On a Saturday Night in October, I took the B41 bus to Flatbush to hear Fran Lebowitz. As I milled around the Kings Theatre’s gilded lobby with the Fran-fans (hot 20-somethings, married lesbians, members of food co-ops), everybody—even the diehards—seemed curious as to what exactly the performance would entail.

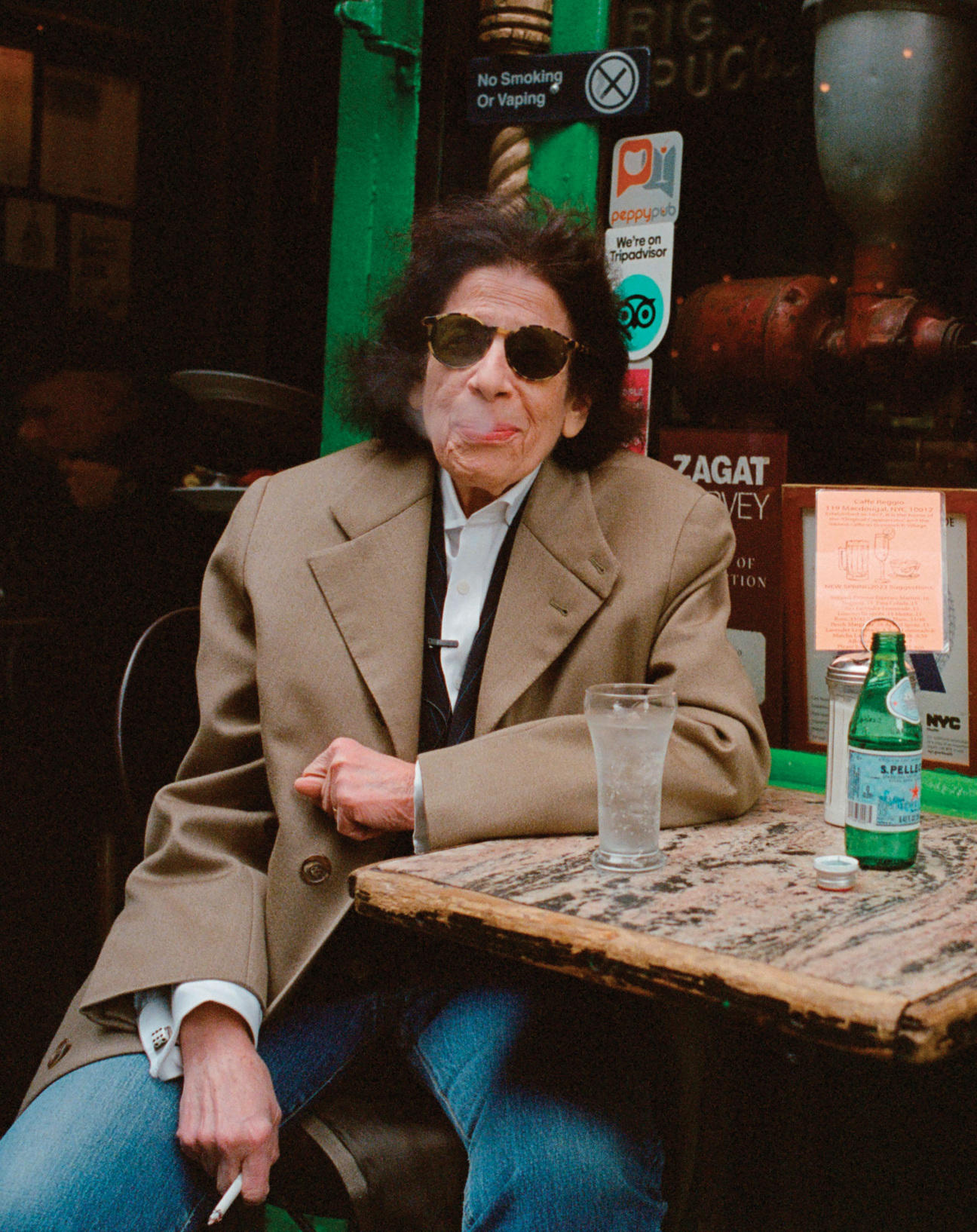

It was a talk. Fran Lebowitz is a talker. She’s also a wit, a woman of (few) letters (her slender volumes Metropolitan Life and Social Studies were combined in 1994 into the still-slender Fran Lebowitz Reader), an inactive activist (Fran is an outspoken lesbian and political presence), a smoker (she’s smoked so long it’s cool again), an actor best known for playing herself, a Martin Scorsese muse (see: Pretend It’s a City and Public Speaking), an orator, a New Yorker, and a curmudgeon. She’s a cowboy boot-wearing, buttoned-up, fast-talking icon. To Fran, everything was better years ago, and even then, things weren’t so good.

What, I wondered as I watched the theater fill, is Fran Lebowitz’s legacy? While she may seem an unlikely hero for young New Yorkers, she’s polling Bernie numbers, and I think the answer runs deeper than a Netflix show introducing her to new audiences. In her approach to the world, I see all my fears refracted: The threat of ever having to “do” something with your life, the terror of writing a book, or (and this one is personal to me) a second book, or, God forbid, a third.

Beyond the existential anxieties that have spooked humans since they first dipped nib in ink, there are also some new fears, like the sickening idea of relevance. Maintaining a place in current society means continuing to produce, well, anything. Often, I feel like I’m on a hamster wheel, working, posting, going nowhere, eating kibble. We’ve created a culture that’s too fast and too greedy for our own comfort.

Detaching from my phone is impossible; any act of creation is welded to self-promotion. Our experiences are mediated by an imaginary board of fans. How can we please them? How do we create to satiate our own magnified expectations? We’re so caught up in ourselves that it can be hard to recognize time passing.

Often, Fran told her Flatbush disciples, young people ask her for advice on how to live. Like she knows the right way to live, or like there is a right way to live. Maybe it’s because Fran has no cell phone, computer, or typewriter. This means that, for all her nostalgia and reluctance to change, she possesses contemporary culture’s most coveted prize—she is incredibly present.

In this sense, Fran, who claims she’s “always been old at heart,” is really very young. In “My Day: An Introduction of Sorts,” from Metropolitan Life, Fran gives an introduction to her day, which involves oscillating between a semi-recumbent position on her couch and a fully recumbent one in her bed.

She writes of the mail she receives: “Nine press releases, four screening notices, two bills, an invitation to a party in honor of a celebrated heroin addict, a final disconnect notice from New York Telephone, and three hate letters from Mademoiselle readers demanding to know just what it is that makes me think that I have the right to regard houseplants—green, living things—with such marked distaste. I call the phone company and try to make a deal, as actual payment is not a possibility. Would they like to go to a screening? Would they care to attend a party for a heroin addict?”

Writing, especially when you’re young, is one of those great professions where the more you do it, the broker you get. It probably isn’t the right way to live, but it’s how I live and how a lot of my friends live. There’s somehow never any money, but a lot of screenings and parties for heroin addicts. I grew up in New York, and even when I was young, I wasn’t young. I turned young at 22, when the city unfurled itself.

The train goes anywhere. The nights are a bacchanal, celebrating short films that miraculously aren’t short enough or art openings that are too packed to ever see the art. The days are exercises in escapism—trips to the Rockaways, or the Neue Galerie, or the Golden Mall in Flushing—tinted by the feeling of being one tiny cell in the city’s anatomy, and accumulating just enough small victories to feel like you possess the world.

The city’s pleasures are the sweet and secret purview of the young—eking out “regular” status in a restaurant or a bodega, walking down a street where you know everybody, yelling at bikers, yelling at drivers, yelling at pedestrians, exiting the subway station on the right corner because your internal compass is magnetically attuned to two rivers. New Yorkers are sentimental hypocrites. Fran understands this well.

People want Fran to tell them how to live because it seems like she’s figured out one of the most challenging parts: how to escape expectations—the world’s and one’s own. She’s an anomaly—a writer who doesn’t write (although, if I had to write everything by hand, I’d be an orator too), an evergreen icon who walks the streets of New York unencumbered, an anti-celebrity who’s managed to maintain relevance despite waging a decades-long campaign against the concept. She does what she’s always done, and the world envies her for it.

When a blue-haired girl in the Flatbush audience called out a question about legacy, Fran shook her head dismissively, offering a pithy, “I don’t care,” followed by, “If you’re worried about what people will think about you after you’re dead, you have other problems.” I’ve never been one for audience participation, so instead of asking a follow-up question, I choose to read between the lines: Spending your time on the hamster wheel worrying about being forgotten makes you no better than a rodent.

The human experience is an unending stream of small humiliations and miseries that culminates in The Big One. Doing something with your life can be as simple as going to dinner, making ends meet, walking the neighborhood, or talking with friends (with friends like Toni Morrison and Scorsese, Fran has had the upper hand here). Not everything has to be documented, it can just be said. If you take that as the baseline, you can go about the task of living with your hands free, leaving you prepared to seize a flash of good fortune.

As the question of legacy lingered malodorously in the air of the Kings Theatre, I thought, possessed by Fran’s spirit, What a stupid question.

Nicolaia Rips is a New York-based writer and the author of Trying to Float, 2016, a memoir about growing up at the Chelsea Hotel.

Pre-order CULTURED's Winter 2023 issue here.

in your life?

in your life?