For years, the New York-based indie publisher 8-Ball held zine fairs at pool halls around the city. They were low-key, relaxed affairs. “The question of needing to manage the crowd or how many people to expect never came up—it just wasn’t a thing,” says Ryan Vasta, 8-Ball’s co-director.

Everything changed after the pandemic. For Valentine’s Day 2023, 8-Ball held a zine fair at the Sixth Street Community Center in the East Village. The organizers invited no more than 20 exhibitors, but the place became as packed as a hot bar on a Saturday night. For the first time, they had to think about things like fire codes and line control. “It was just way too crowded,” Vasta says.

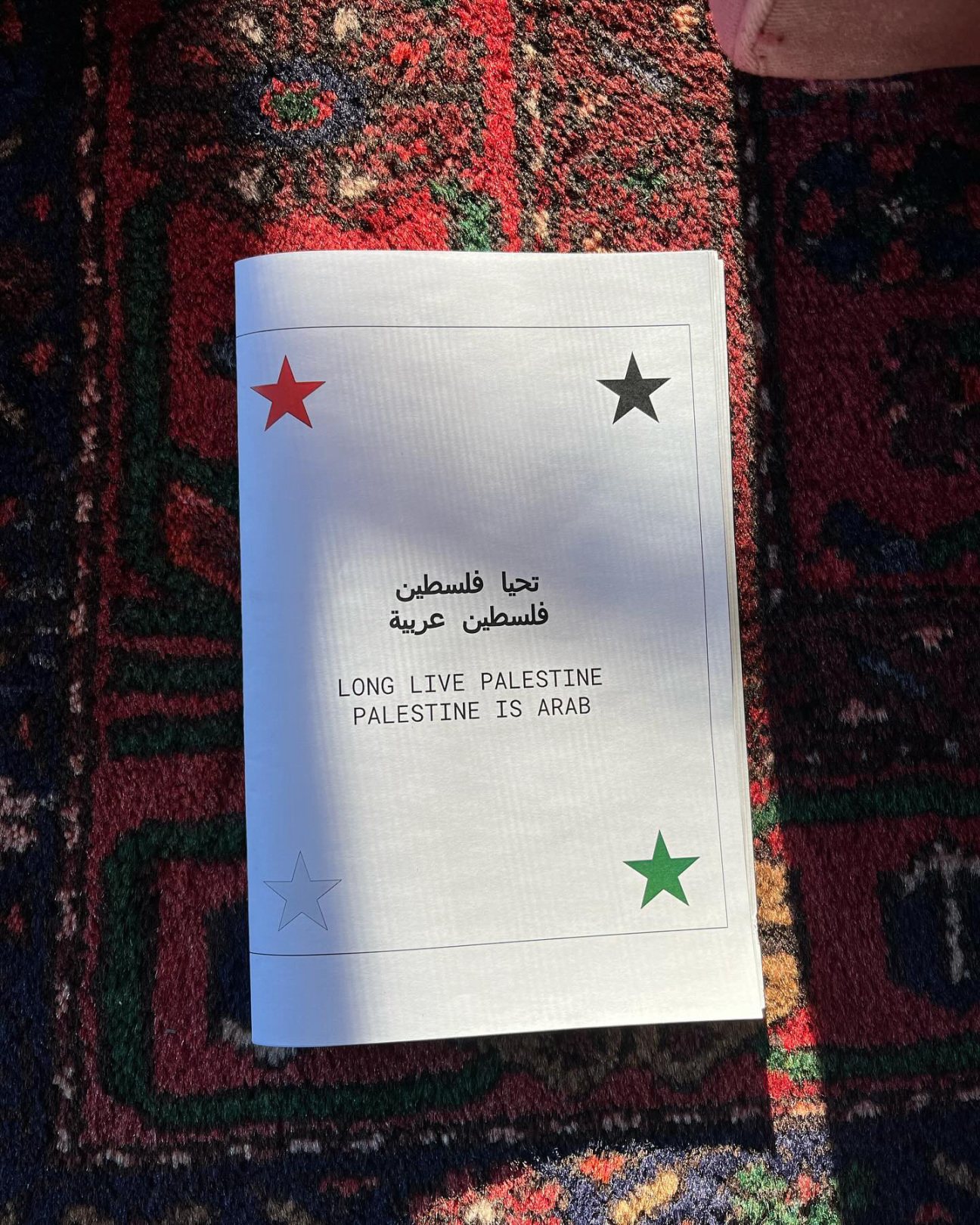

Interest in zines—small, self-published printed texts and images—has ballooned in recent years. The spike can be attributed to young people’s growing disengagement with social media as a tool for political communication coupled with a renewed interest in community-based advocacy and tactile, IRL cultural objects.

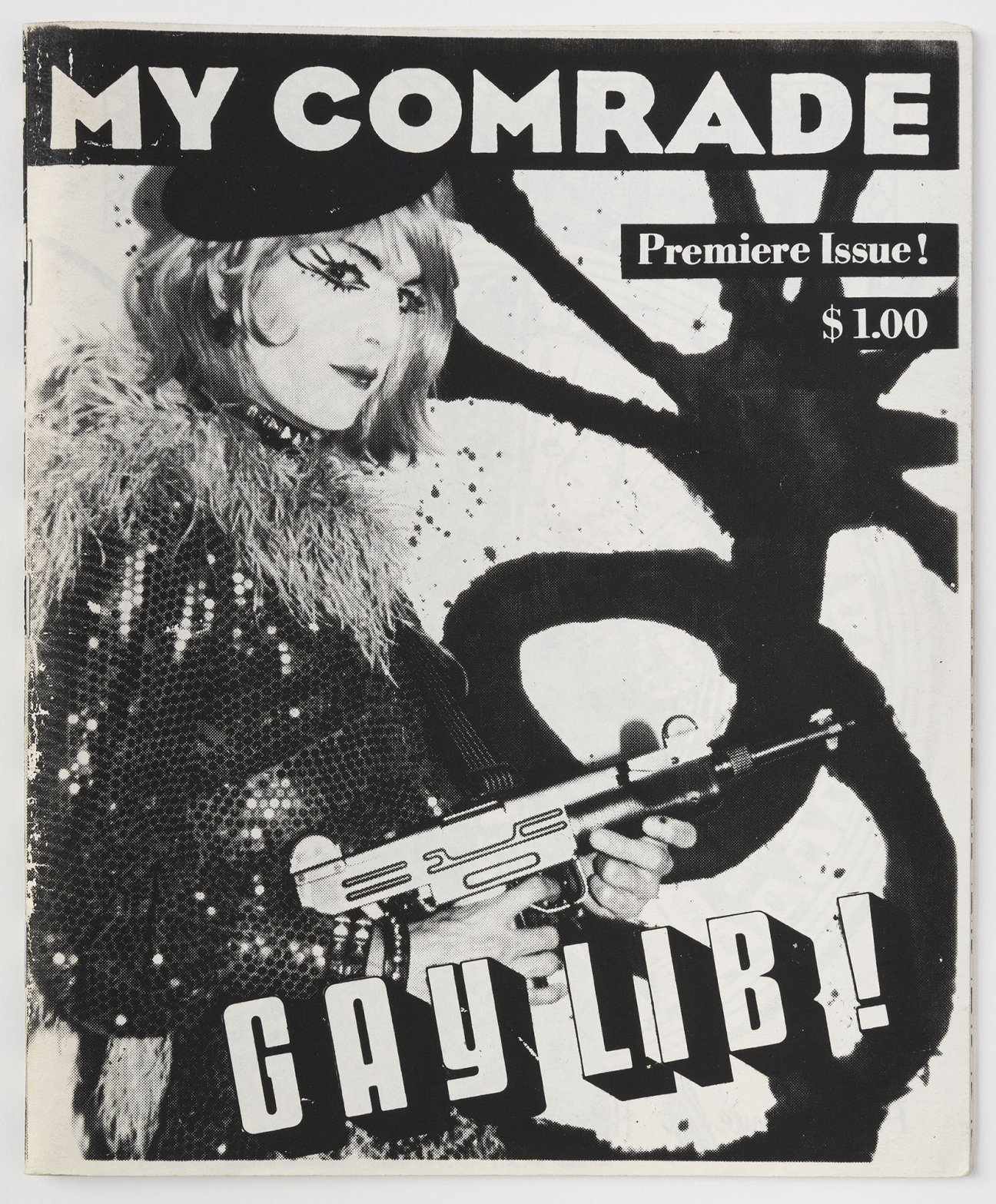

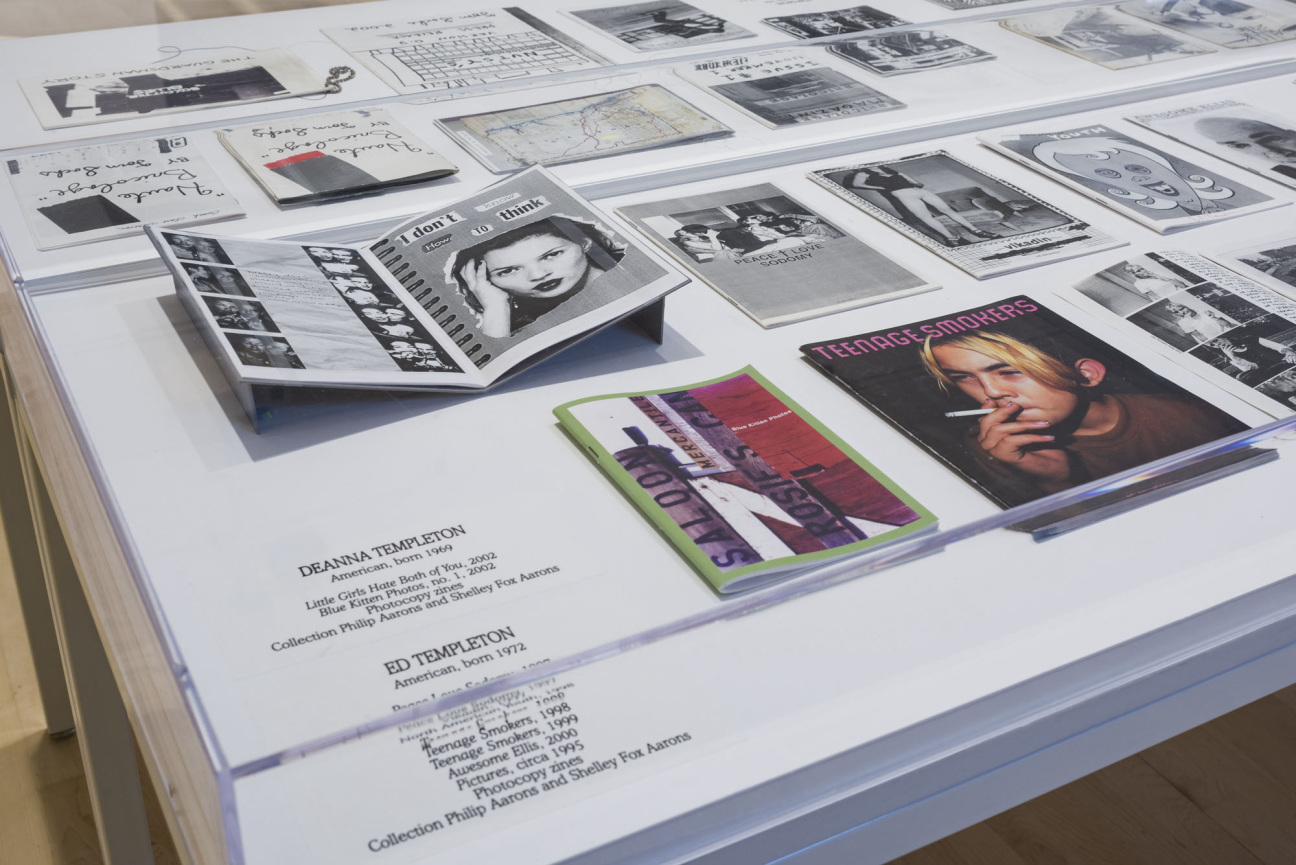

Zines, short for “fanzines,” have a long history of artistic and political engagement, according to Branden W. Joseph, who co-curated “Copy Machine Manifestos,” an exhibition dedicated to the subject at the Brooklyn Museum (on view through March 31). Although many associate zines’ origins with punk’s heyday, the photocopied or hand-stitched papers were in fact an invention of Trekkies, one of the original fandoms. Progenitors of the form include Black writers in the 1920s who wanted an avenue for publishing outside of the mainstream and, even further back in time, 18th-century thinkers and authors of political pamphlets Thomas Paine and Benjamin Franklin.

The Brooklyn Museum show is the first institutional exhibition dedicated to the medium. “Most people think that punk created the zine and then artists latched on to it,” says Joseph. “But we can show that, in some ways, punk latched on to what the artists were doing.” More than 800 works in the show explore zines as an essential art-making tool in queer, feminist, punk, and other subcultures.

For Lizania Cruz, an artist in the exhibition, zines tap into a long-running cultural conversation around care in communities. Her “We the News” project, 2016-2022, is a traveling newsstand stocked with zines detailing the stories of Black immigrants and first-generation Americans. “Because of the nature of the medium that is so easy to reproduce and distribute, it’s always in reaction to a political [moment], subculture, or a community,” she says.

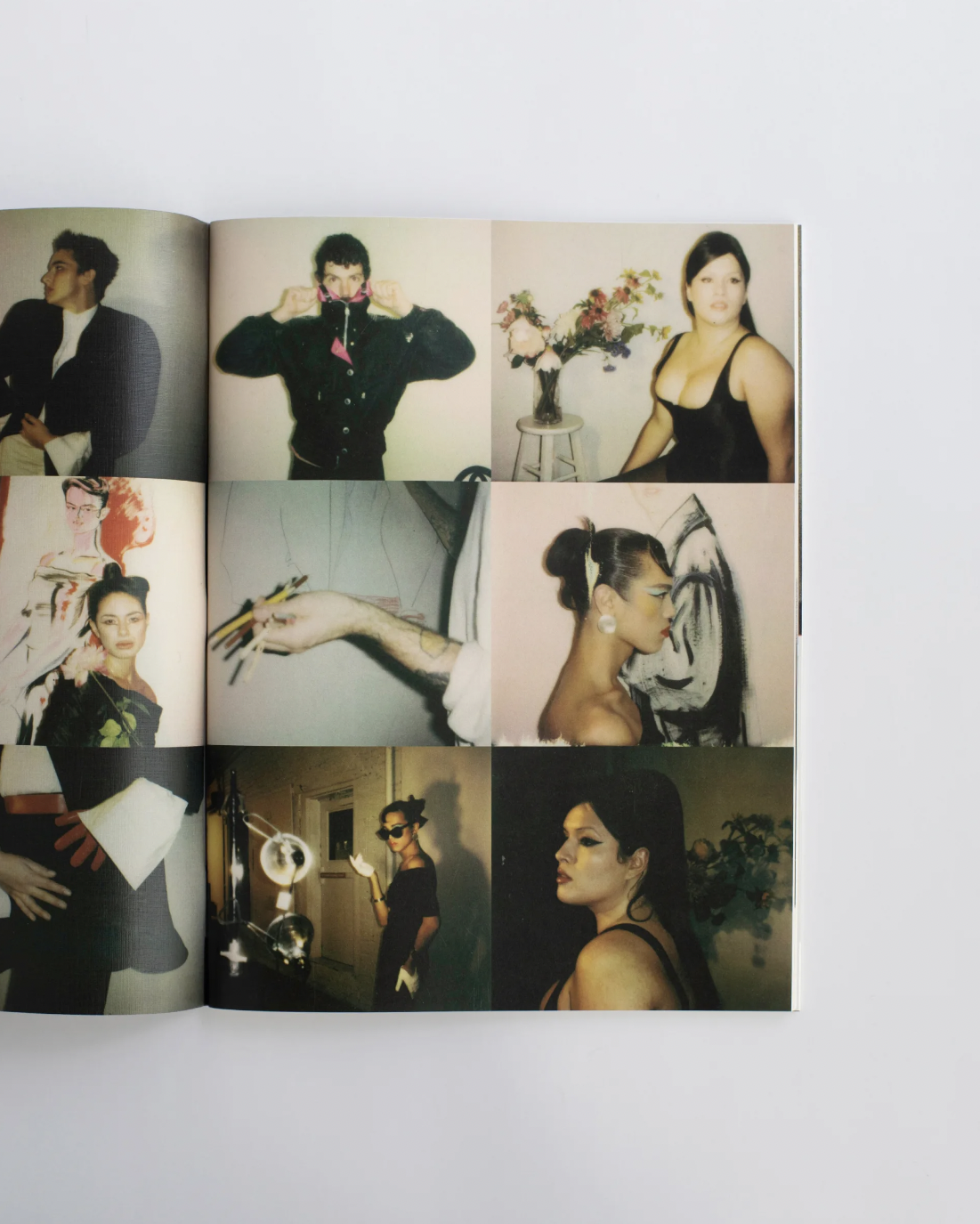

The dividing line between zines and traditional magazines or artist books is the immediacy of production. Zines require no formal publishing contract. “A zine can be a single thought or idea, perhaps pictures that a photographer takes quickly,” says Ethan James Green, founder of New York Life Gallery, which has been formalizing the zine-making process with a number of glossy releases by artists like Daniel Arnold, Steven Cuffie, and Sam Penn.

For Drake Carr—whose exhibition at New York Life Gallery last January included live drawing sessions and resulted in a zine stocked with event photography and sketches—the form is a way to capture the spirit of a moment. While the majority of our records exist online, Green’s publications provide the opportunity for “people to take something away with them from the exhibition.”

Tangibility has proven to be a selling point for younger, digitally native audiences. Music fans have been going back to records for several years now—in 2022, vinyl sales were up for the 16th year in a row, and accounted for 43 percent of album purchases. Physical book sales have remained steady, even seeing a slight upward trend since 2021.

Meanwhile, users are becoming less loyal to behemoth social media channels like Twitter (now X), Facebook, and Instagram. In 2021, Pew Research found that 70 percent of users rarely or never posted their political views online, the top reasons being that they don’t want their posts used against them or to be attacked for their views. At the same time, America’s trust in mass media is hitting record lows.

“In the late 1960s, early 1970s, artists were attracted to [zines] because it allowed them to both control the production of their own material and the distribution,” says Drew Sawyer, who co-curated the Brooklyn Museum show with Joseph. “That’s as true today as it was then, especially when so many platforms that allow us to share information are corporate-owned and are therefore prone to surveillance and censorship.”

Zines’ future relationship to the Internet remains up for debate. By the broadest definition, a zine can be any self-published item. At the Brooklyn Museum, zines recorded on camcorders in the ‘80s are on view, as well as other digitized examples from the advent of home computers in the ‘90s. These days, academics are asking whether a curated Instagram or virtual collage can function as a zine.

For the time being, however, a big part of the form’s appeal remains rooted in nostalgia for times when community action was organized locally—built upon information that was passed, quite literally, from hand to hand. “Zines are made to be distributed, but they’re made to be distributed the way that you want to distribute them, the networks you want to distribute them in,” Joseph says. “There’s something that’s secret and intimate about zines that allows people to express things in a way that is public—but it’s maybe a restricted public, a secret public, a counterpublic.”

in your life?

in your life?