What exactly happened at Club Silencio in Mulholland Drive? How many alter egos does Lost Highway’s protagonist jazz musician possess? David Lynch—the acclaimed director of such and other cult-status films including Blue Velvet, Eraserhead, The Elephant Man, Dune, and Inland Empire—is a maestro of guiding his audience through the mind’s gnarly paths into the subconscious, plunging them into mysterious sequences of red curtain-draped dark stages and sexually-frustrated encounters.

But way before the Los Angeles-based artist came to craft his irreplicable cinematic style, he was a student at Philadelphia’s Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. In 1967, Lynch poured his perceptible and psychic visions of mid-century Americana angst into an animated drawing of six, eerily morphed human figures entitled Six Men Getting Sick. Decades after he debuted the four-minute-long animation for his graduation project, Lynch returned to the Academy’s museum with a solo exhibition of his work in drawing, printmaking, sculpture, photography, and painting in 2014. In recent years, he’s shown solo exhibitions at institutions such as the Bonnefanten in Maastricht, Netherlands, the Photographers’s Gallery in London, and the Garage Center for Contemporary Culture in Moscow, and last month he debuted concurrent New York exhibitions at Sperone Westwater and Pace Gallery, the latter of whom announced the global representation of Lynch’s studio practice.

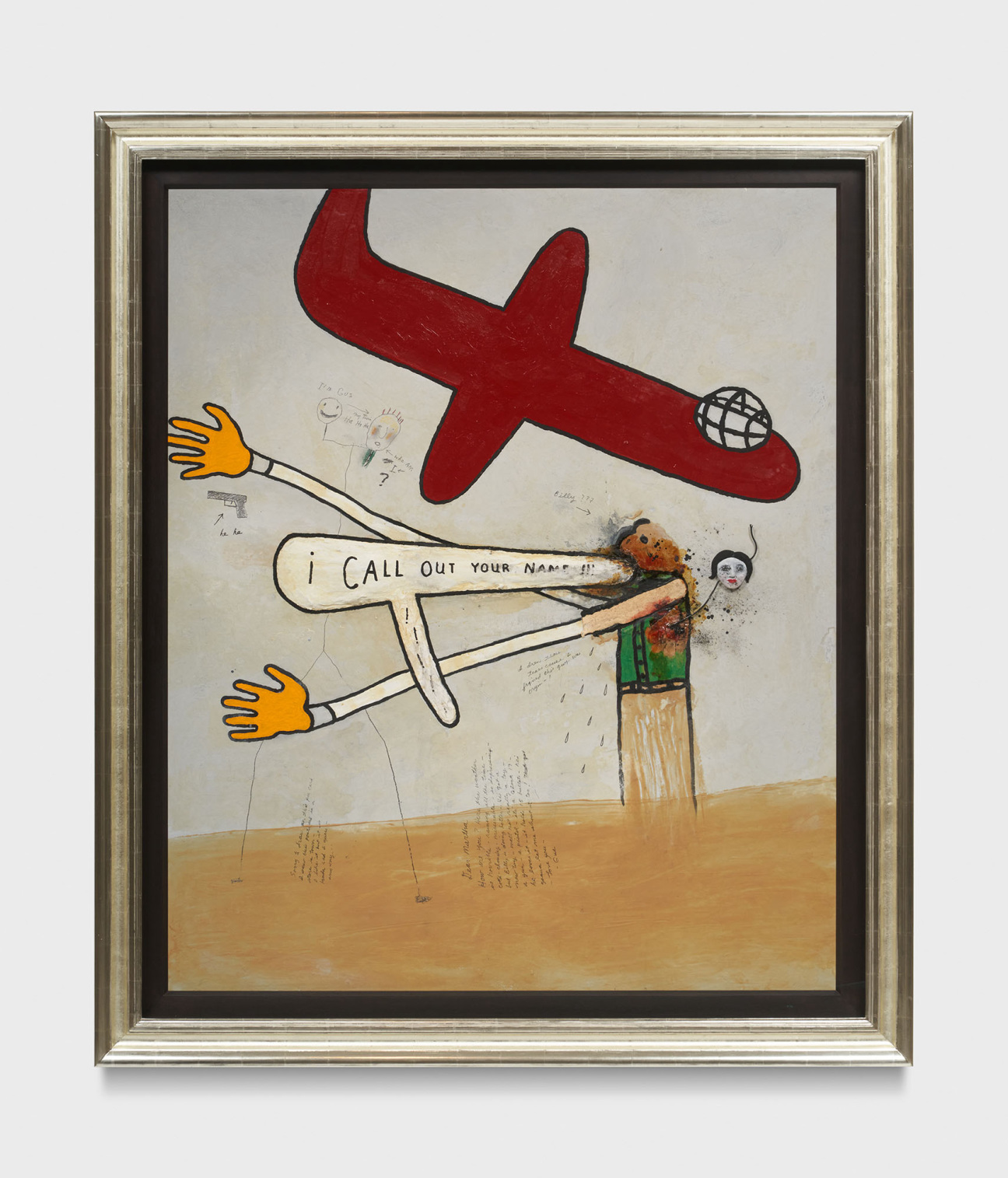

“His childhood, which was a very happy period in his life, is obviously still very present in his work,” says Kristine McKenna of Big Bongo Night. In his just-closed Pace show, new sculpture and drawing works by the artist meandered through introspective allusiveness while nodding to childhood whimsy. The exhibition embodied the insistently light-hearted crux of art that comes out of Lynch’s Hollywood Hills studio, and showed planes eerily hovering above child-like stick figures in mixed media drawings, and geometrically abstract steel and resin sculptures that hinted at the functionality of lamps.

McKenna—who co-authored Lynch’s 2018-dated memoir Room to Dream after a 43-year friendship with the artist—interviewed around 150 Lynchian collaborators for the title, and concludes that the connecting tissue between his work in fine art and cinema is “a duality—and a radio receiver-like awareness for both the light and the dark in the world.” While a binary is constructed through characters with shifting natures in his moving images—such as two femme fatales both played by Patricia Arquette in Lost Highway—Lynch’s art “reconciles with two extremes, beauty and violence with references to childhood imagination.”

Lynch’s oeuvre has other references, too. Brett Littman, who curated Lynch’s “Naming” exhibition at LA’s Kayne Griffin, and the gallerist Bill Griffin both note Francis Bacon’s influence on the artist’s depiction of the body as a subject of physical and emotional torment. “Painterly energy and occasionally disturbing aggressiveness are similar,” says Griffin, who has exhibited three shows with Lynch. The director of New York’s Noguchi Museum, Littman was already a fan of the artist’s film repertoire when he embarked on curating the 2014 show, but he felt compelled to investigate the illustration of the unconscious in his drawings and photographs: “David’s work changes the way we see the psychic underbelly of American suburbia,” he notes. The numbing sterility of domestic normalcy in Lynch’s films is often paralleled with similarly warped yet grotesque dream sequences, and fine art lets the artist push this medley to even darker territories on canvas.

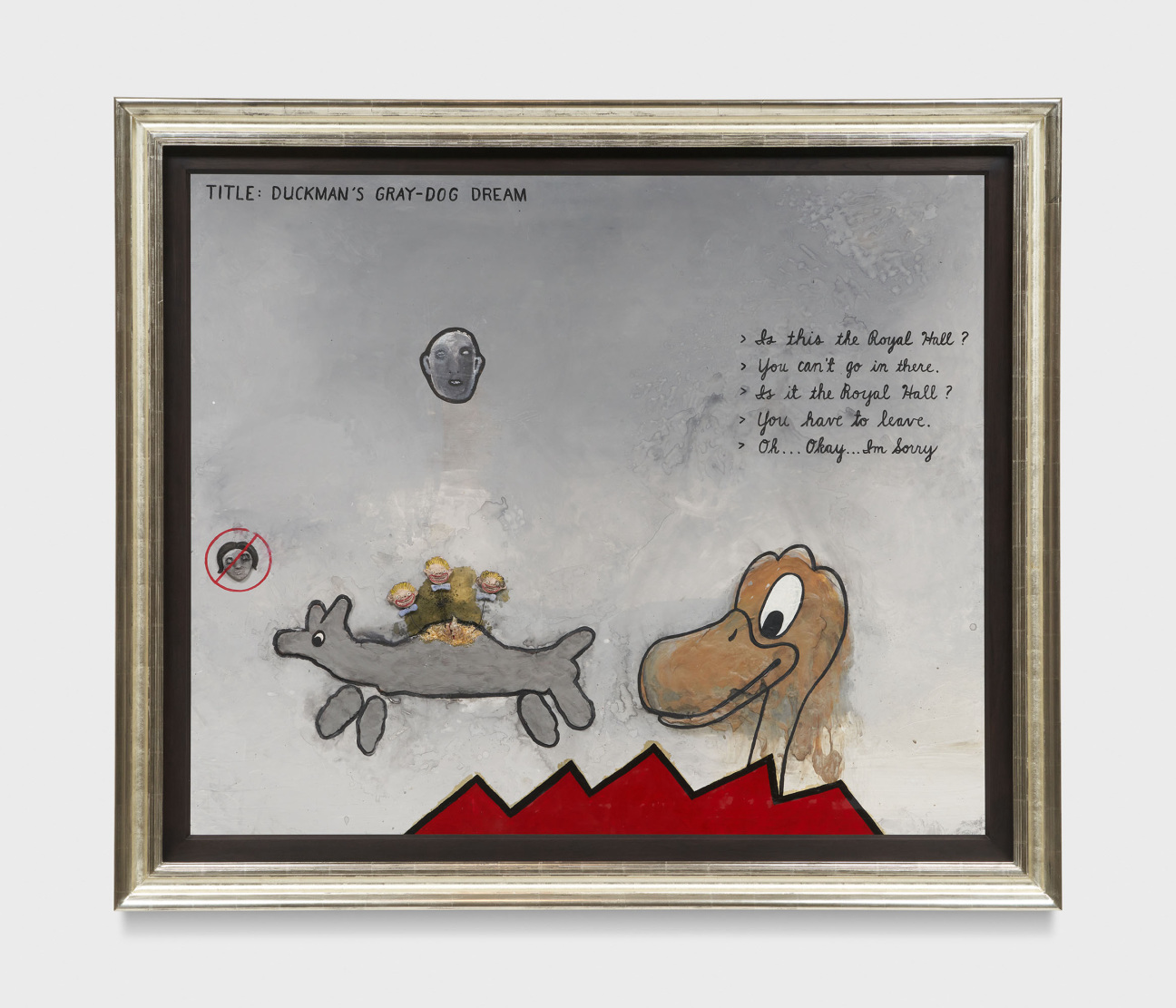

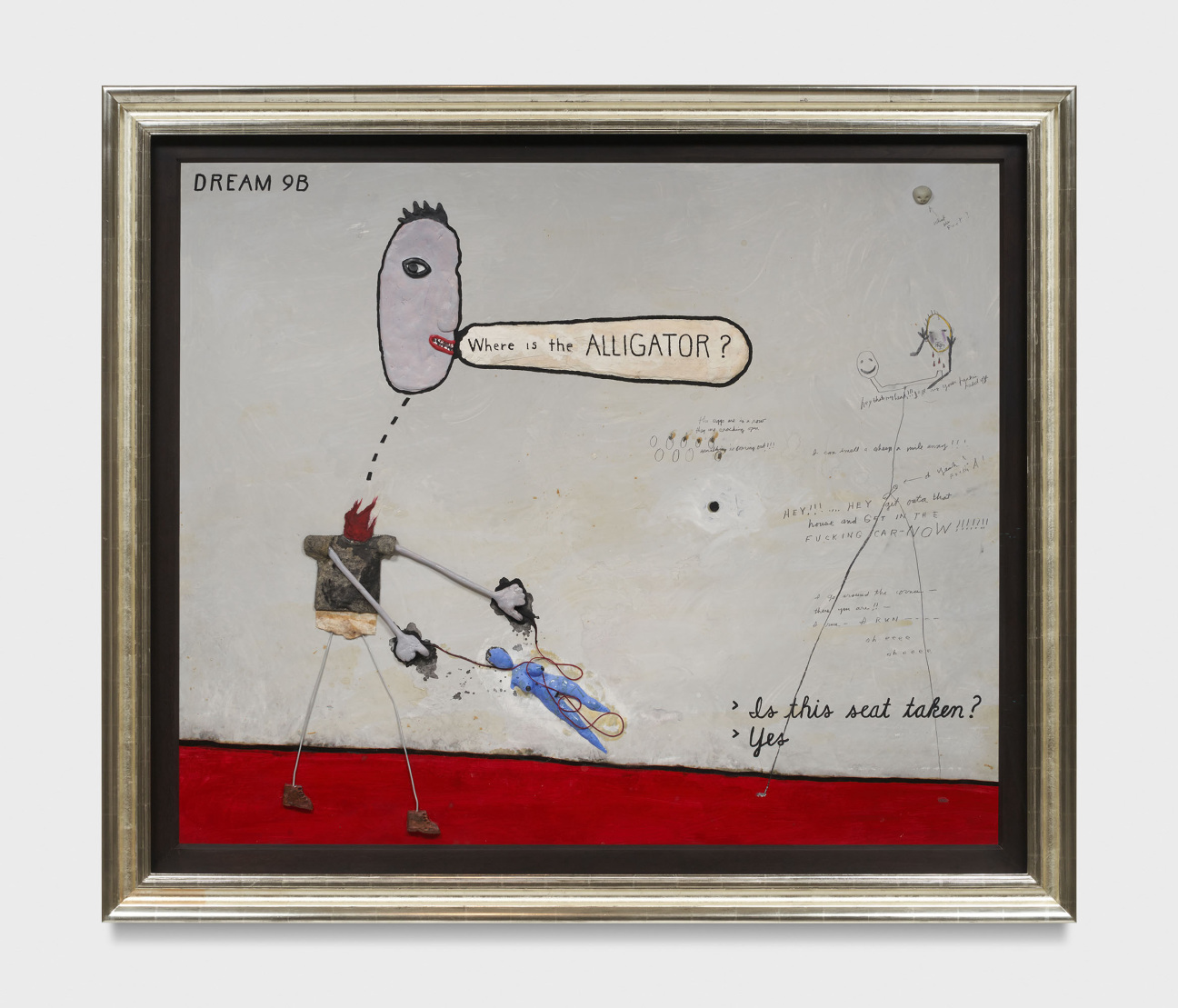

Lynch’s most recent works possess the inherent psychological complexity synonymous with his overall oeuvre. The work on paper or in three dimension imbues Bacon-esque markers of bodily existence into the narratives of the lipstick and blood-stained Hollywood glamour recognizable from his cinematic work. Duckman’s Gray-Dog Dream and Dream 9B: Where is the Alligator? (both 2022) recall children’s drawings yet they are veiled by the dizzying uncanny of dreams and violence. The watercolors in “I Like to See My Sheep” at Sperone Westwater depicted planes precariously hovering over suburban lands occupied by eerie tranquility and violence at once. Lynch created these works at Paris’s Idem printing press which had also inspired him to get behind the camera in 2013 for a documentary titled, Idem Paris.

“It’s about time,” McKenna says about the new attention on Lynch’s art, recognizing the hesitance among dealers to show the director during years past. “I am interested in ways art intersects into culture at large which is a case in David’s practice,” Littman adds. “Art for him is not a new phenomenon, but the galleries are now willing to cross over and support these activities by names established in other genres.”

in your life?

in your life?