The first book I read by Orhan Pamuk was My Name is Red. It was New Year's Eve when I first picked it up. I was in California visiting my mom, who was going to my uncle’s house for the evening. I was supposed to join her, but instead, I just stayed in and read, absorbing in the world Pamuk had created. After that, I read every book of his I could get my hands on.

Pamuk sees the world like a painter, which makes sense given his background. A painter, after all, takes the time to study their subject, to break it apart and put it back together, layer by layer. Pamuk’s way of writing felt like that to me—always observing, always questioning, always rearranging things until they made sense in a new way. His writing captures a mix of ideas, emotions, and history that resonates with me deeply.

In 2014, I was in Paris for a few days, and my art dealer, Thaddaeus Ropac, invited me to a dinner. He mentioned it would be a small group of friends, but didn’t tell me exactly who would be there. When I arrived, I found myself seated between Anselm Kiefer (an artist I had admired for years) and Orhan Pamuk.

My next encounter with Pamuk came in February 2020, just before the world shut down, at the Morgan Library in New York. It was an odd coincidence—both of us happened to be at the same exhibit on the visionary architect Jean-Jacques Lequeu. The museum was almost empty, and it felt like a private moment, just the two of us wandering through the galleries. It was the last exhibition I attended before everything went into lockdown—a memory that feels strangely significant.

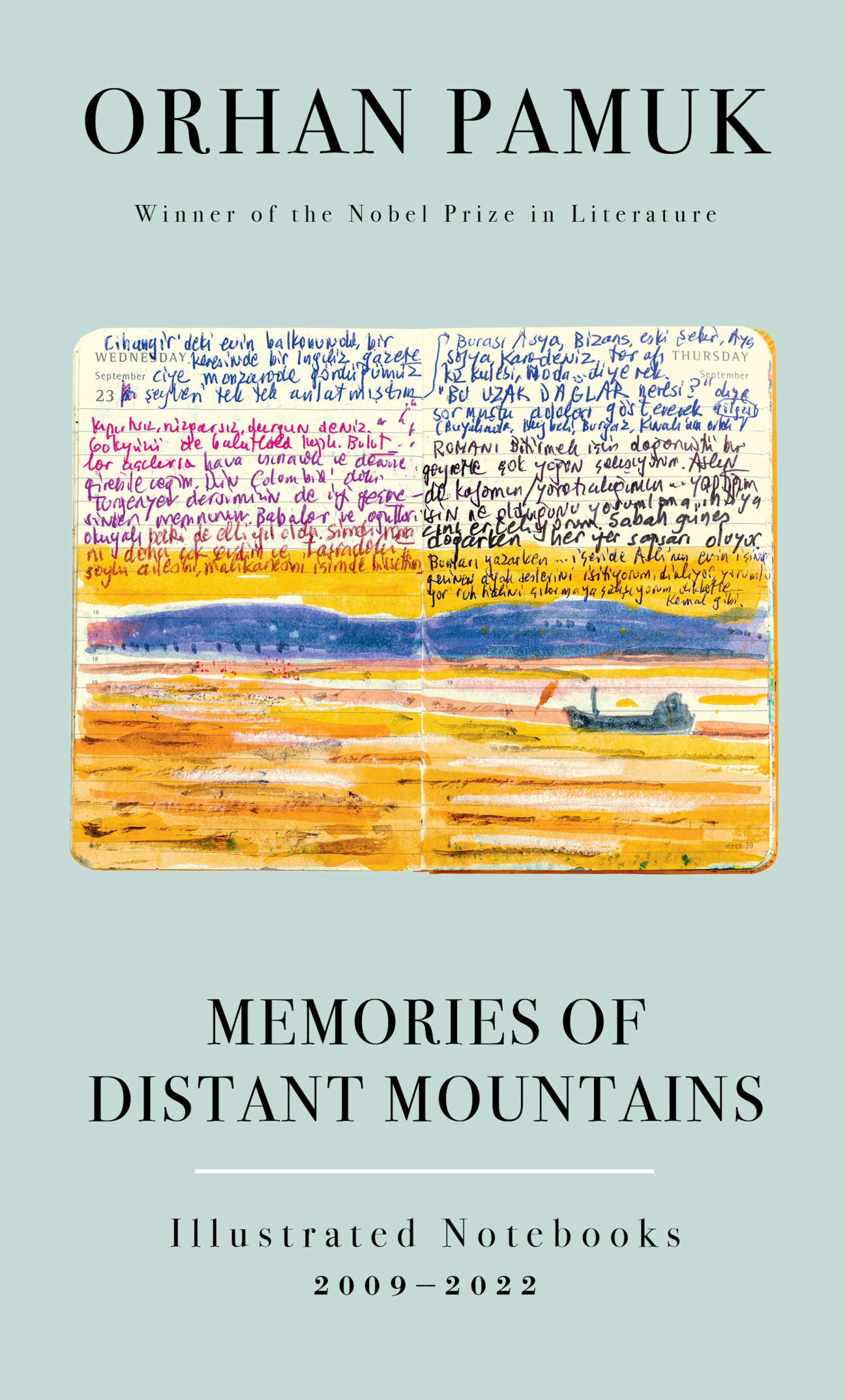

So it is with great pleasure that I spoke with Pamuk once more, this time on the occasion of the publication of his new book, Memories of Distant Mountains: Illustrated Notebooks, 2009-2022.

Ali Banisadr: I got your book last week, and it took me back to one of my favorite journals of Delacroix.

Orhan Pamuk: Wow, yes. I wrote about him. He’s very hard-working, very serious, but he doesn't have a sense of humor. You can sense that he is very authoritarian.

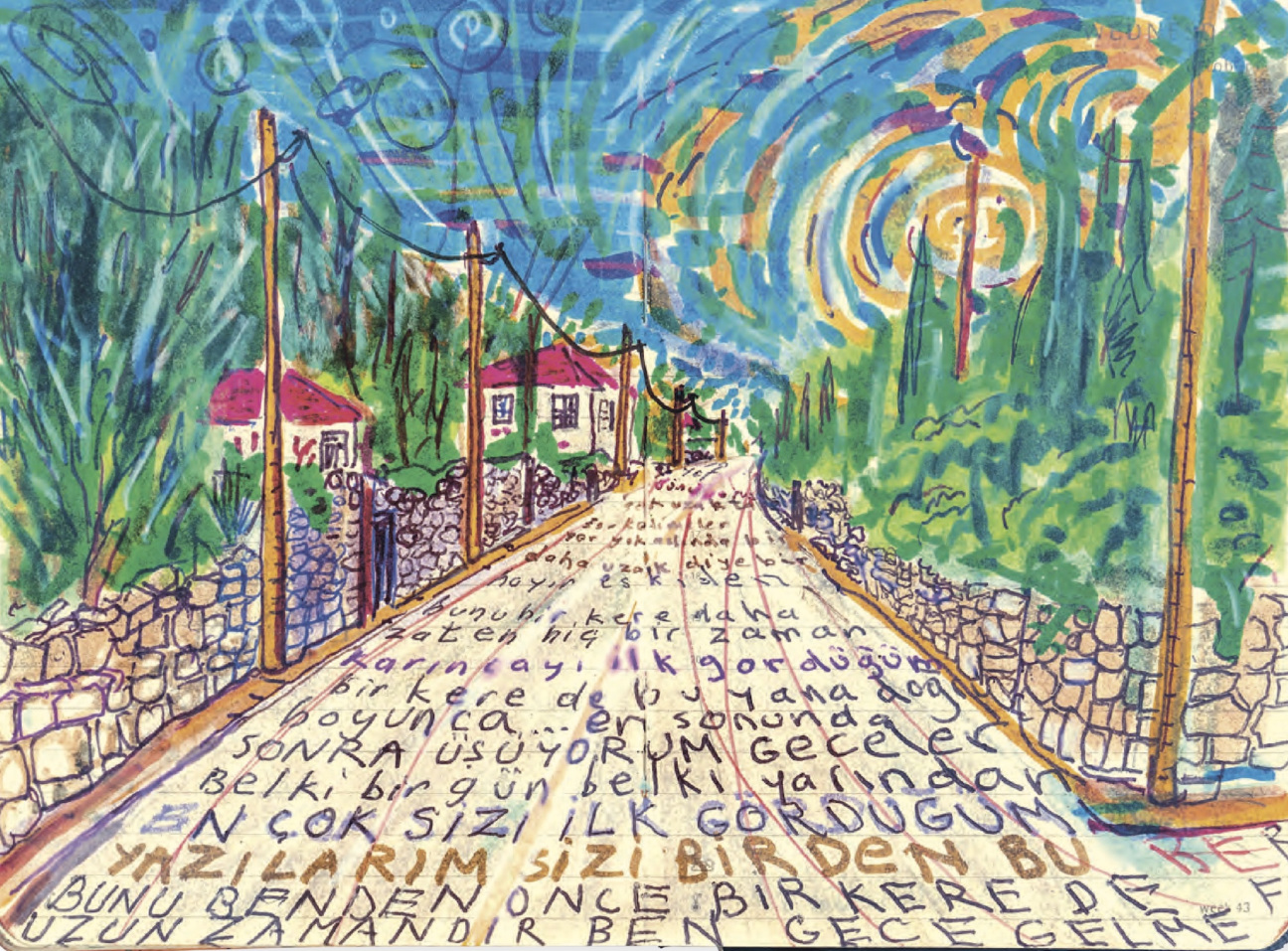

Banisadr: Having read many of your books, it was nice to get into your inner world and see how you grapple with ideas about your novels, about memory, landscape, dreams, words, and images. But one of the things that was really interesting to me, as a painter, is the part where you talk about how when you were making these drawings, sometimes the hand would start drawing on its own accord.

Pamuk: Now I’m an internationally known novelist, but, between the ages of 7 and 22, I wanted to be a painter, and I painted a lot. Later, when I switched from painting to writing novels for some mysterious reason, I saw a screw was loosening in my head. I wanted to kill the painter in me, because for 15 years I had wanted to be a painter. But the painter in me did not die in the end. One day, I went to a shop and bought a lot of painting material. Then I completed [my 2008 novel] Museum of Innocence, which is sort of an attempt to combine painting and literature.

I then decided to write a novel about the joys of painting, which turned out to be My Name is Red. I don't write my novels in one sitting. My first attempt was about a contemporary artist like you, where the events take place in Istanbul, but my artist was under so much Western influence. I didn’t want my novel to go towards problems of influence, East-West imitation. I didn't want to go into this subject, the very postcolonial, Orientalist, Westernization, modernity… I already wrote about them so much.

What I wanted to write about was the joy I had. I discovered the joys painters experience when they paint. I used to go to the Met and look at the miniatures no one looked at and try to imagine My Name is Red.

Banisadr: That's where I go, to see the miniatures from Tabriz.

Pamuk: Yeah, the ones the Ottomans looted when they invaded Tabriz.

So I wanted to write a painterly novel on the joys of painting. When I paint, I’m like a man singing in the shower. When I write, I’m like a man who is in a silent room playing chess or doing cerebral calculation and thinking. I feel more intellectual as a writer and less intellectual as a painter. Now I ask myself: Was being an intellectual more important for me when I was in my 20s?

Banisadr: You didn't kill the painter inside of you. Only painters look at things for so long and break them apart and put them back together and slowly observe. That's why I think the way you create your notebooks, where you have the landscape but then you also have the words, is true to the way you are. You're looking at it as a painter, but then you're painting it with words.

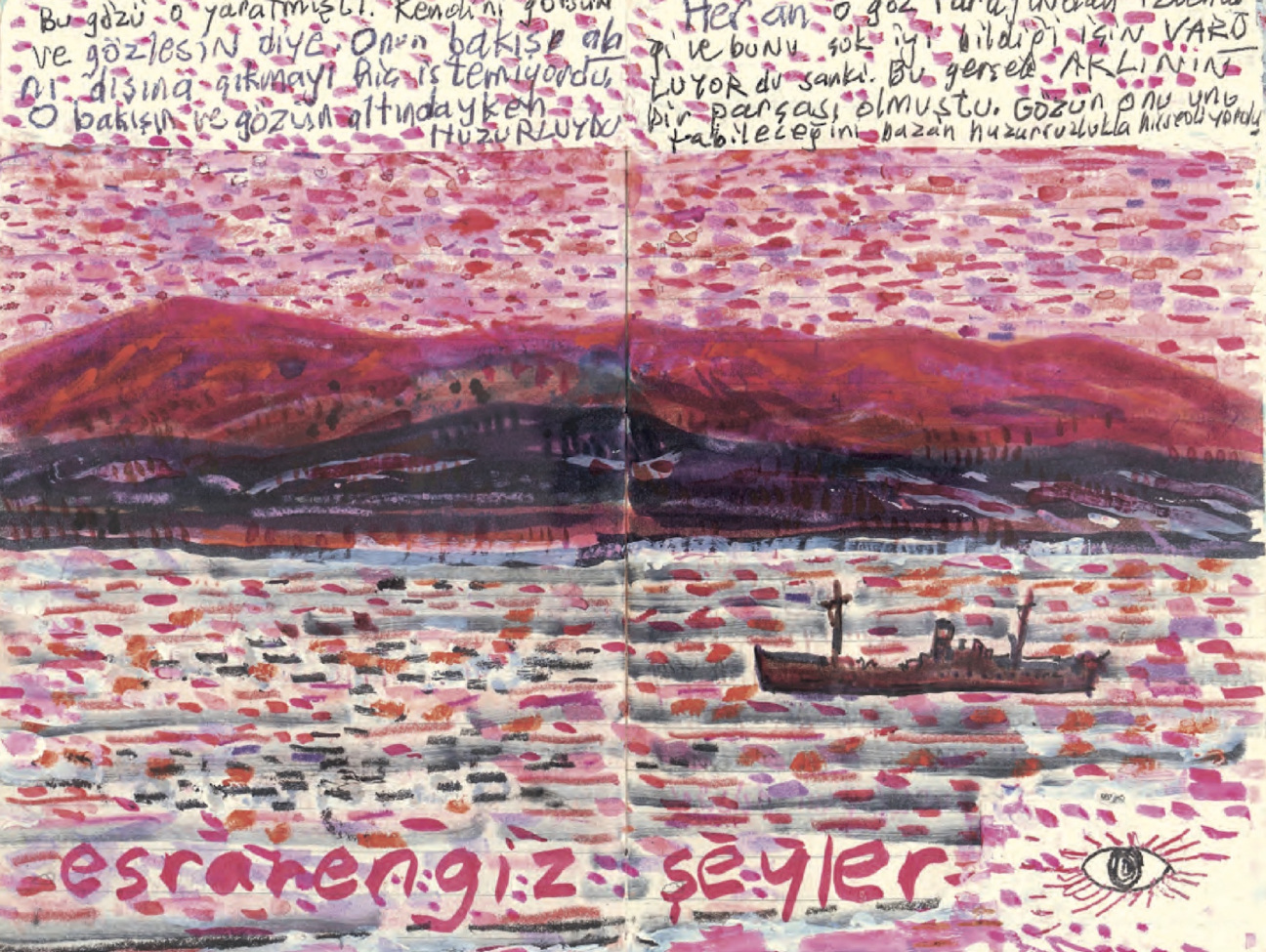

Pamuk: Yes, but on the other hand, what is this book? It’s a selection from my diaries. I've been keeping these Moleskine diaries, every day, for 15 years. I’m occasionally painting in them, doing double pages, doing watercolors in them. I have 35 small Moleskine journals like this, of which I filled 32. There are almost 6,000 double pages—of these, 800 are pictures.

They are not organized in chronological order, but in thematic or even sentimental order. You first see a page from 2014, you turn the page and then you see 2008, 2017, and so on. What? Why? Because they are all about landscape, or all about India, or all about not being able to write, or all about boats passing by in Istanbul or New York, or problems of a novel, or some fancy idea, or the writers and artists that influence me from Tolstoy to William Blake and Virginia Woolf to Calvino.

Banisadr: As I was reading your book, I was thinking of William Blake and, of course, there's a page where you talk about him. But in addition to Blake, you mention Cy Twombly, Raymond Pettibon…

Pamuk: Cy Twombly, Pettibon, Anselm Kiefer—these are painters who wrote over paintings. And I care about them.

Banisadr: Notebooks can be very personal things. I know myself because, just like you, I've had many notebooks where I write things down. But at some point I separated the writing versus the visual things. Next year, we're publishing a selection of my visual notebooks with Yale University Press.

Pamuk: Will there be any text in it?

Banisadr: A little bit.

Pamuk: Friend, make it more, not little.

Banisadr: Well, I have another notebook that's just for writing because I have a chaotic mind. I have to ground my thoughts, because if I don't, they just hover around and drive me crazy. So I have to ground them to understand them and deal with them. I know that you had to go through about 30 notebooks—was that a hard thing to do?

Pamuk: It was a hard thing to do—and I was helped by the Turkish editor Pelin Kivrak. First of all, what we care about are only the pages with pictures, which is less than a tenth. But even in that case, it was hard. Then there were pages produced to make the book more complete. For example, my editor told me, There are beautiful texts with the same themes, but in the middle of the double page, there's no picture. Why don't you do a picture of this theme so that there’ll be continuity? So there is also retouching.

I’m influenced by many other writers. In the 1930s, the idea of journal-keeping changed because the French writer André Gide published [his] when he was still alive. No one was doing that. Suddenly, this very private space turned out to be a living space, a creative space. Before that, diaries were a place where you wrote your secret visions, where you buried your money, or you hated your king or your father or whoever. More modern writers—[Austrian novelist] Peter Handke, many Turkish writers—began to, under the influence of Gide, keep diaries and publish them. These journal-keepers not only recorded daily things and ideas they thought were important, but also wrote creative, experimental journals as a space for invention.

The journals in Memories of Distant Mountains also have this quality. I may open a diary page I wrote 10 years ago and add a few lines here, a little landscape there, so the diaries are never finished. I'm adding both paintings and texts. Sometimes I do a painting of a boat on an empty page and never touch it again. Or sometimes I write a text and leave a space for a painting and never do the painting. Or, five years later, I do that painting. So that’s how the double pages for Memories of Distant Mountains were selected.

Banisadr: You talk a lot about dreams. There's this quote I really like that you talk about: “Dreams are not ekphrastic. Dreams cannot be described, only felt. The only way to transport the mood of a dream onto paper is to paint it in watercolor.” Do you write your dreams?

Pamuk: No. Once a year, once every 15 months, I have a strange, scary, moving dream, and right after it, I remember it for 10 minutes. If I write it [down] in those 10 minutes, I remember it. But if I don't write it, I forget it forever. It was the novelist Henry James who said, “Tell a dream in a novel and lose a reader.” [Laughs.]

Banisadr: But then you also talk about the dream and memory sometimes getting intertwined.

Pamuk: I agree that the power of dreams are [that] 99% are visual. There is nothing literal in dreams. It's an impossible job to convert a 99% visual world into words. But we attempt, we ekphrasis our dreams.

I argued in my book The Naive and Sentimental Novelist that novel-writing is first imagining the scene as a picture, then a crisis in that picture, so the reader reads that text and tries to form the same picture the writer has in his or her mind. So pictures are important.

What I see in my mind may also be confused with or intermingle with what I see in the world. In fact, this intermingling is art itself, the artistic activity. But in the end, I strongly argue that there were first images, things—before words. Perhaps because I wanted to be a painter.

Banisadr: Last question on your future projects. I've seen this title, The Story of a Painter, which I'm very curious about.

Pamuk: My imagination produces a lot of painter stories. I already wrote one, very cryptically, in My Name Is Red. I also have novellas, novel projects about painters. This subject—the contemporary painter who doesn't want to be influenced, but also wants to be authentic, deep, successful, happy—is my problem.

One of the reasons why I decided not to be a painter was, when I was 18 in Istanbul, there were only three galleries. One was government-run, one was [run by] a very dear woman who was even older than my father, and one was accidental, something small. You may want to paint, but then you need to find people who would look at [your paintings]. I can't say I'm regretful that I'm not a painter, but I can’t say that I'm not regretful I'm not a painter.

Banisadr: It's still in there—in your novels and in your new book here.

Orhan Pamuk’s Memories of Distant Mountains: Illustrated Notebooks, 2009-2022 is out now. Ali Banisadr’s current show “The Fortune Teller” is on view at Perrotin Shanghai until December 21. His solo exhibition, "Ali Banisadr: The Alchemist," will open from March 16 at the Katonah Museum of Art in New York.

in your life?

in your life?