Alexander Chee: I'm reading your new book, Johanna. I was struck by your author photo.

Johanna Hedva: First of all, I need to say I'm deeply indebted to your work. There are several sentences in your books that live in my head on repeat, like mantras that come back at the right time. While I was writing this novel, I relistened several times to the talk you did at Tin House that's now in the Between the Covers podcast because I was getting stuck at places where I was like, “What the fuck is supposed to happen on page 150 that's different than page 250?” You address those questions so specifically and eloquently in that talk and in your essay collection How To Write an Autobiographical Novel.

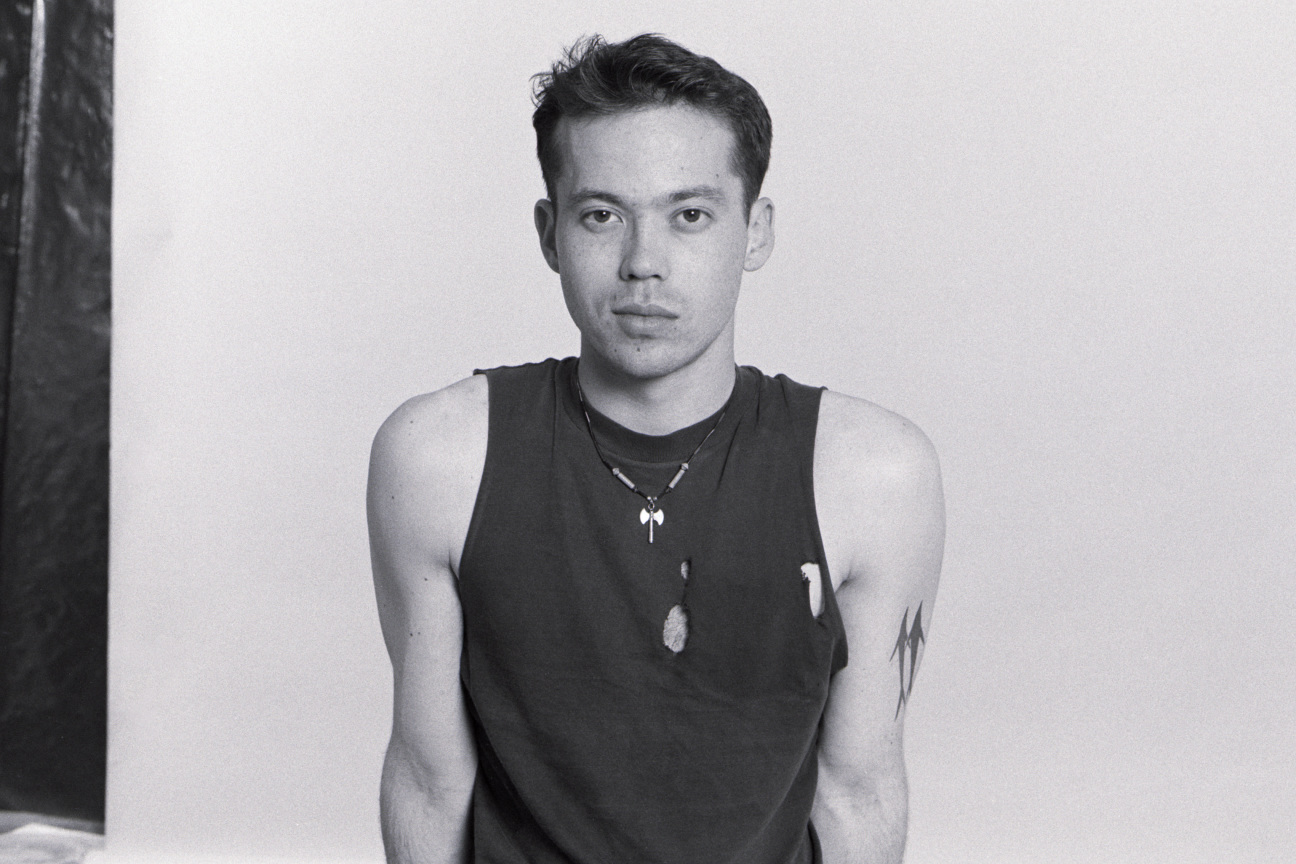

There’s a whole story with my author photo. When we were negotiating the contract, I knew we weren’t going to get final approval on the cover, but I told my agent, “I want you to make a big deal about it because I want it known that I'm that bitch about this sort of thing.” My undergraduate degree is in design, so I made a whole pitch deck of how I thought it should look—fonts, colors, which artists to commission for an image, the whole thing.

I really wanted us to go for a 1970s book cover design where on the back it was a full-bleed black and white author photo with no text, like Joan Didion and Susan Sontag’s. My editor said, “Well, take a good enough photo, and [then] we'll see.” Challenge accepted, bitch.

Chee: The portrait looks very artful. What was the planning that went into it?

Hedva: I wanted to find something between imperious twink and odalisque. The look is head to toe Rick Owens, and the shoes are very important. I always say that once I got the right shoes, everything fell into place in my life.

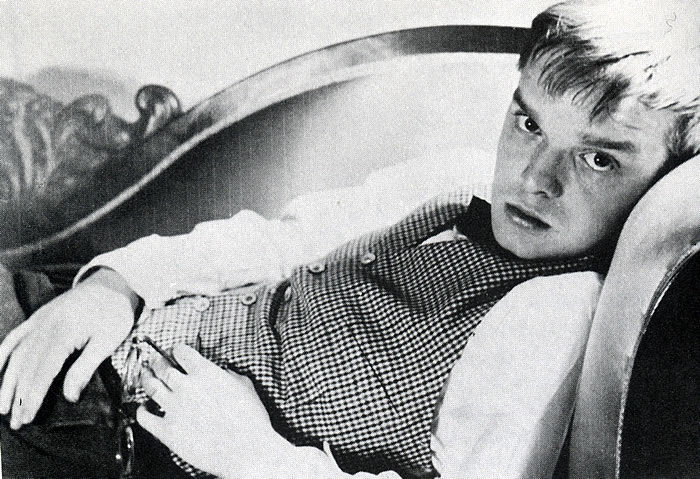

I sent a couple references, like the Truman Capote Other Voices, Other Rooms image. I obviously don’t look like a twink, but I would like to get as close to this Capote-twink-odalisque as possible. I also sent Anne Carson’s New York Times portrait where she's sitting there looking down at you imperiously, dressed like Oscar Wilde in a suit and a tie.

Chee: I met her once on the roof of the poet Mark Bivens’s building. He had thrown a party for her after a reading at the Dia Art Foundation. She was wearing a purple and teal velour jumpsuit. It looked like athleisure but for poets. We talked about novels and fiction, and even though she had just published Autobiography of Red a few years previous, she said she could never write a novel because she could never reproduce or imagine somebody else's intuitions. I thought, You actually did that pretty well, but I also felt weird contradicting her at a party. So I just let it go.

Hedva: I'm a disciple. I've listened to all of the interviews and podcasts she's done. I appreciate how she regularly dislikes her books once they're out in the world. She says she doesn’t want to do promotions but her publisher makes her. I wonder if that's part of her methodology. She's got a wry sense of humor, especially toward her own voice.

Chee: I read her essay “Kinds of Water” every year for 10 years. I first found it when I was a writing student in 1989, and I read it that way at least up through the publication of my first novel.

Hedva: Do you have other books like that that you've re-read regularly?

Chee: I teach Never Let Me Go [by Kazuo Ishiguro] a lot, and I still learn from it … I've read Voyage in the Dark by Jean Rhys over and over. The Passion [by Jeanette Winterson] was like that for me for a while. There was a boy who even used it as a part of this highly aestheticized and staged seduction of me, where he posed as someone who didn't know that it was my favorite novel, went to the bookstore where I worked, and asked if I knew where the novel was as a pretext to get me to talk to him … Jeanette Winterson got me laid, I guess.

This is making me think of my own first author photo story. I chose a friend of mine whose work I love. Part of why I chose him is that he did a big portfolio every year for Cosmo's teen magazine, CosmoGirl, full of all these hot hunks. I thought, Eric's going to make me look hot. I get them back, and I look like a writer from the ‘50s. I loved it, but it was ironic.

Hedva: For mine, I really wanted a duality where the front cover and the back cover were telling a little story unto themselves, which is why I pushed that we should not have back text or description, just images with the title. I kept thinking, Your Love Is Not Good, what is the image of a person who would say that line?

Chee: How demented do you want to appear?

Hedva: As demented as possible, but hot.

Chee: This is my headshot from a decade earlier. [Shows phone.]

Hedva: Oh, this one is hot. This is Grindr, sex on a stick. I’ve been on Feeld this year. It’s an app for the new horizon of queerness. There are 75 categories that people can pick on there, like hetero-flexible, gender questioning, bicurious, but often it's just a photo of an ostensibly straight man rock climbing. It's very confusing.

Chee: The fantasy coming from the generation that came out in the ‘50s and ‘60s was that, someday, we wouldn't even have to have a word for it. Instead, actually, we have decided the opposite: We want so many words.

Hedva: They are all meaningless. I came out in 1998, which I think was one of the last years you could be queer before the Internet helped to consolidate your identity. You had to know the day of the week to go to the gay night at the club. You had to go there physically and reach through the fog in the dark of the basement to find the body part you were searching for. There was something actually deviant about it. Now you can be on an app and pick from 75 categories. I just want José Esteban Muñoz to come back from the grave and explain this new horizon of queerness to us.

Chee: Back to your book… It has a nature of obsession that I call the “identification crush,” where you're wanting to fuck the person you want to be next or at least make them love you. It feels almost old-fashioned to read about obsession in this way, even though the novel also feels like a report from this reality. It makes me feel awake when I read it. How did you do it?

Hedva: It was a thought experiment where I began with the question, what if I start with a character who on paper, at the DMV, would have all of my same identity demographics: Korean father, white mother, born and raised in Los Angeles, very white-passing, poor as dirt, queer as fuck, into kink, went to art school, wanted to be somebody. But then, at every juncture where she has to make a choice, I wanted her to make the one that I disagreed with, ethically and politically, the one I did not do. I’ve been saying it’s an attempt at “anti-auto-fiction.”

Novels are very good at showing this distance between the interiority of a character and how that is read externally in the world, and that distance is political for some people. How I feel I am on the inside is not necessarily how I'm read on the outside with my body, my skin color, my race, and my gender. I’m someone who doesn't look like what I am. I look like a white, cis, abled woman, and what I am is a Korean-American, disabled, genderqueer person. I wanted that political distance to get juicy and messy and wet in my book.

Chee: Was it a gradual realization that you wanted to explore these concepts in the book, or was it more intentional than that?

Hedva: In the beginning, I had a couple of realizations about why all of my relationships with the women I had fallen in love with had failed. I was working through some shit around over-identification and the parasitism of queer desire in therapy. I was 30 and had just graduated from my MFA in art. I did not want to do commercial art at all. For my MFA in visual art, I wrote a novel.

That's the thing, part of me wanted to see if this main character chose correctly. She's making money and is successful in a way I'm not. I don't show in a gallery. I'm in the art world but not in the art world of the novel. I've never been to an art fair. I've sold three pieces in 10 years for, like, the high three figures. I wanted to explore the idea of a tragedy where you watch a character make the wrong choice because there is no other choice.

Chee: It makes me think of Anne Carson in Eros the Bittersweet, again. She talks about early Greek novels as experiences of paradox, and how characters find that they must do the thing that they absolutely cannot do but they must do it all the same … What are you working on now?

Hedva: My next book is a collection of essays called How to Tell When We Will Die: Essays on Sickness, Fate, and Doom. That comes out in 2024. I have a solo exhibition, If You’re Reading This, I’m Already Dead, opening in October in LA at Joan, a feminist, non-commercial art space. The other thing I’m working on is a new album. I wrote a bunch of songs on an acoustic guitar. I think the genre is succubus folk, or hag blues. I don’t know what it’s called yet, but I think "Fight Me" would be hilarious for the merch. What about you, Alex?

Chee: I love all these titles. I have been working on a short story collection that I initially called Rich Children and then Self-Defense, and a novel called The Weddings. It's sort of a comedy about gay marriage. It's about this queer man whose life changes once marriage is federal. And I had a sabbatical year thanks to the Guggenheim to work on another non-fiction book altogether. Right now, that book is called You Should Write a Book About Your Family, which is something my uncle says to me at some point in the book, early on. I don’t have an album, though. I'm a little jealous.

Hedva: I'll send you the "Fight Me" shirts once we make them.

Chee: Maybe we can have a one-time-only band called Imperious Twink.

Hedva: And the title of our mixtape is Highball. Oh, girl, I'm gonna start writing.

Your Love Is Not Good, published by And Other Stories, is out now.

in your life?

in your life?