From Nari Ward’s mid-career survey taking over the Barnes Foundation this summer and the excitement surrounding the 12th Havana Biennial last year—and Galería Habana’s presence at the Armory Show this spring—to the official opening of the region’s first contemporary art museum in Jamaica, the buzz surrounding the Caribbean art world is definitely heating up. “It’s not that suddenly out of nowhere there are great artists from this region. It’s just now suddenly they are being noticed,” says Rachael Barrett, the mind behind the Kingston-based museum, _space, which has been operating pop-up programming since December, and officially opens to the public on June 25. “Personally, I am keen to see this exploration conducted in a serious and balanced way so it doesn’t run the risk of being fetishized or reduced to a fad or bubble.”

The Dominican-born curator Daniel Baez, who works for Gavin Brown’s Enterprise in New York, agrees. With the help of his Puerto Rican-born partner, Tony Rodriguez, Baez and some island-based friends are looking to launch MECA (short for MErcado CAribeño), a contemporary art fair in San Juan, next May. “This is something very needed in the art world right now,” says Baez. “A new player, a different point of reference, something fresh, innovative and challenging.” Such innovations have been popping up at international art fairs (and biennials) over the past few years with galleries like Panama City’s DiabloRosso, Puerto Rico’s Roberto Paradise, the Dominican Republic’s Lyle O. Reitzel and Havana’s El Apartamento. Christopher Rivera, cofounder of the hip new San Juan space Embajada, says, “One of the most important factors is the ambassador factor.” He cites Embajada’s ongoing “Cave” project with the Lower East Side gallery Ramiken Crucible as an example. “We still have a lot to accomplish as a vibrant art community, but when you have an obstruction like the failure of a colonial economy system, we all push ourselves to the limits.” Here, we look at six artists from Cuba, Puerto Rico and Panama who are capturing a growing audience across the globe.

Cristina Tufiño While playing on the cobblestone streets of Old San Juan, Puerto Rico, in the ’80s, Cristina Tufiño got an education on “cults,” from Hare Krishnas dancing in the streets to ships full of Scientologists and American tourists claiming to be with the Children of God. “I was exposed to a microcosm of outsiders, artists, exiles and people pursuing spiritual freedom, and that was such a big part of my childhood,” says Tufiño of these foundational experiences. “I focus my career in San Juan because I like working with the issues there.”

While the current economic crisis is headline news, Tufiño is more interested in the island’s more intimate and quotidian concerns. As a teenager, she and her friends roamed the abandoned buildings of the Santurce neighborhood, which experienced an exodus of 100,000 people during the Reagan era: “Poking around a lot of concrete and seeing how these beautiful modernist buildings were built really left an impression on me.” So did her grandfather, the folk artist hero Rafael Tufiño. As a child, she would study his posters when her mother sent her to his workshop as punishment.

Though Tufiño trained in photography, after a 2012 residency at the Skowhegan School of Painting & Sculpture, Tufiño became interested in sculptures made from everyday objects. “As commodities, high heels, suntan lotion and pineapples speak to me of an economy of leisure and also of its exhaustion,” says Tufiño. Her photographic compositions of stilettos carved out of sand (Otro piedra para olvidar, 2015) and an installation of rotting pineapples and detritus from a Walmart in Caguas (Sediment Salad, 2015) give a new meaning to post-studio practices and the use of social debris in our new Gilded Age. “It’s a way to catch the moment. These things— whether aromas or an actual object—serve as a metonym or an artifact for a way of life.”

Currently, Tufiño is working with concrete, clay and silk (upon which she’s printing 3-D modelings of perfume bottles contaminated with viruses and debris) to comment on materiality and the flatness of screen culture. She’s also making a video titled Fuerza Oculta, focusing on her great-grandmother’s home which has been unoccupied for a decade. It’s also a study of the mid-century furniture, family-made artwork, occult tomes, concrete walls, tropical plants and Spanish tile floors that define the space. “There’s definitely a mystery to that place. It feels very off because the space is stuck in time, and several people have come in, got very freaked out and say it still smells like ham,” admits Tufiño, who imagines the video will serve as a component for a larger installation in a NADA Miami booth this December or in her 2017 solo show with San Juan’s Galería Agustina Ferreyra. “I definitely want to translate that mood into the sculptures so I may work with ham because my aunt, who lives next door, comes in and feeds the spirits.”

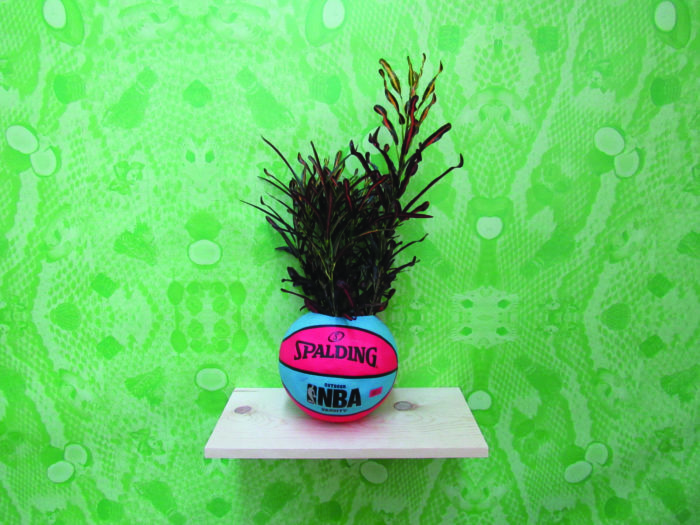

Radamés “Juni” Figueroa As a kid raised between the suburbs of Bayamón and the mountainous landscapes of Orocovis, Puerto Rico, Radamés “Juni” Figueroa played competitive basketball and learned to tend the cafetines owned by his grandparents. “There was no escaping it—I spent my days listening to music from the vellonera (jukebox) and looking at old drunks playing pool,” recalls Figueroa, whose work references an adolescence spent behind bars and under hoops, dreaming of music and folkloric landscapes.

Around 2007, he synthesized these interests into the Tropical Readymades—planted ferns inside of discarded, cut-out sports balls—which have become a hit at fairs from NADA to Zona Maco. Figueroa exhibited them at the latter last February inside a bright yellow, multi-tiered booth of his design for Mexico City’s Anonymous Gallery. “I associated basketball with city life and the fern to my life in the country,” says Figueroa, who also transformed his fascination with air conditioners—a Puerto Rican’s most vital appliance—into sculptures which recently went on display at ltd los angeles. “Whenever I had the opportunity, I would scratch them and make drawings on their back end. That was when I began doing graffiti and I ran into quite a bit of trouble.”

That troublemaking has paid off: Italian curator Jacopo Crivelli Visconti recently invited Figueroa to work on one of Oscar Niemeyer’s buildings for the São Paulo Biennial. He’s also developing a record label called Warevel Socio, planning collaborations with several Puerto Rican bands, working on a solo exhibition for Guatemala City’s Proyectos Ultravioleta, and curating an exhibit at Embajada of unseen work by the Puerto Rican artist Jesús “Bubu” Negrón.

Ariamna Contino Growing up the daughter of a San Alejandro Academy of Fine Arts professor and one of the founders of the Experimental Graphics Workshop of Havana surely influenced the trajectory of Ariamna Contino’s artistic career. Whether it was flipping through the Matisse monographs her mother used in her classes or accompanying her father in cutting and folding papers to make his engraving matrixes, the level of conceptual and technical precision in her increasingly provocative razor-cut works on paper has turned Contino into a hot topic beyond the chic Havana studio she shares with three other rising Cuban talents (Frank Mujica, Adrian Fernandez and her boyfriend and collaborator, Alex Hernández Dueñas).

Her fretwork incorporates white paper or cardboard that is bent and folded to separate each layer, forming multidimensional portraits, still-life and abstractions with “ghost images.” “What really led me to the work on paper was its poetic and symbolic nature. Paper is a raw material, the basis—if one may say so—of any representational process. It’s instinctive and noble; you may tear it, fold it, draw on it and even assemble it,” says Contino. “Being both fragile and sharp at the same time allows me to create a duality between delicate and dangerous. I am interested in developing metaphors that I complement with the possibilities given to me by the technique.”

Over the past two years, she and Dueñas have been teasing out the metaphors in statistical graphs and sociological maps sourced from the Internet and newspapers that chart trends in global drug trafficking, unemployment and war, as well as the ethics/ aesthetics divide. Her cut abstractions beneath his minimalist graphs painted on glass are encapsulated in a series of works called Aesthetic Militancy. “We have always defended this open work structure in which we indulge in assuming risks together when we believe we have a project that is worth it,” says Contino. Considering her work will be on view at Havana’s Wifredo Lam Center of Contemporary Art, the Ludwig Museum in Koblenz, Germany, Washington, D.C.’s Museum of the Americas, and Galería Habana (for a solo show) next year, it appears that those risks have been justified.

Jhafis Quintero Two years after the U.S. invasion of Panama, Jhafis Quintero broke out of jail where he had been sentenced to 60 months as a teenager for robbery. He fled to Costa Rica, robbed a bank with some friends and was then sentenced to 10 years in prison there. “My life at that time was just pure inertia, making random decisions because I liked the high doses of adrenaline,” says Quintero. In prison, he met a woman named Haru Wells who taught art as a method for rehabilitation in the third year of his sentence. “I went into the workshop just to avoid the repetition and routine, but eventually I discovered that both crime and art were like twin sisters,” says Quintero. “They had in common the same appetite for transgression. This experience became my laboratory. In such extreme circumstances the human being has no choice but to be human in the most radical way.”

After being paroled in 2005, he got a job and spent his nights and weekends turning his incarceration into the powerful series of photographs, In Dubia Tempora, which featured prison shanks set against ultra-white backdrops that evoked fine jewelry catalogues and Robert Mapplethorpe’s irises. The works were then turned into a book, debuted at DiabloRosso and now grace the library walls of Casco Viejo’s American Trade Hotel. Quintero followed these works with a handbook of drawings that teach new prisoners how to survive maximum security facilities (Máximas de seguridad, 2006), transfers of prison-style graffiti onto concrete panels (Cambalche), and his most recent series, Prosthesis, featuring plaster casts of hands holdings knives, strings to establish contact with neighboring inmates, and mirrors—the cellphones of prisons worldwide—that hung from the walls of Madrid’s Galería Sabrina Amrani last year. (Quintero staged a performance demonstrating the communication system with the public, whom he gave drawings to via strings during the 55th Venice Biennale.)

“In freedom, the basic instinct of any human being is self-preservation. In prison, this instinct is second. Atop the list is communication,” says Quintero, who is now based in Verona, Italy, but travels back to Panama and contends it will always be his spiritual (if not physical) home. “Wherever I am I feel Panamanian, but when I’m home I am known as an artist who was a criminal. The justice system doesn’t forgive, so I’m afraid if I ever went back to live there I’d still feel that weight on my shoulders. In Europe, I am simply known as an artist.”

Arlés Del Rio Known by locals as the “sofa of Havana,” the Malecón is a form of sculpture unlike any other in Cuba. But during the past two Havana Biennials, the iconic seawall has been dominated by the sculptural work of one artist: Arlés Del Rio.

For 2012’s Fly Away, he commented on the physical and political limitations of socialism by cutting the silhouette of a jetliner into an ominous chain link parcel overlooking the sea. Then, last year, for a piece titled Resaca, he created an accidental beach—frequented by thousands of locals during the course of the Biennial—by unloading dump trucks full of sand (and a handful of thatched umbrellas and chaise lounges) onto the boardwalk where the city’s famed sea baths once existed before the wall was built.

“Every year, hundreds of meters of sand transgress the Malecón through the undertow as if it wanted to reclaim the space lost on the Havana shoreline. The idea was to allude to the past of the area and what the future might be,” says Del Rio, 40, a self-taught artist who learned to make objects from his seamstress mother and the sculptors and painters in the Vedado apartment where he grew up (and still lives). His installation career first got off the ground in 1998 after he filled broken trucks from the Cayo Cruz dump with massive flies made of trash during an underground rave at a dilapidated sports center. “I was trying to get the spectator to reflect about the importance of rescuing forsaken, unhealthy places.” That sentiment still seems to be at the heart of his practice.

Last fall at New York’s Robert Miller Gallery, Del Rio restaged The Need for Other Airs—which debuted during the last Biennial inside the Cabaña fortress, where he attached 2,500 multicolored snorkels to a vaulted ceiling inside one of the fortification’s ancient cells. He is also preparing two installations for a project in Berlin next year, and working on a series of drawings made with hair collected from local barber shops, as well as a forthcoming collaboration in Brooklyn with José Parlá and JR. “As some friends told me recently, the street is the largest art gallery,” explains Del Rio. “I really identify with that. I don’t consider myself entirely a materialist or conceptualist. I’m a little bit of everything.”

Donna Conlon and Jonathan Harker When Donna Conlon’s husband was offered a job in Panama City with the Smithsonian in 1994, the former biology student uprooted her life in upstate New York and started making sculpture in the city center. “I wanted to have some academic context for it, but at that time there were no graduate programs here,” says Conlon, who traveled to Baltimore from 2000 to 2002 to get her MFA at the Maryland Institute College of Art. Upon returning to Panama, which had regained control of the Canal, she met the Ecuadorian-born artist Jonathan Harker.

“People were really starting to do interesting things,” says Conlon, who met Harker at a party and hit it off. “We had pretty immediate mutual respect for what each other was doing, and we were looking at some of the same things that were happening at that time in Panama City.” Harker had originally moved to Panama in 1986 to be closer to his father. Conlon had seen his short film El Plomero and he had seen her film Urban Phantoms, so when she invited him to a glass recycling center on the outskirts of the city (a location for some of her earlier photos), the two ended up turning it into the subject of their first collaborative video, Dry Season, which features tossed beer bottles crashing onto a mountain of green glass. The piece had a certain poetic and polemical quality to it and in the decade since that inaugural effort they’ve made many more seminal works.

From 2010’s Domino Effect (featuring a domino setup made from bricks that traces the historic boundaries of Casco Viejo to talk about the porousness of the walled city’s UNESCO World Heritage status) to 2015’s Under the Rug (a video showing junk being swept beneath a sod rug to address the nation’s collective memory loss), their pieces have appeared everywhere from DiabloRosso to the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. “At the center of each of these projects are objects—antique paving bricks from the city’s old quarter, plastic bottle caps, coins that were minted in an inflationary one-off by a corrupt Panamanian president—that represent a situation that we find ironic or offensive or somehow worth breaking open and delving into,” says Conlon. Adds Harker, “Most of our ideas tend to emerge from improvisations and games based on conversations about things that interest us in one way or another.” The two are now busy on a video about the beauty and chaos of spontaneous urban flooding in the tropics, and another that is intended to be, as Harker explains, “a dreamlike meta-narrative flux about existence as a continuous gamble between life and death.”