William Leavitt and Raul Guerrero, “Time and Place” at Marc Selwyn Fine Art

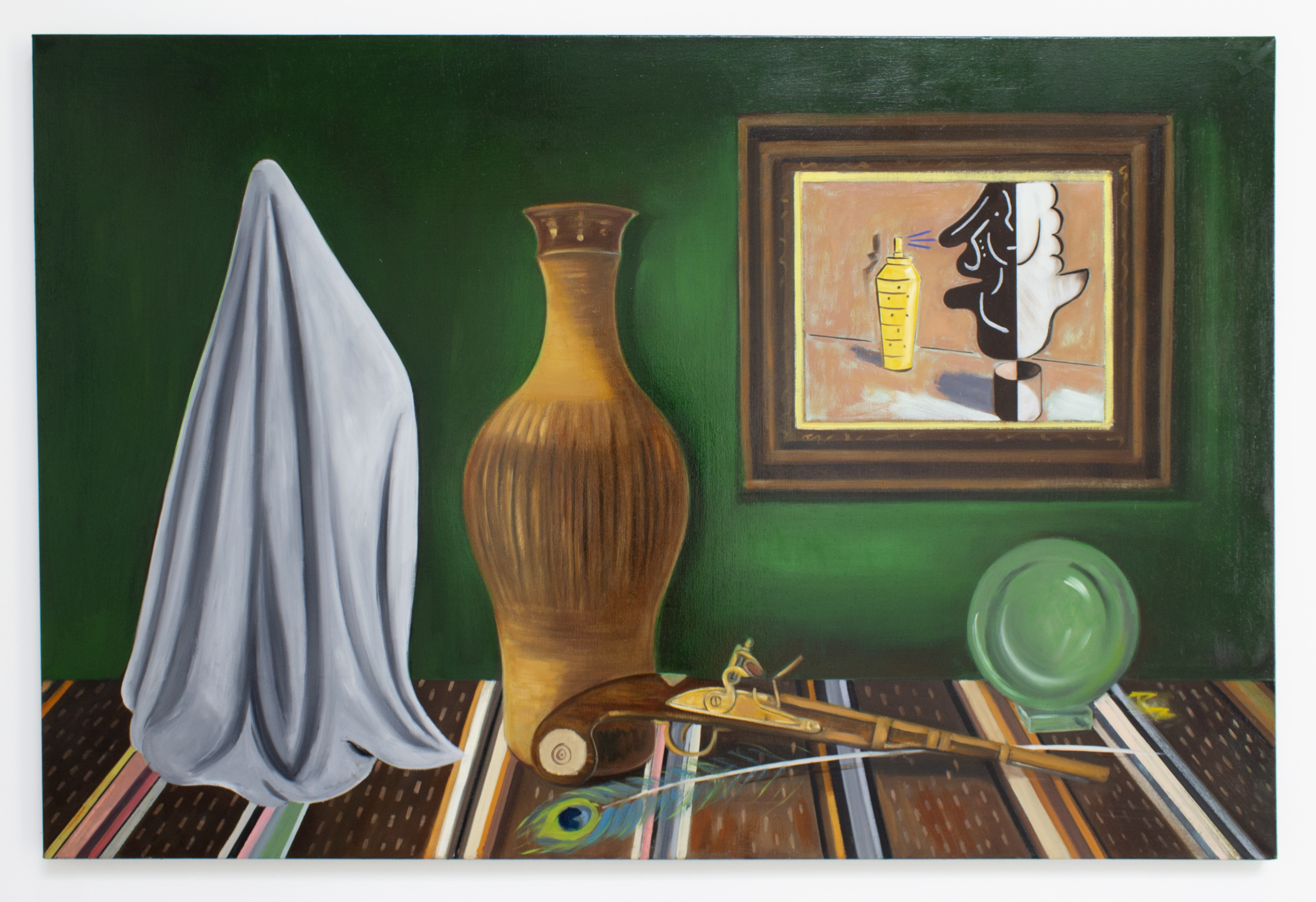

Raul Guerrero and William Leavitt are exemplars of a brand of art from the 1970s sometimes called California Conceptualism, a shaggy post-medium approach that drew on surrealism, popular culture and the Los Angeles dreamscape with a wry sense of humor. Curated by Leavitt, best known for his eerie tableaux of suburban Southern California domestic interiors, the exhibition offers a presentation of mostly recent paintings by these not-so-recent friends. Leavitt’s works, whether on paper or canvas, collage imagery of the Western landscape, built environment and interior details, rendered in a muted illustrational style. After working predominantly in sculpture, installation and photography since the early 1980s, Guerrero has devoted himself to painting. The selection of his works here comes, with one or two exceptions, from the past decade: still lifes, landscapes, a bar scene and film still. The cumulative effect is a historical phantasmagoria mixing indigenous American objects and modernist icons, Spanish Golden Age painting and Mexican Golden Age cinema, five centuries of narrative and counter-narrative that end at the bottom of glass in La Jolla.

Mark McKnight, “Hunger for the Absolute” at Park View / Paul Soto

Mark McKnight’s photographs—alternately of nature and men having sex in nature—reward in-person looking. There contain the simple pleasures furnished by meticulously printed photographs, especially when they’re big (as some of these are) and black-and-white (all of them)—depth of detail and rich materiality. But, of course, there’s nothing simple about pleasure. Amid the clouds and grasses and fistfuls of flesh, there are shadows so black that they only be called absence. In one photograph, we peer into the orifice of a dead tree, fallen but propped up on branches as if on all-fours: it’s a void of such depth that it wants to suck in everything around it. The sex, although it gets rough—there are chains and BDSM acts done to phalli—has a kind of quiet that is almost elegiac, as if, like nature, sex’s days were numbered. Start staying your goodbyes.

Clarence Holbrook Carter, “American Surrealist” at Various Small Fires

It is amazing how these figures continue to get dusted and polished: overlooked or altogether unknown twentieth-century figurative painters, preferably oneiric in mood or fantastical in subject matter. I’ll see your Gertrude Abercrombie and raise you a Clarence Holbrook Carter. But just because this sort of painting was long out of fashion and is now very much in fashion does not mean that it is merely a matter of fashion: this is a fascinating show, a collection of highlights from an artist of obsessive and hypnogogic vision, whose life nearly spanned the whole of the twentieth century. In The Lady of Shalott, the earliest work in the show, from 1927, Carter renders Tennyson’s famous poem, a favorite among the Pre-Raphaelites, as a graphic nocturne. Recurring throughout the show are ghostly egg-like forms, which over the decades he made float through landscapes, peek through windows and hover over tombs. The best work, though, is a series called Over and Above, in which various animals—a screaming baboon, a massive spider—peek over flat walls of color with an almost trompe l’oeil effect, a playful unleashing of the animal spirits confined within monochrome painting.

Pippa Garner, “The Bowels of the Mind” at Stars Gallery

I recommend waiting until dark to drop by this 24-hour kinetic window display. With hanging T-shirts bearing jokey slogans and a polymorphously perverse multicolored inflating-deflating contraption, Pippa Garner has imported a bit of the kitsch orgy of Hollywood Boulevard a block south to this ground-floor commercial space in a marvelously banal new condo building. It’s a gallery that, I swear, until last week was The Gallery @ but I now they tell me is called Stars. And Garner is a star. She used to go on with Johnny Carson and Merv Griffin, showing off satirical inventions and gag consumer goods. Her sense of humor—a little naughty, a little corny— seems more or less unchanged. There’s a shirt (that I wouldn’t mind owning) that says: “Art critic: ‘Where do you get your ideas from?’” The response: “Artist: ‘The sh#t just pops into my head.’” Voila: the bowels of the mind. On the floor, the inflatables gently throb.

Melvino Garretti, “Vino’s Carnival of Ceramic Curiosities, or the Circuitous Path to Calamity” at Parker Gallery

It seems Melvino Garretti kept busy during the past year: the funhouse of ceramics at Parker Gallery is all of a COVID-times vintage. There are woozy, candy-colored statuettes and miniature tableaux of clowns and carnival rides, and a suite of wall-mounted masks dressed up with strips of African textile. Though the man is drawn, clearly, to zany subjects, figures and forms (e.g. a guy standing atop a giant penis that wears a kind of sunburst cock ring), the particular delirium of the experience has everything to do with the ocular density of squealing color and pattern: Garretti has a distinctive approach to glaze, which he deploys in a rather painterly manner. He came to ceramics in the mid-1960s, when he was one of the original residents at Studio Watts—the workshop which served as a key hub in the Black Arts Movement in Los Angeles—and through which, in 1969, he participated in choreographer Anna Halprin’s epochal performance Ceremony of Us. Amid the fantasia of the present show, we get little outbursts of topicality: Lil Wayne’s pardon, a mask wearing a COVID mask and a memorial to the great John Outterbridge, who died in November, depicted at the end of end of his ride, on his back at the bottom of snaky slide.

in your life?

in your life?