Upon entering the Whitney Biennial, you come face to face with a mammoth white flower printed on a black wall. The flower's circular middle, the pistil, has been carved out, creating a round door where viewers are invited to sit and watch Pollinator, 2022, an award-winning film by the New York-based artist Tourmaline.

The film begins with scenes of the artist walking through the Brooklyn Botanic Garden and the Edwardian period rooms at the Brooklyn Museum wearing looks by rising New York designer Claire Sullivan. These shots are then interspersed with recordings of Tourmaline’s father and archival footage of activist Marsha P. Johnson’s 1992 memorial service.

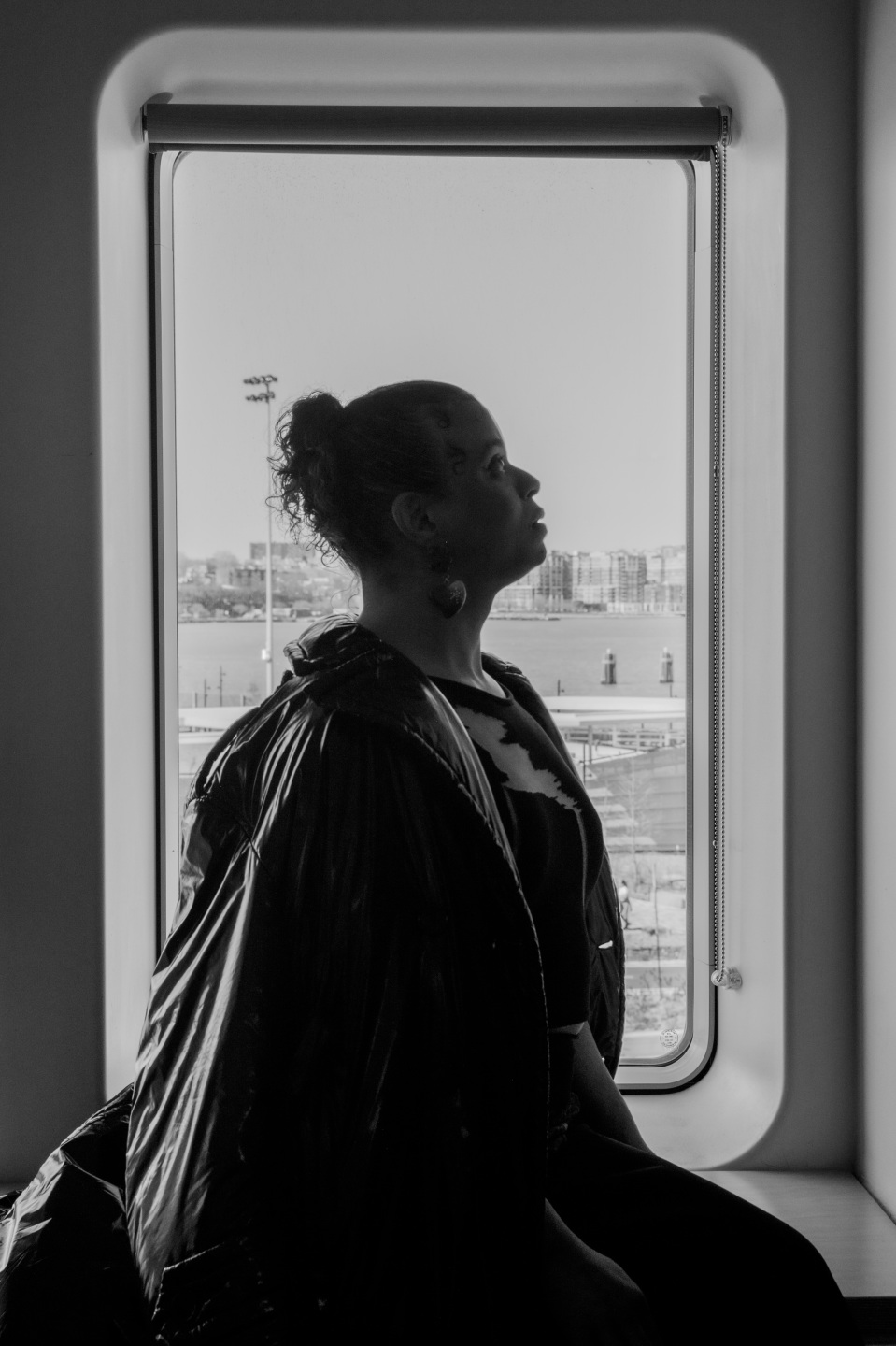

Johnson is a mother of the queer rights movement and a constant presence in Tourmaline’s life and work; she is currently writing Johnson’s highly anticipated biography. During the Whitney Biennial press preview, the two of us found a quiet place to sit, chat, and gaze at the Hudson River—another entity that, like the artist herself, looms large in queer history.

Adam Eli: Can you tell us what a pollinator is and how you use that term?

Tourmaline: Pollinators help move pollen from plant to plant, flower to flower, reproducing the beauty in the world. I feel there's nothing past tense about Marsha P. Johnson, my dad, or any of those who came before. Their most alive moment is playing out right now which means that Pollinator also has a spiritual component to it. It's about a sense of faith that people's essence, who they really are, transcends time and how, if we are open to it, we can actually feel how they're hanging out with us right now.

Eli: The film has scenes of Marsha P. Johnson's memorial, which is footage that I've never seen before. Most people don't know that much of the information about Marsha P. Johnson on the Internet is only on the Internet because you put it there. Where did you get this footage?

Tourmaline: I got the footage from my friend Randy Wicker, who lives next to the W Hotel in Hoboken, which you can see from right here. We can also see the Marine View Plaza in Hoboken, where Marsha lived for 10 years. Randy has been a friend of mine for maybe 15 years.

Eli: An icon.

Tourmaline: A true icon and was just celebrated as a grand marshal of pride last year. He was one of the first openly gay people to ever appear on television. Before [the] Stonewall [Uprising], he helped lead the sip-in at Julius Bar.

Eli: …which is the best gay bar in the city.

Tourmaline: Totally. Randy was on the cutting edge of pre-Stonewall activism here in New York. He had a lighting and antiques store, and before they were friends, Marsha would do her performance bit called “Spare Change for a Dying Queen” on the corner of Hudson and Christopher [Streets], which is exactly where his store was. Marsha had a powerful effect on Randy and really supported his upward spiral and realizing it's beautiful to be deviant. She taught him, and all of us, that it's beautiful to move beyond societal norms, to let those limiting beliefs go and really feel a sense of aliveness.

Eli: What was the memorial like?

Tourmaline: The memorial happened about 20 days after Marsha’s body surfaced right here in the Hudson River near Christopher Street Pier [in 1992]. It started at the Church of the Village on Sixth Avenue and folks marched down Christopher Street and ended right here [near the current Whitney building], where they pollinated the river with flowers and Marsha's ashes. To me, pollination evokes the sense of creating more. In that moment, Marsha's spirit was made available for more people to understand and be impacted by her. That’s the central reason the footage is in the film.

Eli: You recently performed the ritual of throwing petals into the water for our beloved Cecilia Gentili, another icon and mother of our movement. Can you tell me about how Cecilia, who also spent much time in this area, is present with you at this moment, on the eve of the biennial opening to the public?

Tourmaline: Cecilia, [ACLU lawyer] Chase Strangio, and I worked together at the Sylvia Rivera Law Project. We were organizing together around trans healthcare, around housing, around getting our basic needs met as a community. At the same time, she was writing, doing stand-up, creating art and fashion. It felt really powerful to see her light expand beyond any one arena and show that yes, we are showing up and showing out for our community members and yes, we're on stage talking about ourselves and yes, we're writing books.

She is at the forefront of what I do. I don't think there will ever be a moment where I'm not thinking about her, where she's not present in the work. I saw her last year in Miami, and she said to me, “This is my time.” Cecilia and Marsha had a lot in common. They were both performers, and they both exuded this sense of deviance and life. They organized around getting the basic needs for our community and for the rights of sex workers. They knew that this was, and is, their time. It is a powerful way to shape the world. They shaped my life, and they still do.

Eli: When you talk about the idea of Pollinator and what a pollinator is, it's almost like the textbook definition of Cecilia.

Tourmaline: Exactly. Cecilia lived the life of a pollinator and is still pollinating our world.

Eli: Another one of your films, Salacia, includes clips of Sylvia Rivera speaking on the Hudson Piers. What is your connection to the Hudson River and its piers? What is it like to show this piece practically on the Hudson?

Tourmaline: I started hanging out on the Christopher Street Piers when I was a teenager. A voice inside me just told me to go to Christopher Street. There were a lot of young people, some who aren't alive in the same way anymore. We used to hang out there despite the police trying to enforce a curfew at the time. There was a lot of pressure from residents of the neighborhood to “clean up” the pier, but we didn’t budge.

I was part of this group called Fierce that organized young queer and trans people of color right here in this neighborhood. I was looking for who came before, and wondering why we weren’t hearing more about them? In those moments, I started to hear whispers about Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson. There has been so much life here and it's important to make clear what was and to honor those that allowed for this space to be all it is now. We are turning up the volume in our own lives as a culmination of what came before.

Eli: The clothing in the film is done by Claire Sullivan, a collaborator of yours. Can you tell us about these looks?

Tourmaline: Claire and I have been collaborating since 2020. It's been so fruitful to have a sense of play, texture, and things spilling. The clothes feel really alive and they're tied to this lineage of people who used fashion to evoke self-determination, self-actualization and fun. For this piece, Claire had this brilliant idea of having handmade silk flowers that were sewn over the entirety of the costume that trailed along as I was moving through the Brooklyn Botanic Gardens.

That idea was really about, how do we evoke a sense of restfulness and replenishment while being as low to the ground as possible? How can we evoke moments of rest while also evoking the water, waves, and movement? She brings a level of insight into the now and into fashion history, which really elevates the work.

Eli: Yes, and she has all the technique, precision, and expertise of constructing a garment on a really high level.

Tourmaline: Exactly.

Eli: My final question is, if we're coming to the Biennial, what other pieces should we see?

Tourmaline: You have to see Tina Zavitsanos’s work. Tina is a very powerful artist. You have to see Carolyn Lazard's work. This is their second time in the Biennial, and they have a really powerful sculpture. You have to see Nikita Gale. My friend, Kiyan Williams, has a sculpture of Marsha, in addition to other sculptures, in the show. There's just so many artists in the show who I have really long admired and also known for over a decade.

“The Whitney Biennial 2024: Even Better Than the Real Thing” is on view at the Whitney Museum in New York through August 11. For more coverage of the Biennial, read CULTURED’s review and a roundtable discussion with the curators.

in your life?

in your life?