings he did for the work. It’s hard to describe what I felt when I saw it, other than that it left a deep impression on me before I could even begin to admit what I was. I just knew I loved it.

CULTURED: Can you tell us about the process of acquiring these works?

Steele: Cadmus lived to be 95, and outlived almost all of his famous friends and lovers. As such, he became the repository of a great wealth of art, letters, and ephemera of a whole group gay and queer artists from his circle as well as his own work. His last lover, Jon Anderson, inherited all of this upon Cadmus’s passing and during the pandemic, after his own death, the entire estate was, somewhat tragically, sold at an online auction by a very small auction company. What makes the set in the book so special and makes me think it was all kismet was that they were the only works Paul never really intended for anyone to see and also the only grouping of works that Jon sold. He sold them to a queer collector and dealer who I know and who entrusted them to me. The idea to make a book about them, that went beyond merely making them public, just made so much sense.

CULTURED: How will this publication expand our understanding of the artist?

Steele: There is nothing in print currently about Cadmus and at resellers his books average about $200, which means younger scholars and gay and queer kids at their local libraries trying to figure themselves out like I did would have trouble finding out about him. Furthermore, none of the publications really talk about his sexuality as an important factor in his work or his life. This publication opens a door through these 49 drawings to more scholarship and appreciation of his entire body of art as a gay man in what would become a more openly queer landscape.

CULTURED: How do you see Cadmus's work, and these pieces, fitting into the larger queer canon?

Steele: What strikes me as a self-described failed art historian is that in the art world we often have amnesia about the past. We are celebrating queer visibility (and rightly so) but we often do so without a full understanding of previous generations’ contributions to that viability. Cadmus was one of the most exhibited artist for decades at the Whitney Annual Exhibition and Biennial, and remains constantly on view there. Yet the fact that he shot to fame for putting a transgender person cavorting with drunken sailors, in a painting made for the government, remains somehow unknown for new generations. He is the American disruptor of the pre-war years, and hopefully this publication incites more study of all periods of his production. The conversation between Doron, Nash, and Oscar with Jarret was really an interesting start to that.

CULTURED: When you first looked through these intimate works, what do you feel you were able to learn about Cadmus?

Steele: These images are so tender, and document decades of close study, albeit almost passive study. This particular ass, this one set of balls—something any long term partnered person knows of their spouse like they know their own body—was lovingly captured over and over again during their time together. There is the awe of discovery and the comfort of long intimacy in these drawings, and yet they feel like Old Master studies as well. They are in a way a lens through which to see Cadmus’s work: classically flawless and urgently contemporary.

in your life?

in your life?