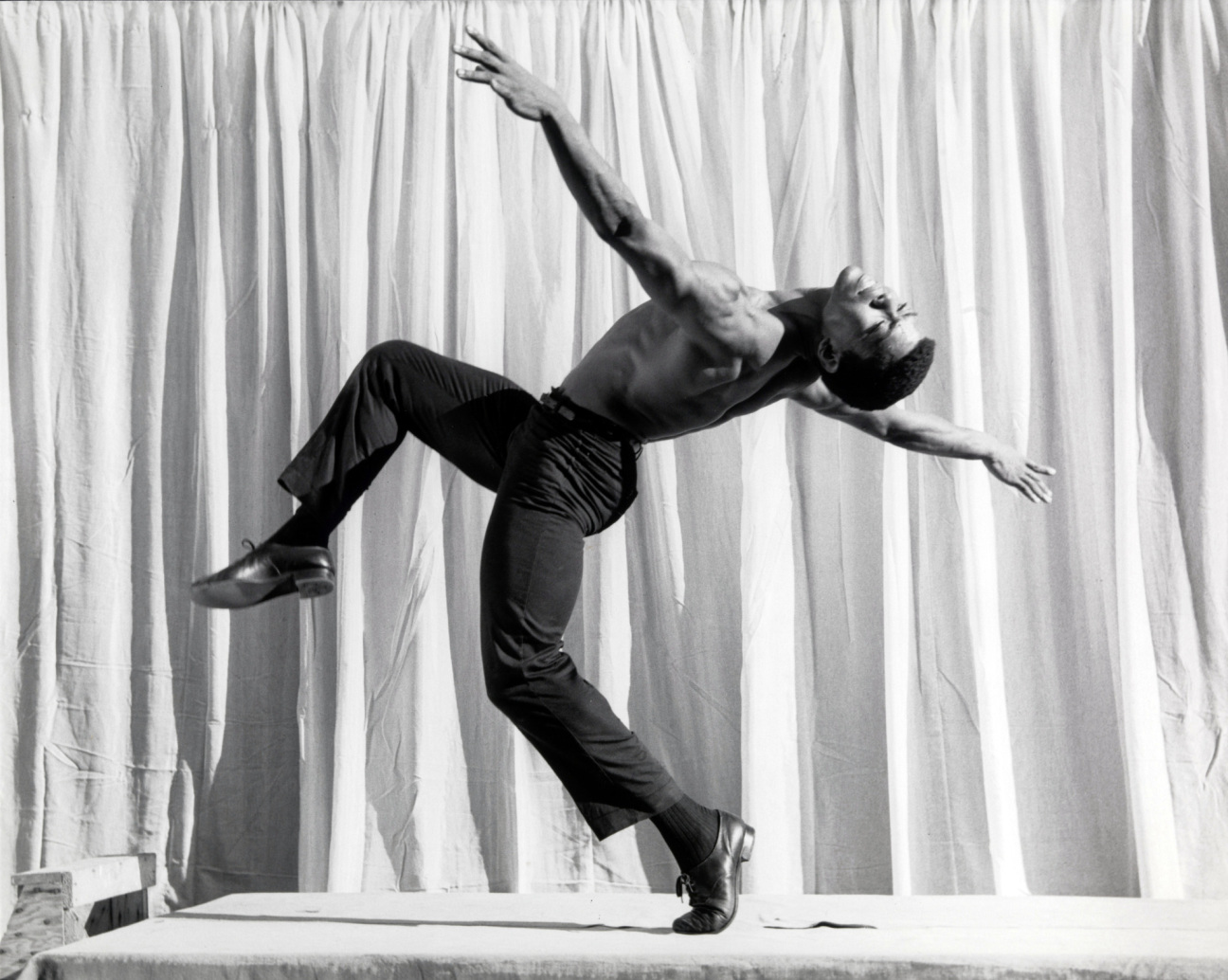

I met Adrienne Edwards, the Whitney Museum’s associate director of curatorial programs, last fall in Paris, where we went to see a performance of the late Alvin Ailey’s Revelations. A seminal work in the history of modern dance, it sees the legendary choreographer chart the course of Black history in America, and when we arrived at the Palais des Congrès, the venue’s 3,700-seat amphitheater was already packed. During intermission, the dancers extended a warm welcome to Edwards backstage, where they were eager to sing their praises about “Edges of Ailey,” her recent Whitney exhibition on the luminary’s life and ongoing legacy. The experience was “humbling,” she told me afterwards.

“Edges of Ailey” was a polyphonous portrait of a single man set against the much larger context of Black cultural production: the spiritual practices, musicians, writers, and artists who influenced his work and those he influenced in turn. Ailey’s personal ephemera was shown alongside video installation, music, live performance, and the work of 82 artists, including sculpture by Senga Nengudi and newly commissioned paintings by Mickalene Thomas. The fruit of six years of research, the exhibition's immersiveness and (literal) lack of boundaries are emblematic of Edwards’s curatorial style—one that ignores separations between disciplines, honors history while breaking traditions, and stokes the cerebral (with references to queer theory, Derrida, and more) alongside the visceral and emotional. Following the end of its four-and-a-half month run in February, Performa biennial founder RoseLee Goldberg attested to its power: “It’s really the only exhibition I can think of where people were almost in tears as it was coming down.” “It’s hard to be poetic without seeming capricious, or scholarly without boring our audiences,” added Whitney director Scott Rothkopf, “but Adrienne can do it all.”

At the opulent marble bar of a Paris hotel last October, Edwards wore a sleek all-black suit and a sparkling cuff on her ear and spoke warmly, describing how her own “disciplinary disregard” was influenced by the work of artists who refused categorization. Her exhibitions have focused on such genre-defying subjects as jazz composer Jason Moran, whose traveling solo show Edwards originated at the Walker Art Center in 2018, including his collaborations with artists ranging from Stan Douglas to Joan Jonas to Carrie Mae Weems. Edwards joined the Whitney later that year and, in 2019, worked with the famously reclusive David Hammons to commission new work by jazz composer Henry Threadgill. Performed alongside a flotilla of water canons, it provided the appropriately spectacular groundbreaking ceremony for Day's End, Hammons’ monumental sculpture on the Hudson River.

Most remarkable in Edwards’s curatorial innovation has been her capacity to capture the energy of performance inside a museum, even in the artist’s absence. “You can never replicate the live experience, so you have to get as close as you can to a feeling of it,” she told me, explaining how she conceptualizes an exhibition as a performance or installation of multiple sensory registers. “Just because we’re credentialed to be a curator or write a book, we don't have the right to bore people.”

Before the Whitney, Edwards cut her teeth commissioning works for Performa, where working with artists on the actual production of their works offered great insight into what could be executed inside a gallery. She might conceive of an exhibition during a performance; for example, she curated a 2020 exhibition for the performance art collective My Barbarian as a two-hour movie, where different videos were hung alongside the ephemera that went into them in an animated display of changing lights. Citing the 2022 Whitney Biennial “Quiet as It's Kept,” which Edwards co-curated with David Breslin, longtime friend Julie Mehretu noted, “The way you moved through the space and the different types of artists that were included is a testament to her unique form of thinking.” The exhibition's two floors were designed for fluctuating sensations of expansion and compression, with works—like the repeated assembling and dismantling of Jason Rhoades's 2000 sculpture, Sutter's Mill—meant to evolve and change over time.

I asked Edwards about negative reviews of the most recent Whitney Biennial that, to me, had read as a backlash against identity in the art world. We agreed that the work of white male artists like Rhoades, Paul McCarthy, and Mike Kelley were always deeply invested in their own identities. “They’re just never talked about in that way,” she said, the warmth of her voice firming very slightly. When I asked what she thought the next four years might bring, she sounded disappointed but undaunted. “American culture is very much about linear notions of progress, and I just don't think time works that way.” It’s more of a spiral, she added. “We come back around to times that have never left.”

The subjects of Edwards’s projects are often ones “that have been important and impactful to her for her whole life,” according to Mehretu. Growing up in Atlanta and South Carolina, the curator’s passion for performance began with dance at a young age. “I did all of them: ballet, tap, modern, jazz,” Edwards said, remembering the Ailey performances she watched as a child, and the community theater she did in high school. She earned a master's in Italian Renaissance painting at Seton Hall University, laying a solid foundation of art historical conventions, before earning her doctorate in New York University’s performance studies to diligently break them down.

“I was trying to write and think differently about what artists were doing in a much more rigorous and profoundly interdisciplinary way,” she said, focusing on where poststructural thought and conceptual art intersected with Black studies. She had a specific interest in “how Black artists, in particular, have fought against and avoided hyper-visibility,” poet and theorist Fred Moten told me, citing the violent history of repression and surveillance “that relegated Black folks to always to be watched, always to be seen and overseen.” Edwards’s 2016 Pace show “Blackness in Abstraction” was seemingly an antithesis to hyper-visibility, presenting a multi-racial group of conceptual artists and thinkers using the color black in terms of opacity, obfuscation, and darkness. Releasing Black artists from the onus of figurative representation, as she wrote of the exhibition, she presented the color in its broader potential: “black as a material, a method, a mode, and/or a way of being in the world.”

“What's really cool about Adrienne is that she’s ‘beyond category,’” Moten added, invoking a favorite compliment of Duke Ellington’s. “She really blurs the distinction between curator, art historian, performance studies scholar, and artist.” At the Ailey show at the Whitney, he felt like he was “moving through someone's brain.” “It was partly Ailey’s, and partly Adrienne’s too.”

Despite the fact that her own curatorial output often feels more akin to a stage production than an institutional exhibition, Edwards is reluctant to call her vocation an art form. “It’s important to know where the curator ends and the artist begins,” she said, before admitting, “but I do think there’s an artistry to it.”