Stacy Skolnik meets me beneath Montez Press Radio, the station she co-founded on Canal Street in New York’s Lower East Side. We decide to order wings at Forgtmenot just like the characters in her first novel, The Ginny Suite, out tomorrow.

“The original title was actually The Ginny Suite; or, The Victim Who Was Perfectly Fine,” Skolnik confesses. The now snipped subtitle was an ode to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, which Skolnik thought about often while formulating her own meta-narrative skeleton. “What I like about Shelley’s structure is that you can’t trust any of the information, because by the time it reaches the reader it’s been through too many hands,” the writer explains. “You can’t know what’s true of what you’re consuming. It reminds me of what it’s like navigating the world today. It’s hard to know what’s real and what’s artificial; what’s real and what’s been distorted through a relentless game of telephone.”

Another thing Skolnik likes about Frankenstein is the misnomer it proliferates. “So many people wrongly refer to the monster as Frankenstein, but Frankenstein is the doctor. The monster remains nameless, and yet he’s the image we conjure when we hear that name. Not the maker but the made,” she says. In The Ginny Suite, we never learn the protagonist’s name. We only learn the name of her foil: Ginny, a victim of a mysterious global syndrome robbing women of their will, who ultimately revolts against her partner not unlike the monster in Shelley’s text. Almost robotic in her passivity, Ginny does what the narrator will not. She violently assaults the patriarchy. Ginny’s action serves as a sharp contrast to our protagonist’s self-described “sleeping princess” apathy which applies to everything from her less-than-satisfying extramarital sex life to A.I. It’s easy in this dichotomy to fantasize about becoming Ginny– the perfect wife who one day turns on their malevolent spouse–yet it's impossible not to identify more deeply with our narrator in her small acts of self-sabotage—from holding her pee until she can’t anymore to going home with the wrong guy.

When binging The Ginny Suite this summer on a lounger, many readers might gloss over the affinities being stacked between Skolnik and our anti-hero. The novel is an autofiction that is very aware of what that container can do. Skolnik plays with the genre’s diaristic idioms and blends it in with the modes that came before it: the mass market romance, the sci-fi, the apocalypse thriller. In our era of sharing, autofiction has begun to feel just as archetypal, and Skolnik deftly sets up that comparison.

The author also sets herself up to toy with the genre’s bleeding edge, i.e. where it meets the real people in one’s life. Skolnik, like so many of us today, has stalkers and estranged family members. And now that I’ve known her more than a year—thanks to a Seth Stolbun introduction—I couldn't help noticing all the personal details and easter eggs she left behind in The Ginny Suite for these followers to perhaps glom onto and spin into valentine-sized conspiracies, or actions. I ask her about Netflix’s Baby Reindeer, which she hasn’t seen, and end up giving her a synopsis even though I’ve only watched two episodes. I conclude saying it's brave to find empathy, maybe even love for one’s stalkers, and to leave oneself exposed. She pauses. “Isn't that what everyone is doing to a degree? Plastering all this intimate information about our lives online for everyone to see? Everyone has stalkers now, and we’re all stalkers ourselves. That's the nature of living these public lives where we willingly disclose everything about ourselves…”

On that tip, Skolnik tells me that she recently gave a galley of her book to a guy she used to see. He said it disturbed him and wouldn’t read on. She says he isn’t the only one. During earlier drafts, multiple close male friends expressed genuine concern around the protagonist’s loneliness and what it might signify. We both laugh. This is the effect Skolnik hopes to have—the disquiet and the humor.

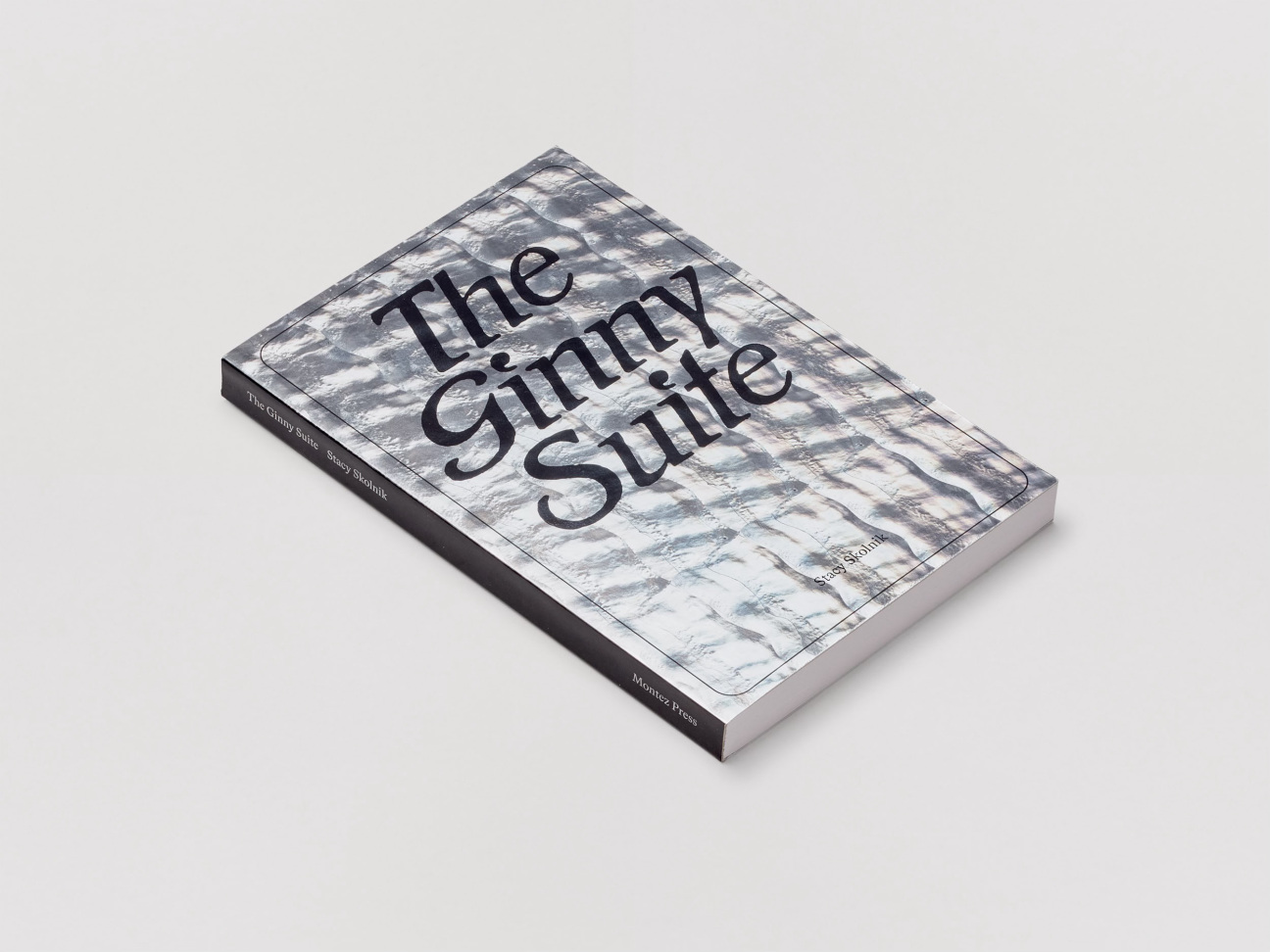

It makes sense that The Ginny Suite’s cover is reflective. The image it throws off is forever distorted by its beholder.

in your life?

in your life?