In February 1969 in Boston, Emile de Antonio’s In the Year of the Pig—a cutting documentary condemnation of U.S. policy in Vietnam— received its official theatrical premiere. By then, de Antonio had cemented a reputation as a rabble-rouser of the mid-century American establishment. His earlier nonfiction features poked gaping holes in the straightforward narratives this country’s authority figures like to proffer about their deeds. Point of Order (1964), sculpted from nearly 200 hours of CBS kinescopes detailing the 1954 Army-McCarthy hearings, outlined the famously unhinged fear mongering of the Wisconsin senator—while refraining from presenting McCarthy’s across-the-aisle colleagues as unblemished interrogators. The film exposed the overall procedural buffoonery of a government body conducting an unfocused investigation for a national-television audience—as when McCarthy and Joseph N. Welch, the chief counsel for the Army and deliverer of the storied “Have you no sense of decency, sir?” inquiry, engage in a standoff over the meaning of the word “pixie.” Rush to Judgment (1967), which de Antonio completed in collaboration with the lawyer Mark Lane, tore apart the credibility of the Warren Commission’s assertion of a lone actor, Lee Harvey Oswald, in the 1963 Dallas assassination of John F. Kennedy. Pig elicited such intense passions over its jeremiad against America’s ignorant involvement in Southeast Asia that several attempted premieres were aborted owing to vandalism or threats of violence.

Yet for someone whose work caused such notable hysteria in its day, de Antonio stands presently as a somewhat sidelined figure in the 20th- century documentary canon. Occupying a status of “relative obscurity,” as Ed Halter termed it in a 2018 essay for 4Columns, de Antonio’s movies are difficult to access on the typical streaming outlets, and are certainly less frequently shown than those by contemporaries, like the direct-cinema practitioners Albert and David Maysles or the still-working institutional purveyor Frederick Wiseman. Robert Greene, the director of some of the most acclaimed documentaries of recent years (Actress, Kate Plays Christine, Bisbee ’17), recalls that, even as an employee at the legendary Kim’s Video & Music, the de Antonio offerings were slim pickings—some stray VHS tapes, including one of America Is Hard to See (1970), about Eugene McCarthy’s campaign for the 1968 Democratic nomination. “When he made those movies, he was in the conversation,” says Greene. “And then none of the stuff was available after that.” But efforts have been made in recent years to buck this trend. In April 2016, the Whitney Museum of American Art hosted a weekend of de Antonio screenings—an appropriate venue given the director’s manifold associations with the movers and shakers of the New York art world. “He was a sort of impresario, a raconteur, an incredibly erudite man,” offers the Whitney’s Donna De Salvo, who helped organize the three-day de Antonio event. “He had an extraordinary understanding of power, structure, and capitalism in general.” (Notably, when the new downtown Whitney debuted its first show, in 2015, it was with a de Antonio-esque title: “America Is Hard to See.”) Later in 2016, the Museum of Modern Art unveiled a digital restoration of Drunk aka Drink (1965), a movie de Antonio didn’t want released in his lifetime; directed by his close friend Andy Warhol, it displays de Antonio gulping down an entire quart of J&B scotch and lapsing into incoherence. Last year, Metrograph organized an exceptional de Antonio retrospective that included fresh 35mm prints of Point of Order and Pig.

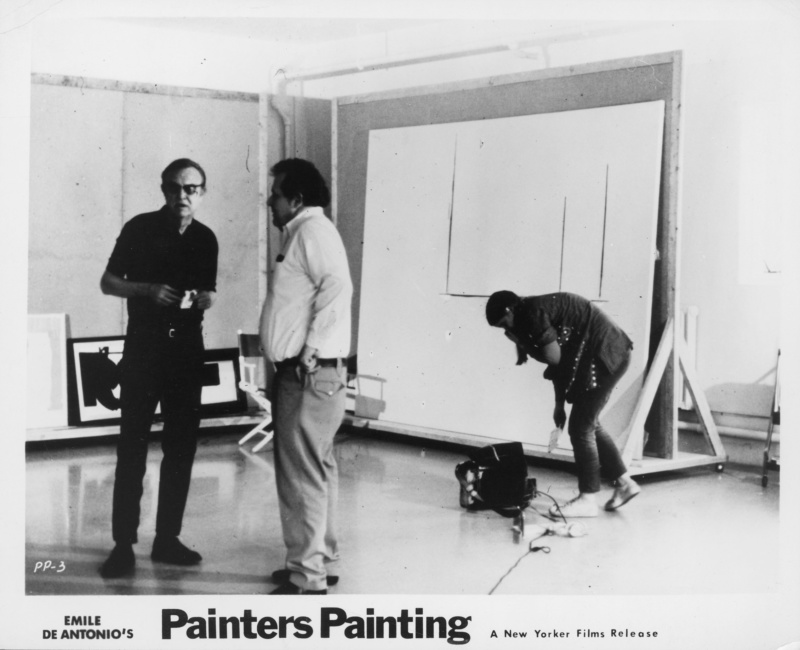

Cinda Firestone was a college student when she first saw Pig, which, like a lot of de Antonio’s left-of-center movies, found a fervent audience on university campuses across the country. She would go on to interview de Antonio during her tenure as a journalist at Liberation News Service, and then to collaborate with him, as an assistant editor, on de Antonio’s Painters Painting (1972). “His documentaries didn’t fall into a certain mold. They’re all very different. He opened things up for a lot of documentary filmmakers,” Firestone observes—including herself, who made her first movie, the pivotal prison documentary Attica (1974), after meeting him. “He was always very supportive of young filmmakers and young people in general. I thought that was a really nice quality about him,” Firestone adds, recalling a moment when de Antonio asked her, “‘Isn’t that what older people are for? To help younger people?’” For Greene, de Antonio’s legacy likewise looms large. “The biggest inspiration to me is, How can you make politics personal?” says Greene, who, as an undergraduate, was particularly moved by a set-up in Painters Painting in which the artist Robert Rauschenberg speaks to the camera while perched atop a ladder. “I think of that moment a lot. Why was that so singular? It taught me that every image needs to be an idea. That moment changed the way I think about art. Rauschenberg on top of that ladder—he doesn’t get there by accident. He and the filmmaker have agreed that this is the way to do this. That is the hallmark of what I want my cameras to do.”

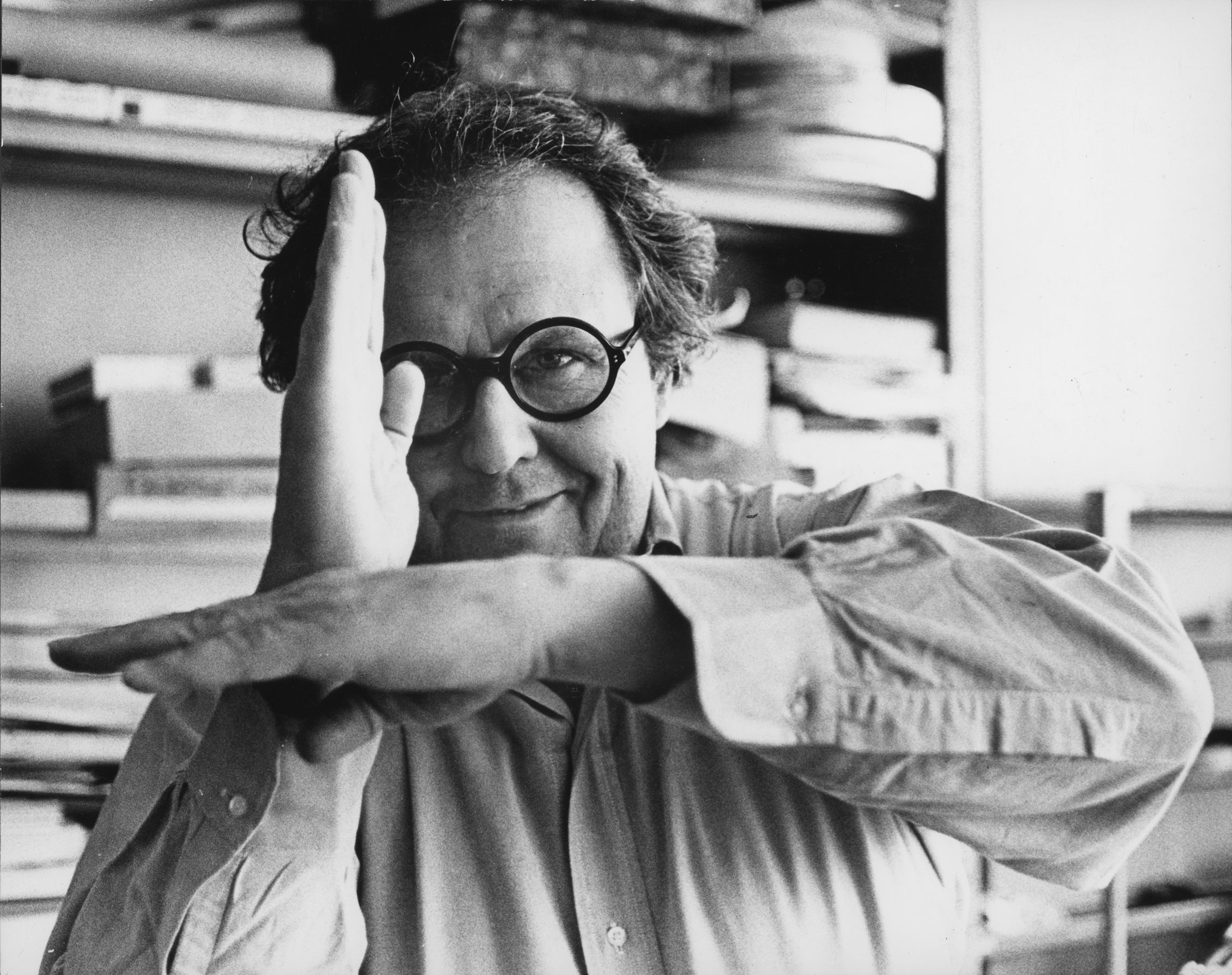

This lofty mission of formal experimentation and essayistic checks on the U.S. ruling class didn’t always seem a likely calling for de Antonio. A second-generation Italian-American born in Scranton, Pennsylvania, in 1919, de Antonio was raised in financial comfort and entered Harvard in 1936, the same year as JFK. He joined numerous leftist student societies, but his heavy-drinking habits caught up with him and he was eventually expelled, according to the telling in Randolph Lewis’ Emile de Antonio: Radical Filmmaker in Cold War America (2000), after “he set fire to an elevator … and then doused a university official with a fire hose.” He went on to odd jobs and a Second World War stint in the army. Later, he moved to New York to pursue graduate studies at Columbia University, where he held onto his disrespect for academic orthodoxy. Meanwhile, his gift for socializing remained undiminished. During the ’50s, he fell into fast friendships with now-canonical participants in the postwar New York art scene: Warhol, John Cage, Frank Stella. “He impressed people because he was so cocksure,” says art historian and critic Barbara Rose, who first crossed paths with de Antonio around that time. Even amid all these connections, de Antonio didn’t seriously catch the moviemaking bug until he saw Robert Frank and Alfred Leslie’s Jack Kerouac–narrated Pull My Daisy (1959), now considered an emblem of the Beat Generation and the New American Cinema movement that would consolidate in the early ’60s.

In Point of Order, de Antonio reached his conclusions solely through his sly, achronological arrangement of the CBS recordings. With Rush to Judgment and Pig, he began to administer original interviews, although he still relied greatly on chunks of footage sourced from elsewhere: network television, foreign-language documentaries, little-seen clips buried in archives around the world. This tendency points to another core function of his work: media criticism. De Antonio was distrustful of television and its ability to streamline complicated stories for the masses. Rush to Judgment, for its part, assails the Warren Commission but also discovers culpability in a shell-shocked media conglomerate that bought too easily into the party line about Oswald. Some of that movie’s most quietly terrifying moments occur when ordinary, Texan observers to the Dealey Plaza bloodshed explain where they initially heard the motorcade-directed bullets coming from—only for them to admit that subsequent media reports led them to disbelieve their own memories and concede that the shots originated at the Texas School Book Depository, where the Warren Commission claimed they did.

As the ’70s dawned, de Antonio turned to the business of the U.S. presidency. America Is Hard to See (1970) reverentially relates Eugene McCarthy’s campaign for the office from two years prior. Far more acrid, Millhouse: A White Comedy (1971) mounts a stinging indictment of sitting President Richard Nixon, functioning partly as a spiritual successor to Point of Order, in that de Antonio considers Nixon’s emergence as a Republican standard-bearer a byproduct of the hysteria for which McCarthy laid the groundwork.

De Antonio’s next movies clung more closely to the types of people the director considered his peers. Painters Painting provides a loving profile of many of the generationally influential artists with whom de Antonio fraternized and collaborated: Stella, Jasper Johns, Barnett Newman, Hans Hofmann. In the comparatively tense Underground (1976), which emits a spellbinding sense of danger, de Antonio, the cinematographer Haskell Wexler, and the editor Mary Lampson (all of whom share authorial credit) embed themselves within a cluster of members of the Weather Underground, the radical left-wing organization. Given that the movie’s subjects were then among the most wanted people in America, Wexler’s camera photographs them at obfuscating angles: through mirrors, behind their heads, draped in eerie silhouette. In between deeply considered political remarks, the young activists toss off darkly humoristic asides to the crew—“Join us on the floor,” “My right leg is asleep”—that underscore the physical discomfort of the production and the larger reality of living under the scrutiny of federal investigators.

J. Edgar Hoover, the longtime FBI head who directed the vindictive policing of such dissenters, supplies the connective tissue of Mr. Hoover and I (1989), de Antonio’s fascinatingly weird, digression-prone last movie. De Antonio, who died at 70 in December 1989, appears on-screen for much of Mr. Hoover and I, unfussily facing the camera head-on in blazer and purple turtleneck. De Antonio’s to-the-lens, sometimes-hyperbolic decrees encompass not just Hoover’s harmful career but also autobiographical recollections from the documentarian’s past. Interspersed among these addresses are tranquil scenes of household mundanities: John Cage preparing a loaf of bread as de Antonio looks on; de Antonio receiving a laugh-filled haircut from his sixth wife, Nancy. The movie demonstrates the ironic irreverence, political resolution and mountain-high personal contradictions that made de Antonio such a singular entity—a hobnobber among the elite who used his connections and charisma to finance gallantly confrontational reflections on the U.S. political apparatus. Decades on, his work persists in awakening the sentiment—as true today as it was during the ’60s and long before—that the journalist Penn Jones Jr. voices at the end of Rush to Judgment: “Something is wrong in the land.”

in your life?

in your life?