“It is all very ephemeral and quickly forgotten,” says Joyce Carol Oates when asked about social media. She offered this linguistic equivalent of a hand wave in response to a years-long fascination with her puzzling online presence. The author joined Twitter, now X, in 2012 on the suggestion of her publisher, Penguin Random House, and has since amassed an audience of over 250,000 followers who tune in to absorb, with both genuine interest and morbid curiosity, the unpredictable thoughts of a literary titan.

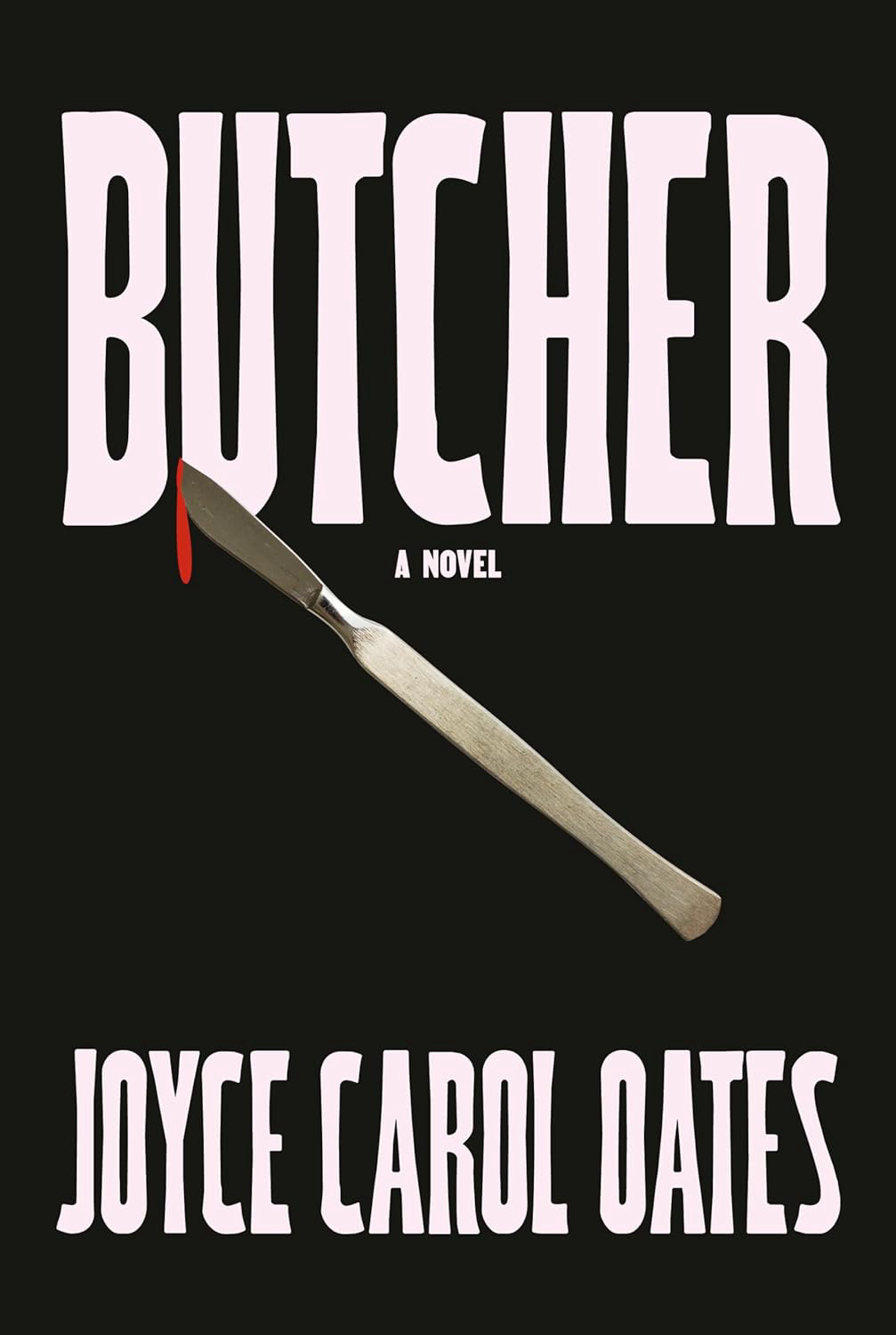

Oates’s musings are frequently political—bouncing from Trump, to the Israel-Hamas war, to Clarence Thomas—and only occasionally reflective of her career at large. The posts, which she fires off at the same velocity as her 50-plus publications—including the release of this month’s Butcher—have at various times achieved viral status for either their out-of-left-field sincerity (her cat pondering the Trolley Problem) or their blasé disregard for dominant socio-political leanings (“Is there nothing celebratory & joyous [about ISIS]?” she wrote in 2015).

When given an expanded character count, Oates’s writing prompts no such confusion. Butcher tells the story of a 19th-century physician who performs cruel experiments on female patients. The tale is loosely based on surgeon J. Marion Sims and presents a nuanced understanding of how gender intersects with race and class to create fluctuating power dynamics. “The story tells itself, with its necessary details. I am setting down medical history in a context of a fictional narrative with, to me, strongly delineated characters,” she explains. Tweets are scarcely capable of such subtlety, though they have become a primary currency of modern-day discourse.

Platforms like X, TikTok, and Instagram are where the next generation of readers reside. One can only assume this is why the writer, 85, was introduced to social media by her team (though she asserts no publisher has commented on her online activity since). Countless older creatives have turned to new media as a means of connecting with an extremely online public. The strategy can successfully hook a new, younger audience, but often results in a schism between how the creative was known, and who they present in this new format.

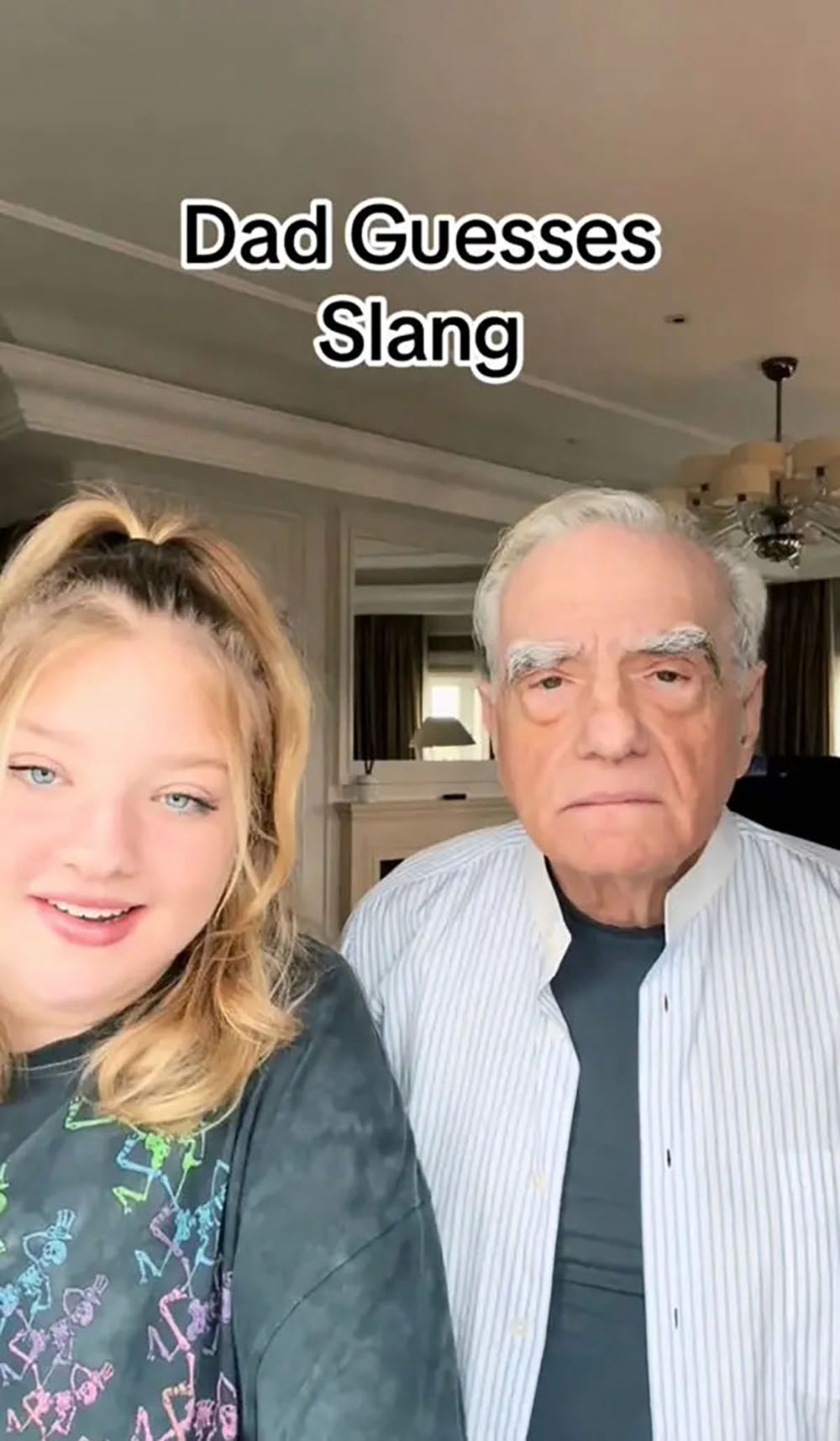

It’s a truism as old as Marshall McLuhan’s “the medium is the message” one-off. Established artists are forced to find themselves again outside the traditional channels and calendar of New Yorker profiles and photo calls if they hope to remain relevant. Consider Martin Scorsese, the monument behind such modern classics as Taxi Driver, Goodfellas, and The Wolf of Wall Street. Last year, he began racking up millions of views on TikTok with help from his Gen Z daughter, Francesca Scorsese.

Francesca told CULTURED that she considered “exposing [her] generation to older filmmakers, such as [her] father,” to be her biggest cultural contribution thus far. The daunting, and sometimes dusty, world of prestige film was given a new sentiment by the duo’s lighthearted skits. A few months into their endeavor, nearly half of opening day moviegoers for the director’s three-hour-long epic Killers of the Flower Moon were under 35. In a highly publicized move, Letterboxd then wrangled Scorcese into joining the platform last year. He quickly became the most followed user on an app where more than half of users are also under age 35.

Kyle MacLachlan has been able to inspire a similar fervor through his posts across social platforms. His dance videos and photo series echo the surreality of his early Twin Peaks work, dialing the actor’s particular brand of oddity up to 10 (social media’s resting rate). Though it can hardly be attributed solely to his meme-making proficiencies, MacLachlan’s most recent work, Amazon Prime’s Fallout, just became the most-watched production in the history of the platform.

The digital realm holds no such intrigue for Oates, who replies bluntly, “I don’t think of this at all,” when questioned about a desire to reach new audiences online. Fair enough: the National Book Award winner and five-time Pulitzer finalist is in no short supply of readers. She is an infrequent poster on Substack at invitation of the platform, where she reposts old articles and new, long-winded musings. So Oates, or someone in her circle, does on a base level understand the importance of digitizing her practice, as Substack and Letterboxd have likewise come to acknowledge the value of having legacy creators add distinction to their platforms.

What’s more interesting is Oates’s disregard for the potential consequences of posting. She must not be following J.K. Rowling, probably the most potent example of downfall via tweet. The millennial icon turned Gen-Z laughing stock regularly voices such obvious disdain for transgender women that supporting her career has become a wholly political act. While she writes, “being female is indeed defined by our biology,” Gen Z has made history as the first generation in which over half of adults believe there are more than two genders.

Oates’s railings against the establishment are more in line with youth fervor, though several flippant comments feature prominently in the new, dedicated “Twitter” section of her already sprawling Wikipedia page. There was a ham-fisted connection drawn between Islam and high rates of sexual assault in Egypt, that odd query about the lack of levity in ISIS’s organization, and a cheap shot at Chinese diets (i.e. literal “cat food”). In 2022, she wrote, “(a friend who is a literary agent told me that he cannot even get editors to read first novels by young white male writers, no matter how good; they are just not interested. this is heartbreaking for writers who may, in fact, be brilliant, & critical of their own ‘privilege.’)”

She contextualized her statement to Bustle later that year, adding, “Of course, I don’t think that white people have been disadvantaged … White male writers have been the mainstream for millennia, but I would just assume that everybody knew that.” Therein lies Oates’s critical error: assuming that the Twitterverse leans sympathetic, or could ever be painted with shades of gray. In recent years, coverage of her work has inevitably featured a detour discussing her tweets. When pressed on the subject, her response always seems to circle around the same sentiment: Who knew people would care so much?

It’s a sharp distinction that separates older generations from those raised on “the Internet never forgets” warnings and online social circles. No one gathers around the radio anymore. Movie trailers aren’t premiered ahead of film screenings, but by @DiscussingFilm on X. We don’t get to know celebrities live on late night, but in YouTube clips posted the next morning or from parsing through their ephemeral Instagram stories. The golden years of long-standing careers will be defined by who is ready to embrace the changing game, and who isn’t. Oates, for her part, seems to know more than she’s letting on. She’s already retweeting early coverage of Butcher.

in your life?

in your life?