Kate Zambreno has been re-reading Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick. More specifically, the late queer theorist’s seminal text, “Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading, or, You’re So Paranoid, You Probably Think This Essay Is About You.” In her 2002 essay, Sedgwick prods at the supremacy of the paranoid mode in critical analysis, which she associates with being definitive and defensive, and suggests an alternative tradition of reparative thought, which dwells in the realm of the potential. “Sofia is always saying to me that the Internet, or criticism by its nature, is paranoid,” Zambreno tells me, speaking of their longtime thought partner, Sofia Samatar. “It wants to find the faults, but so much of my work is reparative. It comes from a depressive position, which is one of love.”

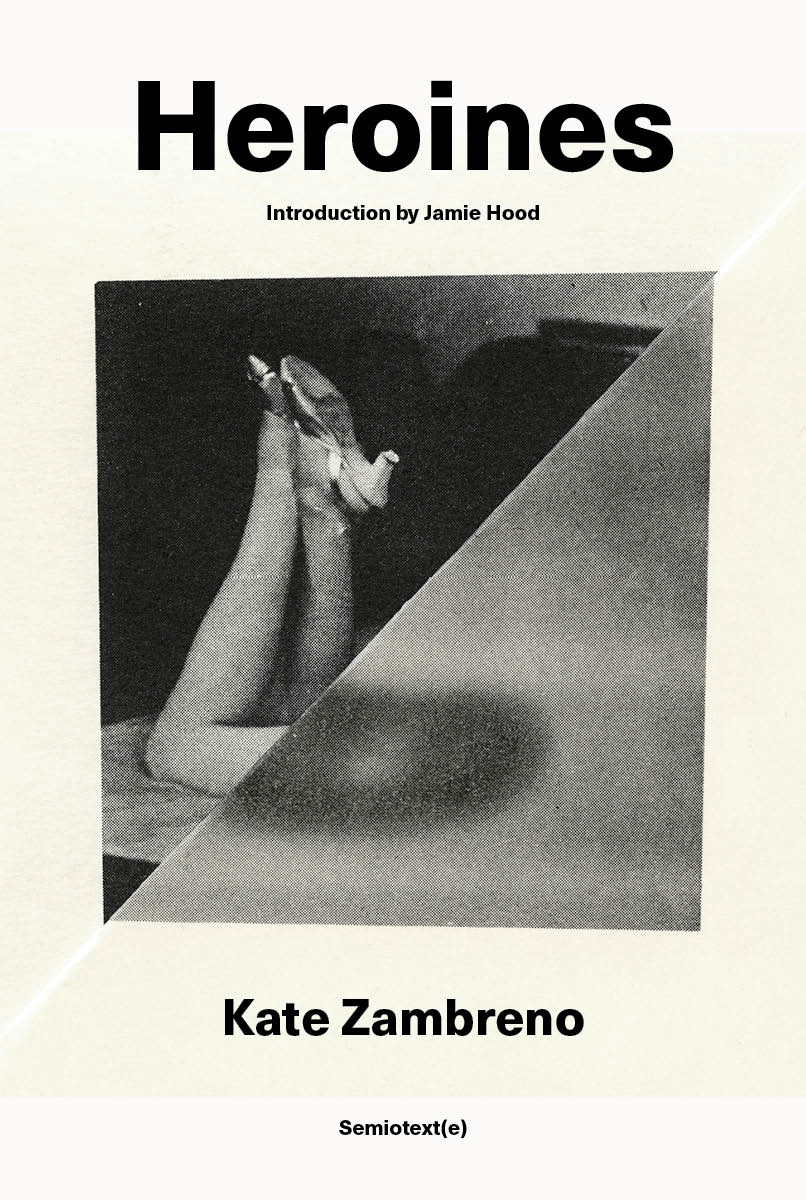

Heroines hit bookstore shelves 10 years after Sedgwick published “Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading.” Zambreno’s third book, it announced the Midwestern native’s entrée onto the literary scene—and into the jaws of the critics’ circle. The tome’s tumultuous initial reception is well-chronicled; its reissue with Semiotext(e) earlier this month may have landed at a time where the literary world is more primed for its irreverence. A roving “group biography,” it pairs the author’s reckonings with boxes like “writer,” “wife,” and “mad” with an excavation of the maligned lives of the “madwives of modernism”: Zelda Fitzgerald, Jane Bowles, Vivien(ne) Eliot, and Sylvia Plath, but also June Miller and Djuna Barnes.

Over its 300 pages, Zambreno resists tidiness and convenient conclusions, slaloming from the indulgent and the inconvenient to the furious and combustible. Heroines is a retroactive lifeline for its muses, an attempt to repair or restore their places in the literary canon. To mark its reissue and its author’s own ascendance into a canon of elective affinities, CULTURED sat down with Zambreno to talk about horny literature, moving beyond the first-person, and why we need the anti-lyric more than ever.

CULTURED: Heroines was published 12 years ago. Re-reading the book for this reissue with Semiotext(e), what was it like to re-encounter the Kate Zambreno of that era?

Kate Zambreno: I went through a period of feeling cringy about the work because there was a real critical backlash. And I think that was because I was such an outsider to New York media. At the time, I felt shame about my outsider status. I probably started a lot of the material for Heroines 20 years ago. But from the point of view of being 46, I really admire how outsider the book is, how it’s attempting this incredibly energetic, bodily criticism. I feel so much more amazement at this person who didn’t really know any rules.

If you had asked me a couple years ago, I would have said my work is completely different from Heroines. But in work post-The Light Room, 2023, I actually think I’m going back in some ways to an almost Nietzschean spirit of resentment. Heroines is so horny. I was talking to someone the other day, and I was like, “Horniness is such an amazing quality of literature. It doesn’t get enough credit.” That’s all I want to read—something that’s absurd, something that’s horny, something that has fury and also deep sadness. It’s not just about re-reading Heroines, but also contending with the persona people made of me [after its release]. People put me in a certain box when they wrote about Heroines, but I think the work itself is a lot trickier and more slippery. It’s a young work, but I could never write with that sort of feralness again.

CULTURED: There’s a shamelessness to the book; it bangs at the doors of anyone who will listen. There was backlash to Heroines, but it was also life-changing for a lot of readers. In the introduction to the reissue, Jamie Hood writes about the book “saving” her.

Zambreno: That surprised me. I’ve been friends with Jamie for a while, and I had no idea. I get uncomfortable with a statement like that. Like Kristen Stewart talking about [me] in Rolling Stone. There’s a very self-effacing part of me; it’s very Midwestern. Like, Oh, you should read other books. I was writing outside of academia, and I was writing for Chris Kraus with that inheritance.

CULTURED: How did you meet Chris Kraus?

Zambreno: When I applied to the Columbia MFA program—which I did not go to—I asked Lauren Berlant for a letter of recommendation. I tore it open and read it. And it was not a positive recommendation. It said, “Kate has given you her serious self. Soulful in that ‘90s feminist kind of way. But I know, because of reading her alt-weekly pieces, that there’s this mischievous spirit inside of her. She could become the next Chris Kraus or Kathy Acker.” I adored Kathy Acker, but I remember being like, Who the fuck is Chris Kraus?

O Fallen Angel [Zambreno’s debut novella] was published with a tiny press started by Lidia Yuknavitch in 2010. I asked Chris Kraus to blurb. Then I started this blog when I was in Akron, Ohio, and she and Hedi el Kholti [who runs Semiotext(e) with Kraus] started reading it. They were like, “How would you like to write a book for us?” They saw something in me. Then, after I wrote Heroines, I read Chris Kraus’s work and loved it, but felt so glad I didn’t read it before because I would have been so paralyzed at the kindredness of our interests. What was cool about Heroines was I began to realize that so many other writers were obsessed with the people I was passionate about—all these elective affinities. That’s maybe what younger readers [feel] when reading me. It’s not just the writing; it’s the permission to write about archival obsessions.

CULTURED: It’s in the The Light Room I believe where you talk about writing as an eternal return. There’s something about these books re-emerging every few years with new relevance.

Zambreno: That’s what literature is to me. I tend to read books over time, and I keep returning to them. I don’t read everything that’s new, but I will keep returning to works. Then you find something different about them, or they mean something different to you. That’s a really beautiful intimacy.

CULTURED: At the top of Heroines, you write, “I’m trying to learn how to be a serious writer and write important books, yet I cannot deal with all the silence.” I’m interested in you saying you can’t deal with silence because years later in The Light Room I feel like that’s all you’re grasping for: silence and time. You obviously became a parent and a professor in the years between those books, but how do you see your approach to writing shifting over time?

Zambreno: When I read Drifts, 2020, or Heroines, I view it like science fiction. I don’t think I’ll ever have solitude like that again. I was working a ton during Heroines. I was such a gigging adjunct, but I don’t really write about work that much in the book. I’ve developed more of an ethos of writing about work and being an adjunct over later works—mostly because I found myself in the absurdity of being pregnant and working way more than full time and having zero maternity leave. A lot of those works grew out of that sense of not existing or being seen as a valuable person in the places where I worked. There was even more of a political desire to write through that erasure.

Now, I regard writing as a space of freedom to me, even though it’s also work. But that sense of infinite time… I mean, I was paid a thousand dollars for Heroines, and it took me like four years to write it. It was such a big deal to be given a thousand dollars for a book … I will never have the ideal conditions to be a writer. It’s not just having children; I think it has something to do with the cognitive load of being a perennial adjunct, or with the work of being a writer, which has often involved a lot of service—like emailing and communicating constantly … But as I become more interested in precarity, community, and plurality, I’ve become less interested in myself. The writing is less important.

CULTURED: Although The Light Room is an act of writing as much as Heroines, it feels so much more interested in the life around writing than in writing itself.

Zambreno: I wrote two books about being pregnant—To Write as If Already Dead, 2021, and Drifts—and they’re both obsessed with male geniuses. Like, Can I be a pregnant writer and be [W.G.] Sebald? The answer is no. And I think that “no” is actually a lot of grace… The Light Room being considered a “mom memoir,” or me being asked to do wellness Instagrams, which I said no to, were huge fights [with my publisher]. Or me saying, “No, I actually identify as non-binary.” That experience made me realize that the outsider feeling of [Heroines] is something I still cultivate.

CULTURED: Heroines is so interested in the pathologization of excess. Pathology and pathetic obviously have the same root, pathos, and I did think a lot about Eileen Myles’s Pathetic Literature when reading it. In the intro to that, they write, “Each of these writers has a discomfort or a restlessness that exceeds their category somehow. Work that acknowledges a boundary then passes it.” I feel like what you do often in your writing is acknowledge the boundary of yourself and your experience and pass it.

Zambreno: I got so jealous they didn’t ask me to be part of that. Why aren’t I pathetic enough? But I think you just categorized what my impulse still is with writing. I’m just a small part of this much larger tradition of writing that is pathetic. It is interested in the abject and in the blurriness of the borders of the self. I’m teaching a seminar on Annie Ernaux at Columbia. It’s making me really meditate on expectations in nonfiction now as brought forth by the MFA. There’s such an idea in memoir of the stable self, or the therapeutized self. A self that’s been through therapy openly on the page and has epiphanies and wants the readers to have epiphanies.

This whole tradition of excessive literature explodes coherence, and the idea of the reliable narrator. Who is the self? Am I a self? A lot of that work can be like living affect theory, which is so different than living therapy in which one has an epiphany on the page and a sense of beauty, too. A lot of reviews of Heroines talked about how ugly the text was. I remember being so irritated by this The New Inquiry essay saying Dodie Bellamy, Eileen Myles, and I were “uncooked writers.” The cooked writers were Maggie Nelson and Allison Bechdel. No one edits themselves more than Eileen Myles or Dodie Bellamy. That casualness is incredibly difficult … There’s an artfulness about it, but it’s not always about lyricism or beauty. There’s space for an anti-lyric.

CULTURED: In Heroines, you write about the status of being a “wife,” grappling with that container and its discontents. In later books, you reckon with the status of becoming a parent or an adjunct. What are you becoming these days?

Zambreno: I am working on a cycle of three books that are all thinking around precarity, housing, and problems with the first person. I’m in this very porous period of my life. I am becoming more at peace with feeling queer or non-binary. I feel like I’m entering a new adolescence. Being middle-aged, still having milk in my breasts, maybe entering menopause but then feeling non-binary—I’m in this very ecstatic, strange period I’m trying to write through. What does it mean to be a nobody and a somebody?

Tone, 2023, and The Light Room gave me permission to enter this new body of work. Sofia Samatar [with whom Zambreno co-wrote Tone] and I are talking a lot about atmosphere with our own works. I really want this next body of work to be meditating on the atmosphere of capitalism, and I’m trying to figure out how to do that within a text. I’ve written about being an adjunct in past works. The Light Room deals with it, but it’s so interior. I’m still coming through with what it meant not to have maternity leave. People who don’t get what it means to not have sick leave or maternity leave, they don’t get it. Because what that means is actually quite brutal.

CULTURED: Sofia has been a crucial conversation partner over the years, so has your partner John. But many of the people you’re addressing or conversing with in your books—Joseph Cornell, Hervé Guibert, Zelda Fitzgerald—are dead. They can’t respond. What does that afford you, and does it ever feel like a trap?

Zambreno: With Heroines, there’s an argument people made that I took these lives and co-opted them. Right now, I’m trying to write this document that’s kind of a novel that deals with my collaborations with B. Ingrid Olson, who’s very alive, but also thinks about Eva Hesse. So I am really thinking about when I bring in the lives of others [into the texts] … Someone who read The Light Room said they thought of the work as art criticism, and I don’t really identify with that. I often am just really thinking through someone. I do think I have less emphasis now on their biography. What I am really looking for are those who made art amidst homophobia, mortality, capitalism… Like, How do we do it? How do we have any time to make art? What if art doesn’t survive us? Maybe it is about a daily impulse of it. Maybe it is about the joy.

CULTURED: You mentioned this at the beginning of our conversation, but many terms and labels have been projected onto you over the years. People have described your work as self-centered. Someone called it “reparative vampirism.” How do you want to be seen as a writer?

Zambreno: What’s really funny to me is that I’ve stopped caring. I don’t like being published by a corporate publisher where I’m supposed to be like a “mom writer,” but beyond that, I also don’t want to be a sage. I think criticism is good. I’m glad it’s alive. I’m even glad when it’s snarky. I think it’s okay to have a negative or even hostile or resentful reaction to something. Resentment is a really palpable force. But a lot of criticism comes from thinking that I have power when I don’t in my day to day. I note my huge privilege being published, and that there are so many voices that should be more magnified than my own, but I’m not a very powerful person.

The problem with the writing world is how connected it is to capitalism. There was not a single review [of Heroines] that wasn’t by a very mainstream media person, who went to an Ivy League, is wildly more successful than me, and was just like, “Why is this person allowed to take up space?” When Heroines came out, Anne Boyer said something to me. She was like, “It’s really a strange experience when one of our books is read by someone outside of our community.” Maybe people need me to argue against, or to think about their own work. You’re not supposed to agree with everything in a work. It’s not supposed to echo everything you think about the world.

in your life?

in your life?