Buck Ellison never met Edgar Prince, the former Evangelical engineer turned manufacturing tycoon, his daughter, former U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos, or the rest of the Prince family for that matter—though he likely knows more about them than he ever would through any fleeting type of social interaction. The infamous dynasty, which counts inciters of extremist crusades across the socio-political spectrum, has been both the subject and object of Ellison’s gaze for six years, a necessary turn given the visual artist’s complicated fascination with American privilege. Several artifacts of these years of research are in “Little Brother,” now on view at Luhring Augustine’s Chelsea location.

Born in San Francisco, Ellison picked up a camera as a teen. He studied German and art at Columbia University, where he absorbed the writings of Jane Austen, Virginia Woolf, and Edith Wharton—novelists who parsed and probed the social codes and customs of their eras —before receiving his Masters at the Städelschule in Frankfurt. The artist now lives and works in LA, where he studies and recreates moments from others’ lives—typically the wealthier kind—as if they were his own. Through the movie set-like productions where Ellison prescribes everything from the actors to the clothes they wear, the artist does not attempt to gloss over or rewrite the actions of his subjects. His tableaux, instead, are a study of the humanity behind their corruption, and a question to the audience if any sense of connection can be made. To do so, Ellison continues to burrow himself in documents, only now his materials have evolved from literary texts to encompass tax papers, too.

“I used sources that are available to all,” Ellison tells me of his deep dive on Erik Prince, Edgar’s only son and the founder of the private military company Blackwater. The contract mercenary now known as Constellis played a substantial role during the Iraq War—which began 20 years ago this week—most notably killing 17 and wounding 20 civilians without cause in Nisour Square, Baghdad. In 2018, Prince proposed a $5 billion plan to the U.S. government to privatize the war in Afghanistan; three years later he began selling emergency evacuation tickets from the country for $6,500 a seat. Prince, who now heads the private equity firm Frontier Resource Group after selling Blackwater in 2010, is one of the most reviled men in America.

“I found the most effective way to understand Erik was to look back in time,” explains Ellison, who, in addition to IRS forms, read Prince's book, Civilian Warriors: The Inside Story of Blackwater and the Unsung Heroes of the War on Terror, three times. He also interviewed game hunters and stable masters near the Prince family ranch in Wyoming, where “Little Brother” takes place. “Erik would be the first to tell you that private military contractors are nothing new,” Ellison continues. “I have read that corporations like the British East India Co. were created so that companies could pursue their goals by whatever means they deemed necessary, such as forming private armies and waging wars, without a single man having to take responsibility for actions.”

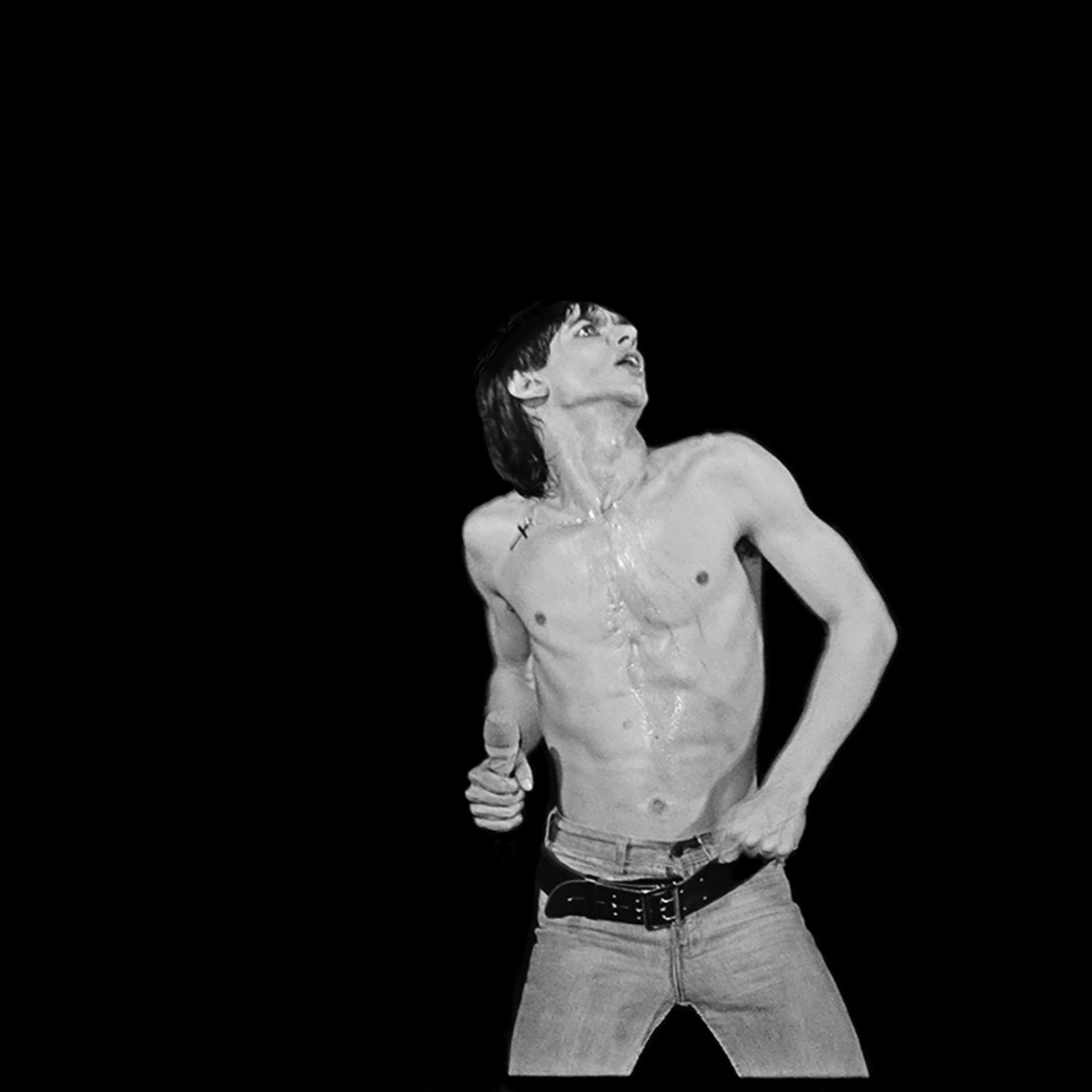

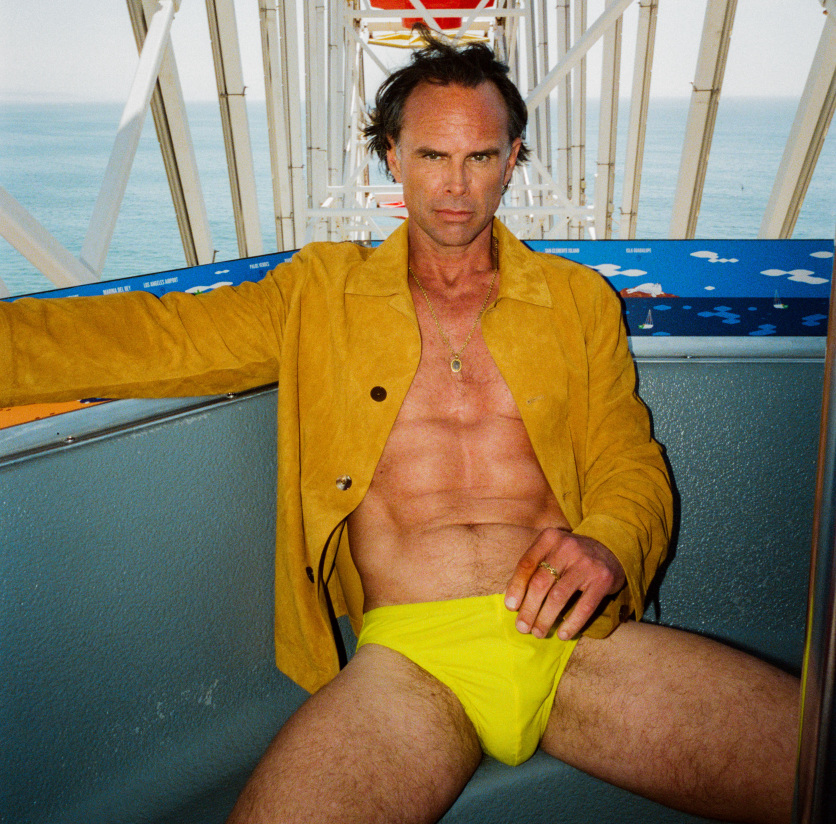

“Little Brother,” which follows Ellison’s previous studies on the Prince family, consists of six photographs and a film from which many of the vignettes are taken. One of the perplexing works on view, Fog, In His Light We Shall See The Light, Raintree 23 Ltd Ptnr, Excess Distribution Carryover, If Any, 2003, shows an imagined Prince in a rare scene of joy. Shirtless in what appears to be a laboratory situated in a horse stable, the actor playing him smiles before a working recipe of some kind of a biological concoction. Uncertainty looms beside relics of farm life and snapshots of leisure activities from the past. Are these ingredients for the world’s next weapon of mass destruction or a DIY solution for a common ranch problem? The viewer does not know. (And hopefully never will.) Another piece, After the Rain, $17 is how much Blackwater founder pays for a haircut, Paid-in or capital surplus, Hans, 2003, 2021, sits atop a unique wallpaper relief entitled Five Windows. “I was rummaging around in an office with five large windows, looking for some documents,” says Ellison, recalling the series’ comprehensive research process. The wall-to-wall on-site installation is a continuation of his analogy between Blackwater and the British East India Company. In its 19th-century heyday, the latter’s office was only “five windows wide,” but it “subjugated more than a third of the world’s people to produce opium poppies, tea, and silk.”

For better or worse, Ellison has intimately come to know Prince by reliving his life from afar. He describes the past six years as an attempt to understand “someone whose actions make my stomach turn.” Was it successful? The answer—for both the artist and the viewer—is buried somewhere deep, in the same puzzle of emotions that animates most of Ellison’s imagery. As the artist concludes, “it’s ambivalence, in the psychoanalytic sense of being intensely attracted to and repulsed by the same object.”

“Little Brother" by Buck Ellison is on view through April 29, 2023 at Luhring Augustine Chelsea in New York.