Julian Schnabel’s home/studio/personal art gallery/family compound has a name: Palazzo Chupi. The renowned painter and filmmaker decided to add a few floors of a pink, Venetian-style palazzo to an old stable in the far West Village, outraging some and delighting others. Technically the grand building is a condo, but his son Vito is one of the few other residents, and I would guess that the committee deciding who gets in is made up only of a certain famous artist and nobody else.

The message is clear: It’s Schnabel’s world, people. We’re just living in it.

When I arrive to interview him on a clear fall day—a few weeks before a rare exhibition of his classic “plate paintings” debuts at the Aspen Art Museum—it’s clear he’s a little wary. Schnabel has been famous for a long, long time, and he’s won a Best Director Award at the Cannes Film Festival, so it’s unlikely that this hour we have together is going to be life-changing for him. And yet, when I make clear that I’m willing to look at paintings—to really look—Schnabel warms. He engages. Pretty soon, I’m helping him move big (and I mean really big, more than 10 feet across) canvases across his vast (and I mean really vast, cavernous, partially sky-lit) studio, to better see them. Some of these sprawling paintings, which all feature a huge stuffed white goat, reference his friend the late artist Mike Kelley.

“People can’t see paintings,” he says, moving around the room to assess his own work better. “There’s a certain light you need. I remember a quote: ‘Once a painting becomes familiar, it’s too late.’” It becomes clear that Schnabel thinks a lot about looking at art, about experiencing art. Later he says, “The first time you see a Caravaggio painting it’s amazing. The second time you see it is still the first time you see it. And so is the third time. And the same is true of the movie Shoeshine by Vittorio De Sica.” Bringing up film is telling. This is a guy whose movies—Basquiat, Before Night Falls and The Diving Bell and the Butterfly—were all defter and more realized than the work of many full-time directors. But Schnabel admits he’s annoyed that some people ask him, “Hey do you still paint?” His reaction: “I think, Where have you been?” he says, smiling.

The Aspen show brings him, and us, back to his core passion. “It’s the first museum exhibition to focus on these works,” says the museum’s director and CEO, Heidi Zuckerman, who had the clever idea to stage it. “How do you look at something with its own mythology around it but see it fresh?”

Good question. The show runs through February 19 and features 13 of the works that caused quite a stir when Schnabel started making them in the late 1970s. Created with actual pottery shards, they had an ancient aspect to them, and straddled the line between painting and sculpture. They didn’t look like anything else around—and still don’t today, “They have a kind of urgency,” says Zuckerman. “They make me uncomfortable,” which she means as a compliment. They don’t soothe, they provoke. Love or hate them, you can’t ignore them.

Schnabel has told the story many times, but in essence, the genesis of his most famous works was simple. “I tried to make a painting I hadn’t seen before,” he says. A trip to Spain, particularly his communion with Antoni Gaudí’s ceramic-studded works in Barcelona, planted the seed. “I thought, What if those colored shards in the benches were white?” As he leafs through some of the works on the Aspen checklist, it’s clear that these are his children and reuniting them will be an emotional experience for him. “This particular painting has been in Des Moines Art Center for 20 years,” he says of The Death of Fashion (1978). “I don’t get to see these very often.”

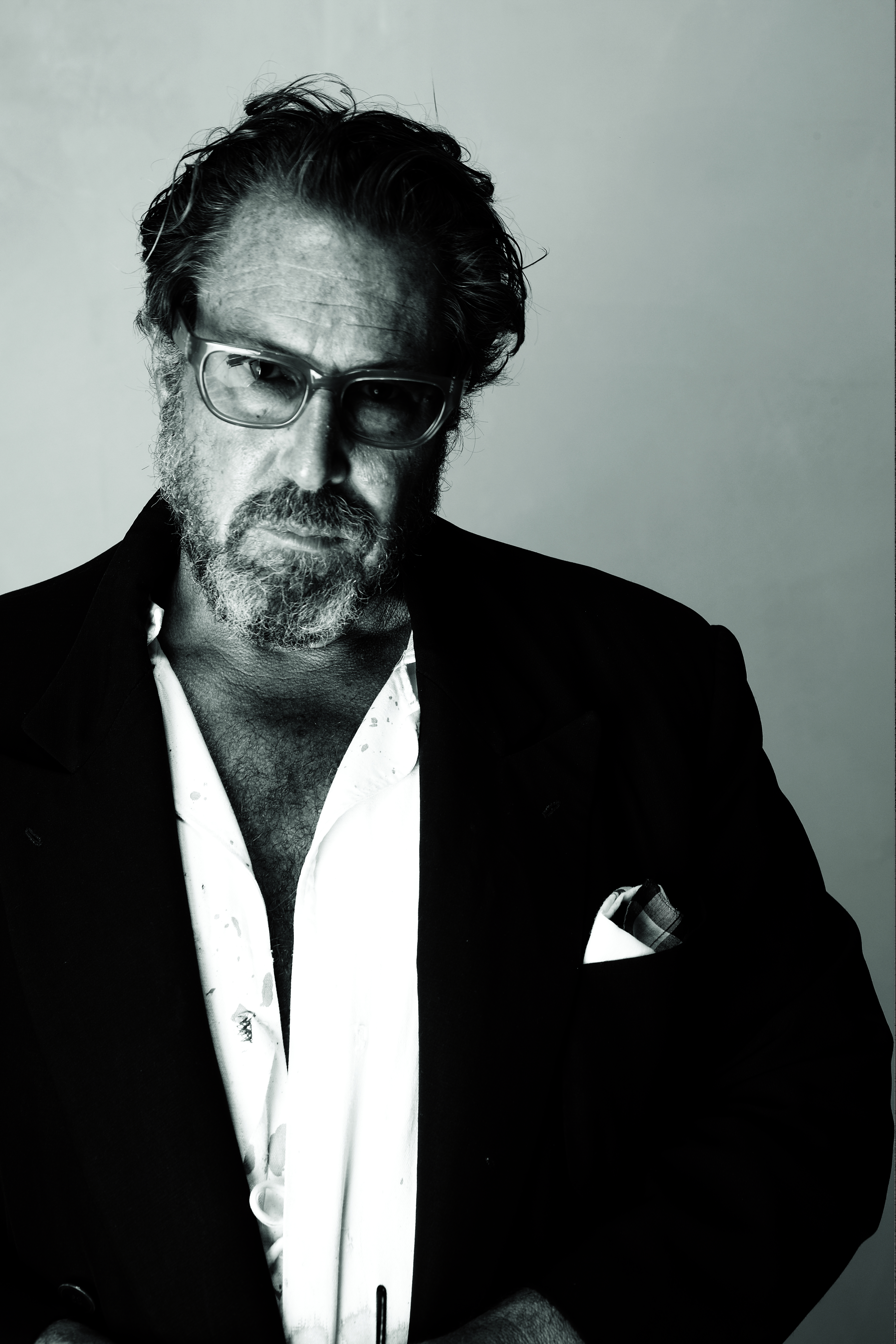

Schnabel, that famous bad boy of the art world, is now 65, and that enforces a certain perspective. “It’s a good thing,” he says of the show’s bringing the works together. “As you get older, you get more and more removed from everything.”

I’ve always thought there was a Pompeiian flavor to the plate paintings, and that Schnabel was making a comment on the long arc of art history—the fact that millennia after paintings have melted or turned to dust, ceramics will still be around. “There’s an archeological aspect in a way,” he tells me. “But that’s not the end-all, be-all. It was more like, What is the substrate of time? It’s about the signifiers that the plates have, the familiarity and the scale of them. As a painter, you look for all the multiplied possibilities of what a mark can do.”

Schnabel has a very bird’s-eye view of his project. “They figured into something that represented my whole pursuit—there was a battle between what the object was and a picture,” he says. “Where those two things converged, that’s the space where I was working.”

And it’s where he still works. Schnabel takes me in an elevator to yet another floor of Palazzo Chupi, into a warmly wood-paneled space that he uses as a personal gallery, and it’s filled with new canvases. I’m sworn to secrecy about what they entail, but you may see them at Pace Gallery next spring. They may—or may not!—take another very famous painter as inspiration. Schnabel stands back to drink them in, then leans forward to get a micro-view of their surface.

This is where he lives. Schnabel tells me matter-of-factly that, for him, “Painting is like breathing.”