Art’s lineage often reveals itself in the gravitational pull between mentor and student—a sentiment felt profoundly in Sebastian Gladstone’s Los Angeles gallery, where a new exhibition opens on April 11. Pairing the late painter and University of Washington professor Denzil Hurley with his former student Brian Sharp, the show is organized by another of Hurley’s protégés: the prominent artist Jonas Wood.

Hurley’s quiet yet rigorous approach to painting—a practice that began in Barbados and later flourished at Yale in the late 1970s—found its most enduring legacy in the classrooms of the UW. There, his monochromatic, meditative canvases and unwavering dedication to craft influenced a generation of emerging artists, among them Wood, Sharp, Kara Walker, and Hunt Slonum.

Sharp’s work, with its layering of everyday observation and abstract suggestion, reflects an open-ended conversation between teacher and student, carrying forward the values he first absorbed under Hurley’s guidance. In this conversation, Wood and Sharp offer a candid glimpse into that shared history: nights spent in the studio, intense critiques, and the lessons that still shape their work today. Their dialogue underscores how influence transcends individual style and how the effects of mentorship can endure long after graduation.

Jonas Wood: You and I met in 2000 when I started my first year of grad school at the University of Washington [UW], where Denzil was then teaching. I found out about the University of Washington from Nick Ruth, my undergrad painting and drawing professor. He was one of Denzil’s students at Claremont Graduate University. Nick said, “You should study with my professor, Denzil.” Being told to go somewhere because of how good of a teacher you are means something. But it is truly what Denzil’s always been all about—his relationship to teaching and his students, and his relationship to his studio practice. That is ultimately why we’re here talking and painting 20-plus years later. I remember my first impressions of meeting you, Brian. We became fast friends. What do you remember?

Brian Sharp: I remember you being super enthusiastic about everything; you just wanted info. Because I was a studio major in undergrad, I brought stuff with me. I knew a lot of contemporary art, so I remember us talking about that. You wanted to work—we both did. I feel like we really connected in the evenings… we’d stay and work into the night, take breaks, and talk about hip-hop, painting, and sports… You came in and started cooking right away.

Wood: It really was all about the process of painting—unwrapping the mystery that is “painting and drawing.” We really focused on the connection between them and the process of how one would go from an idea to making the painting. Denzil definitely made a huge impression on me, on you, and on many others.

Sharp: I remember thinking, “This guy is serious.”

Wood: [Laughing] This dude is serious as fuck… about painting. But about everything, I guess.

Sharp: There were times when he would laugh, usually about things he said himself. I really liked that part of Denzil; it was a soft part of him because, as a professor and as an instructor, he was so serious about making art and painting.

Wood: Yeah, let’s talk about Denzil’s work. When we were at UW, Denzil had this incredible installation of paintings up at the Henry Art Gallery, the university museum. It was a floor-to-ceiling grid of all these individual paintings of dots, slightly off-center. Beautiful. It turns out that he worked on those for years and years. He was very slow and meticulous and worked on things for a long time.

Sharp: It seems like his studio focus was certainly about tension, and repetition versus variation. I think the panels were different sizes, maybe two different sizes. The grid was laid out with like—

Wood: All the dots were kind of lining up, but the seam lines were a little bit off.

Sharp: Exactly, simple math, but complicated understanding. Seemingly simple compositions but complicated viewing, with levels of tension.

Wood: It was wild, and we were all mesmerized by it. This was our professor, and he was showing it at the museum. Denzil had a very assertive, smart, and intuitive teaching style where he challenged us to keep thinking.

Sharp: Totally. His vision wasn’t singular.

Wood: He wanted to take what you thought you knew and turn it upside down while still investigating that very thing. He wanted to shake you up in your core… Denzil also taught undergrad classes, like that class our friend Chris Dunlap took, “the box class.” Long story short, you’d make a box out of cardboard, about 20 x 24 inches, and you’d paint the box one color. Then you’d make a painting of that box, learning how to slow things down and figure it out. Next, you’d put things inside the box and make a painting of that. Then, finally, you’d deconstruct the box and make a painting of that.

Sharp: The level of seriousness with which the students approached that project was sacred. That was some metaphysical stuff. I know from Chris [Dunlap] that it really stuck with him. The idea was to keep going on whatever path the painting takes you. To find comfort in pushing through something.

Wood: Right, because it was such a simple idea. You’re dealing with line, color, shape, and that’s it. After grad school, we both kept in touch with Denzil. Did you see any of his shows in person? What were your impressions?

Sharp: Yeah, I did. I happened to be in New York for one of them. The show made me excited. The work was so open that it caught me. I found the direction he took the work inspiring. I took in Denzil’s paintings formally, they were reductive but electric, I never thought to plug any content into them. Looking back, evolving as a human and as an artist, I can see how this may have been naive. The work is elegantly open, interpretations seem welcome but not necessary.

Wood: It didn’t need to have any given narrative. I think it was all about—

Sharp: It.

Wood: Yeah, it. Having a reaction to it. I mean, you paint incredible abstract paintings. I paint figurative and representational paintings, but I think about it in the same way. The things that stuck with me are the philosophies about approach and rigor. What sticks with you the most about Denzil and painting?

Sharp: We once talked about luck, and I knew it was a word I wanted to work against. I didn’t want to be lucky. Maybe I was making work that looked like art… I was looking at a lot of art. But I was working around notions of what a painting could be, and I got uncomfortable with that idea. It forced me to narrow my focus, and I kept it that way for a couple of years. I had cornered myself, and I felt a responsibility to tie it up. When I did, it opened my practice intensely. It makes me think now it was just a journey I had to go through to understand what I was after, which I’ve come to describe as a sensibility instead of a style.

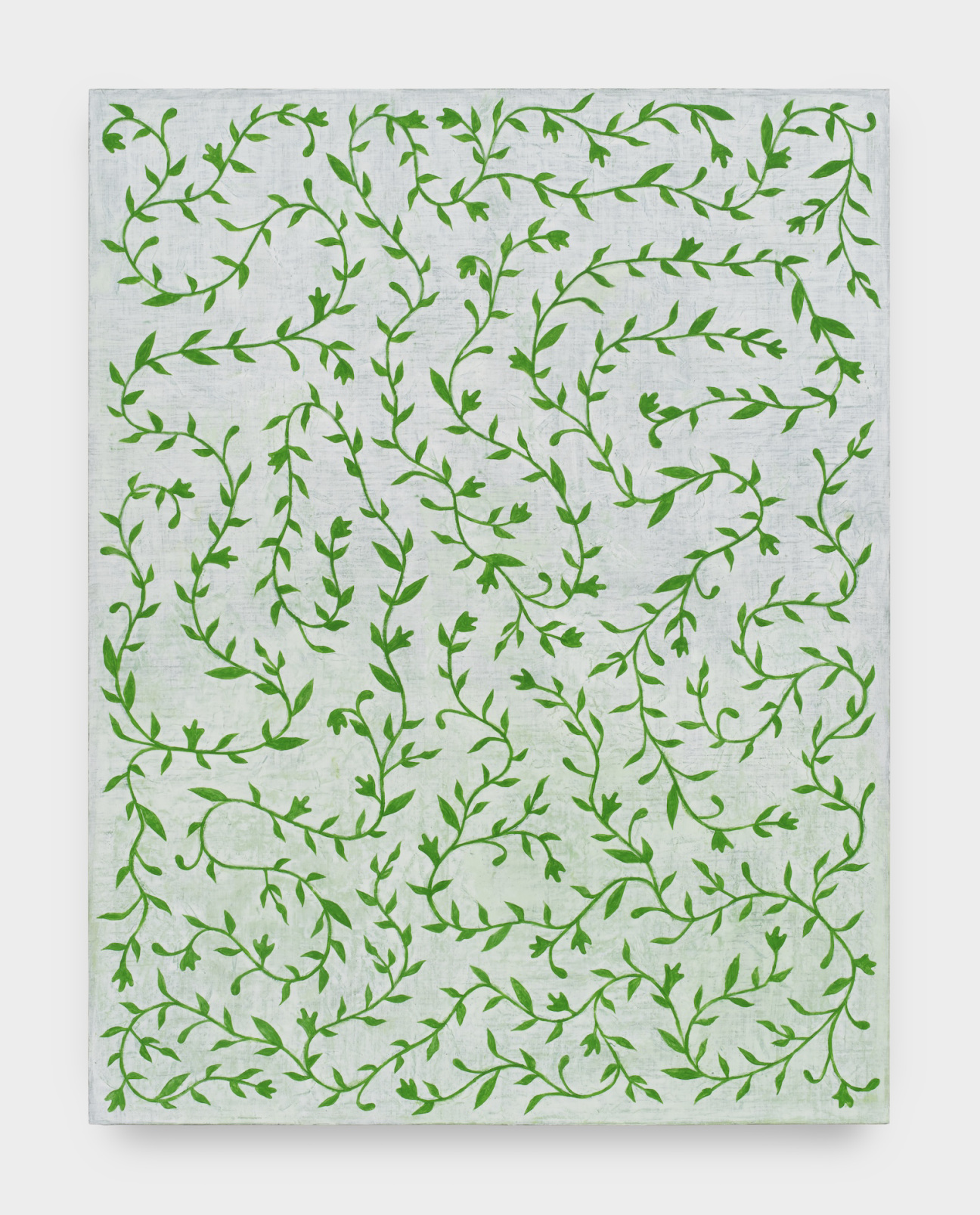

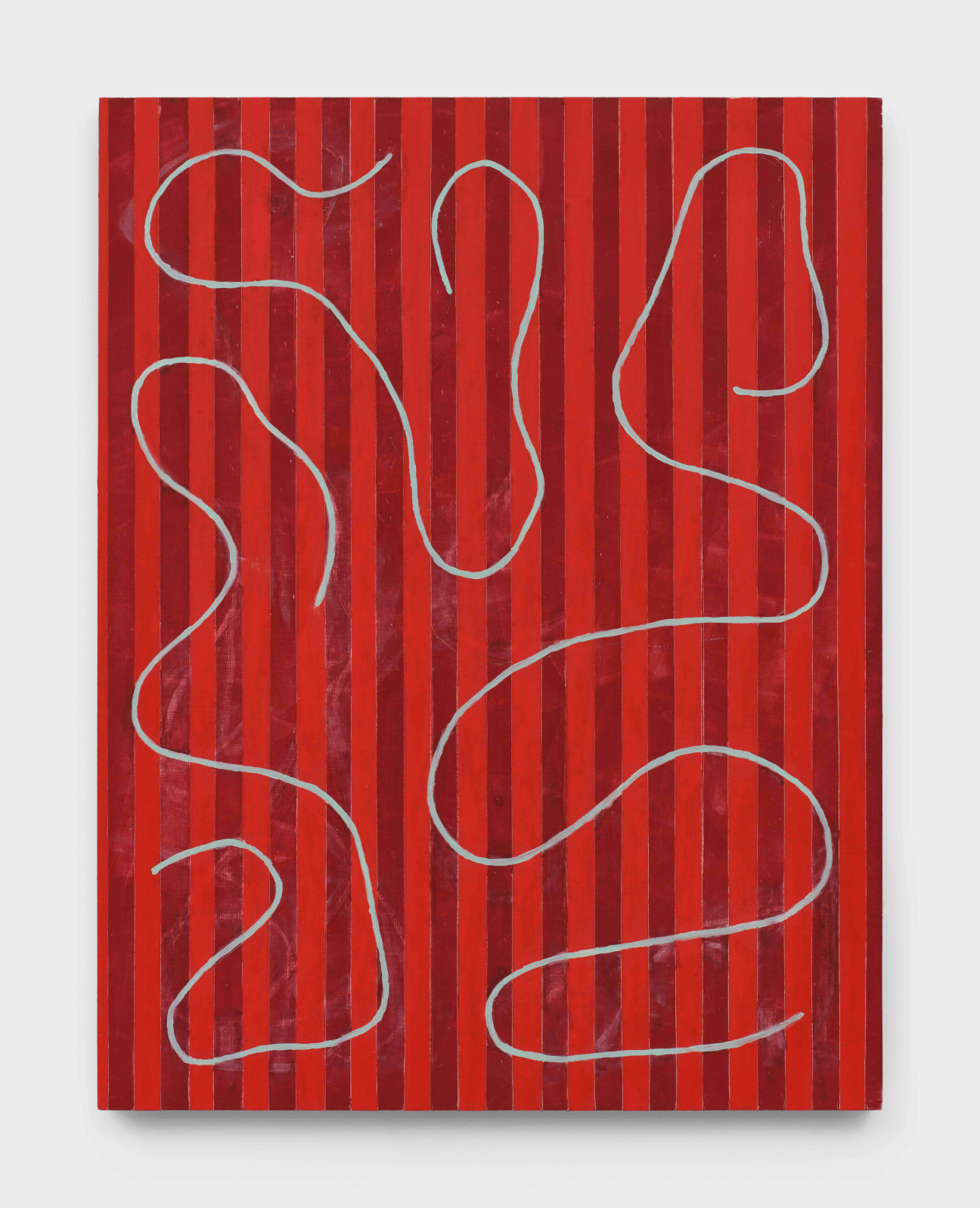

Wood: In your current paintings, I think it’s really exciting that you try out so many things, but they all carry a similar energy.

Sharp: Thanks. Some aspects of my work are consistent from painting to painting; one of them is pace and a change of pace. I think it comes from the different energies I bring to the studio from day to day. Sometimes, I’m patient and can take my time and sit with it. Other times, I need to do something quick. Sometimes, the work asks for it. I like that contrast within the work and embrace it with caution instead of employing it as a duty—not forcing it.

Wood: Something I find interesting about this show is, aesthetically, how singular Denzil’s works are, and how your paintings become a sounding board off of that. I’m not trying to force a comparison in the work, but I think the works relate through the idea of wanting to balance and push forward shape, color, and geometry.

Sharp: One connection could be how the painting is the thing. Containers and boundaries. Someone can always bring in references to other things when they see any painting, but with Denzil’s work, it’s undeniable that the thing on the wall is its own thing; it’s self-contained. This is also important to me because I think of the objectivity of a painting. I am very conscious of limiting my compositions to the confines of the support. I embrace the idea that my paintings are things on a wall as opposed to a window.

Wood: What I’m most excited about is people seeing your work, people seeing Denzil’s work, and people seeing the works together. It’s really important that Denzil has gotten eyes on his work at his own pace. It’s interesting because he was seemingly so against the art world. Not in a “fuck you to the art world” way, but more so that he refused to participate in the expectations of the art world.

Sharp: When you say he was anti-art world, maybe he felt like there was a lot of fluff out there and didn’t want to participate because he was such an academic. I remember him giving us these dense essays to read and then pounding the table and saying,“This is important! You’ve got to know this stuff!” He introduced Blinky Palermo once to a bit of laughter and then said, “Yeah, funny? Funny name, maybe—SERIOUS artist!”

Wood: I think Denzil cared enough that he wanted people to transcend their position. If you’re trying to get people to, in thought and in practice, push forward, you have to be aggressive with your thinking. Like him showing us Yve-Alain Bois’ “Painting as Model”— did any of us really understand it? [Both laugh] maybe it wasn’t Denzil’s actual words that had an impact on me, but the idea of what he was trying to convey. Always keep pushing yourself forward. Practice painting. And practice drawing, because if you’re good at drawing, then you’re good at painting. You know?

Sharp: There’s a rigor to it all and a specificity. What he was doing was open enough for you to absorb what you could, wanted, or needed and take your own path; use what made sense and continue your travels.

Wood: We were lucky to get his attention, because I needed that attention. I was impressionable and unformed, I was a lump of clay. I needed to be coached by somebody as rigorous about painting as Denzil. I really appreciated that. He had such a big impression on me, even though you wouldn’t necessarily see it in my work. UW was the perfect place for me to learn from somebody as serious as him, amongst others.

Sharp: There were so many perspectives.

Wood: He had this amazing multi-panel painting hanging in a great museum in Seattle. Yet, his main focus was teaching us that what really mattered was being in your studio and getting your shit together.

Sharp: Great perspective, important takeaway: do the work first.

in your life?

in your life?