“About Time,” the title of Charles Atlas’s first career retrospective, now on view at the ICA Boston, is both a joke and completely serious.

On the one hand, Atlas’s work has always had a temporal focus, capturing the fleeting feeling of viewing live performance, the immediacy of personal interactions, the perma-scroll of TikTok, and the free association of thought. On the other, it is long overdue for a media artist of Atlas’s caliber—one who has been working for over five decades, basically invented the translation of contemporary performance onto screen, and has collaborated with the likes of Merce Cunningham and Marina Abramović—to finally get the retrospective treatment.

“He's been in three Whitney Biennials, he's received a special mention award at the Venice Biennale, his work is in the collections of so many major museums,” says the show’s curator, Jeffrey De Blois. “Yet he hasn't had this more concentrated celebration of his work and legacy.”

And that’s not because Atlas hasn’t been open to the prospect. For the past 10 years, he has been working closely with his gallery, Luhring Augustine, to find a museum that would be able to take on a retrospective of his work and the technical challenges it involves. This is especially complicated because his practice has evolved since the 1970s—from creating small-scale videos meant to be viewed on television monitors, to producing room-sized immersive installations that visitors can walk into and around. “This is really a huge order, there’s not many museums that could do it,” Atlas says, adding that the exhibition at the ICA Boston involves 31 channels of video, spread across four gallery-filling installations. These in turn draw on clips from some 125 works Atlas has created over his career, which he has digitized and remixed.

The show opens with The Years, 2018, an installation Atlas created to serve as a self-contained survey of sorts, featuring elements of 77 of his works, starting with his very first solo experimentations on Super 8 film in the '70s, Cartridge Lengths and Long Shots. These are presented in a slow, end credits-style scroll on four vertical monitors installed like futuristic tombstones, while a projected group of young girls look stoically on from above, like teenaged Fates, deciding his legacy. Atlas also published his own catalog with Prestel in 2015, with the help of Luhring Augustine, in which he reflects on his earlier work with characteristic frankness. The thouht behind these projects, Atlas recalls, was: “Well, if no one is going to do a retrospective, I’m going to do it myself.”

Delving back into his earlier work has become a crucial part of Atlas's practice for the past decade. “I'm hoping that when I finish this [retrospective], I can move forward again,” he jokes. MC⁹, 2012, for example, is a dynamic memorial to Merce Cunningham, the modern dance master who was Atlas’s close friend and first major collaborator. Atlas taught himself to use a Super 8 camera in 1970, at the age of 20, while working as an assistant stage manager for Cunningham's dance company.

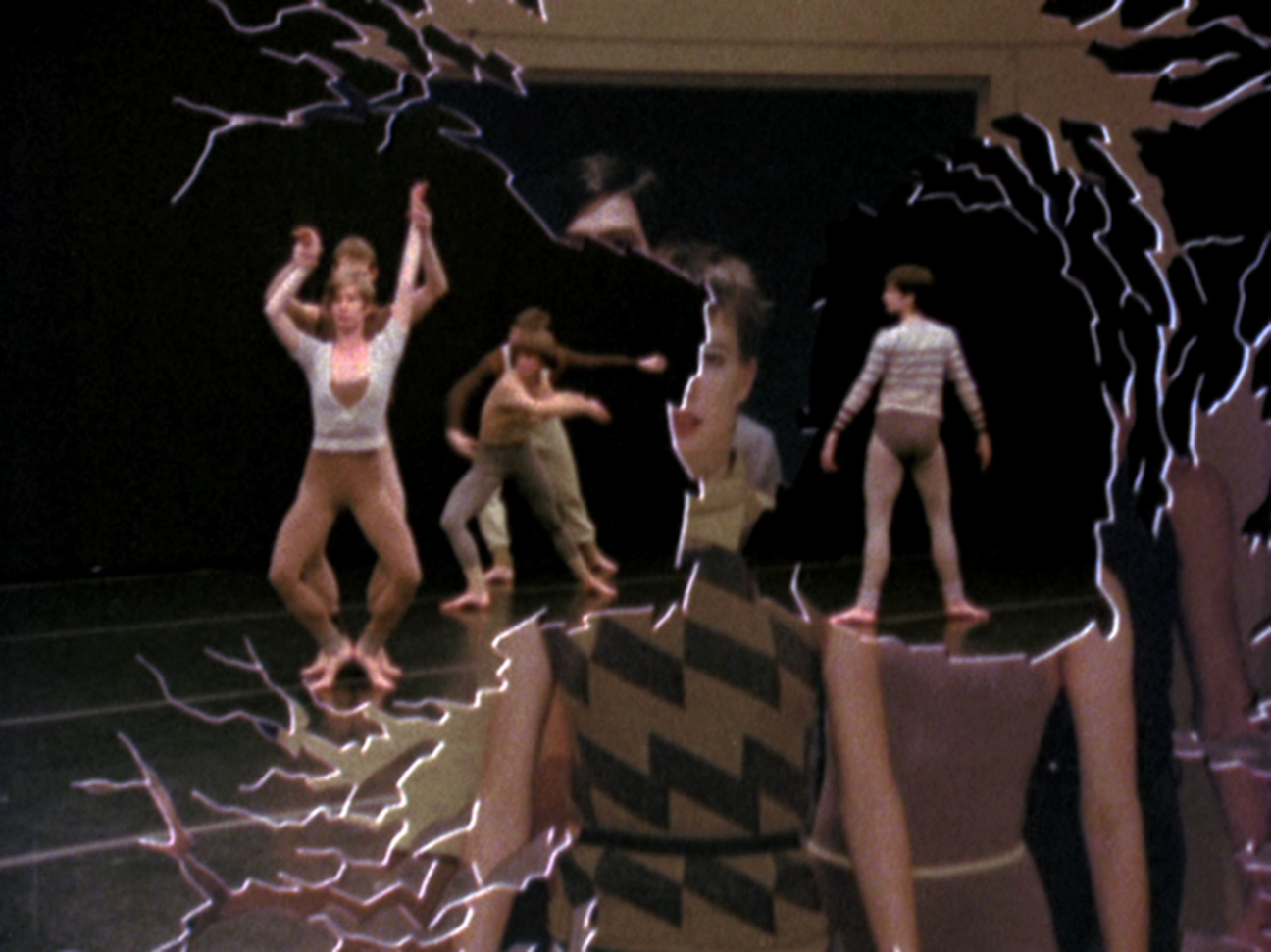

He created short films in his hotel room while on tour, and experimented with Cunningham and other dancers like Douglas Dunn in ways their movements could be transposed to film, starting with Walkaround Time, 1972, a recording of a dance performance inspired by the dawning computer age that featured sets and costumes by Jasper Johns. By the end of the decade, Atlas was the company’s resident filmmaker. MC⁹ features snippets from 21 videos made with Cunningham, including a personal moment in which the choreographer dances by himself to house music, filmed just before his death in 2009.

Similarly, A Prune Twin, 2020, revisits Atlas’s collaborations with the Scottish dancer and choreographer Michael Clark, including Hail the New Puritan, 1986, an “anti-documentary” that was commissioned for Channel 4 in the U.K. The installation—with another classic tongue-in-cheek title that is a partial anagram of the original—was created for a survey of Clark’s career at the Barbican in London. While the documentary on its own holds up remarkably well, encapsulating the anarchic energy of punk-era England, the installation with its multiple jumbo-sized screens positioned at different levels brings the characters and their movements to startling life.

“The context of my work has changed,” Atlas says of the expectations around video art, and maintaining visitors’ attention. “I didn’t want people to sit down and watch a thing in the gallery. I wanted to make a walk-through experience.” This instinct mirrors the way Atlas himself broke down the barriers between camera and choreography in his earliest pieces, moving in between and around the dancers when filming them, to emulate the sympathetic rush one feels when watching live performers.

“That's the fun part about some of the multi-channel video installations, they make you want to choreograph your own movements,” De Blois says. That effect is something that comes from Atlas’s decades of experience working directly on the stage, the curator adds: “He has a sense of theatricality, he understands lighting, he understands movement, he understands the proscenium stage, and the ways to disrupt expectations too. That all filtered into how he makes his work now. And that’s really unique and remarkable and specific to him.”

Atlas’s interest in film and performance dates back to his childhood in St. Louis, where, he told the curator Stuart Comer in 2011, “cinema was my escape outlet. I loved movies. I’m the perfect audience: I laugh, I cry, I cringe—whatever you’re manipulated to do, so cinema always had a power over me.” After dropping out of Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania, Atlas moved to New York in 1968 with the aim of seeing “every movie ever made” and he absorbed anything from silent films to the experimental works of Stan Brakhage. A stage-managing gig at an off-Broadway theater led to the opportunity to work with Cunningham, which Atlas jumped at because of the choreographer’s association with an artist he long admired, Robert Rauschenberg.

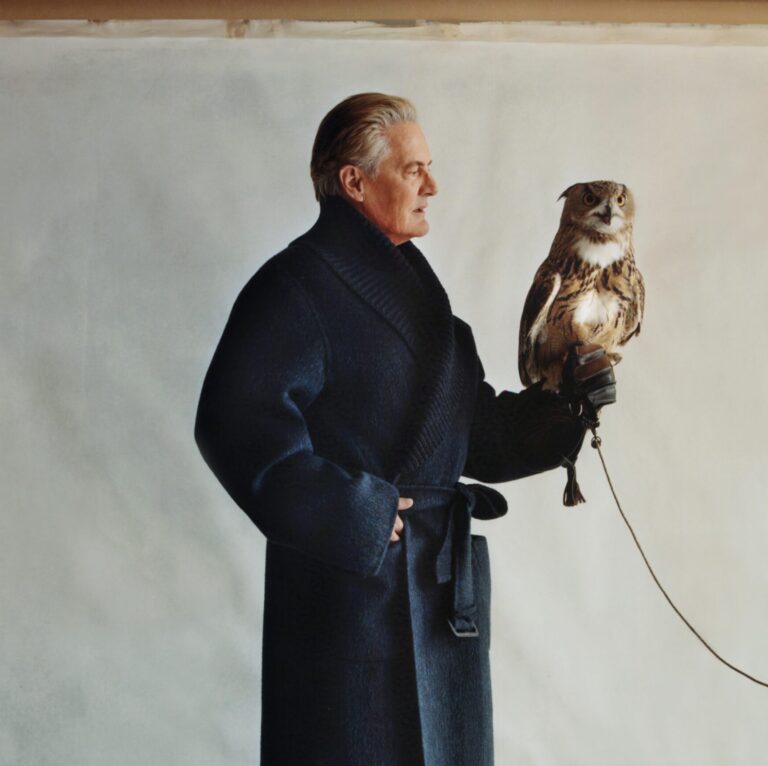

These kinds of personal connections have become a defining aspect of Atlas’s career, as can be seen in his newest installation created specifically for the ICA show, Personalities. This work from 2024 features video portraits of some of his famous collaborators who have also became close friends, such as fellow artists Marina Abramović, Leigh Bowery, Johanna Constantine, and Annie Iobst, as well as family, including his father, Dave Atlas, and his partner, the writer Joe Westmoreland. The work is presented on 12 monitors arranged on pedestals that form a spiral, in a gallery painted orange—Atlas’s signature hue, the color he dyes his sideburns—with wallpaper printed with screenshots from his 2003 project Instant Fame! at Participant Inc in New York, in which Atlas created live video portraits of gallery visitors.

Despite already having done the hard work of a retrospective himself, pouring over his back catalog with a critical eye and selecting the pieces he wants to redisplay, actually seeing all that work in a single show is a different experience altogether for Atlas. “I realized that I never showed more than one piece at a time. Seeing all these pieces together, it kind of just hit me, you know, that this is… it's big, it encompasses a lot of ideas,” he says, adding later in the conversation: “It's a little overwhelming to see everything from 50 years gone by.”

"Charles Atlas: About Time" is on view at the ICA Boston from Oct. 10, 2024, through March 16, 2025.

in your life?

in your life?