Some artists are alchemists—tinkering with our vision and transforming the ordinary. One such creator is Cai Guo-Qiang, who makes magic of his media. He turns gunpowder into dragons and ladders of light reaching into space; he makes wolves that rage across the sky and tigers arrested in mid-air by scores of arrows.

His studio in Downtown Manhattan sprawls behind a red door in a former school building. Inside, a quiet team of assistants works in one room, while new and old pieces of art are on show in the next: Colorful, recent experiments in gunpowder and pigment hang alongside older drawings of Chairman Mao, which allude to Cai’s childhood in Quanzhou, China, during the Cultural Revolution.

Millions of people around the world have seen Cai’s work—from the languid, smiling participants in the 2013 Parisian One Night Stand to the New Yorkers who gaped at a simulated car bomb tumbling through the rotunda of the Guggenheim Museum in 2008, to all those who watched the gobsmacking firework spectacle he designed for the opening of the 2008 Beijing Olympics.

Cai has spoken about the influence of the landscapes his father drew on matchboxes which, when he was a young boy, seemed to compress time and space. Now a lithe 58-year-old, Cai is still striving to bend the mortal coil.

There is a sense that he is trying to communicate beyond this world with explosion works such as the Project to Extend the Great Wall of China by 10,000 Meters or Sky Ladder, a climbing work of flaming light extending into space. References to meteorite craters and black holes consistently appear in his work, while his latest piece riffs on the idea of a white hole.

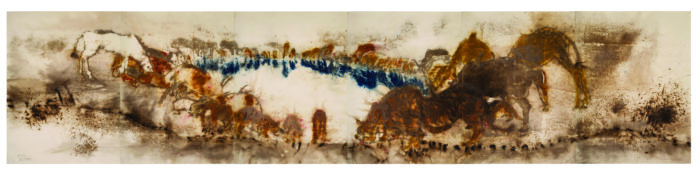

White Tone is a two-dimensional take on Heritage, a large installation that comprised 99 life-size replicas of animals—predator and prey—gathered around a water hole. Commissioned by the Queensland Gallery of Modern Art in 2013, Cai has reimagined it as a gunpowder drawing for the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain’s exhibition “Le Grand Orchestre des Animaux” (“The Great Animal Orchestra”), which runs from July to January 2017. The show is based on a book by American bioacoustics expert Bernie Krause, who investigates the aural landscapes of animals.

Cai wanted to “create the effect as if there’s a white hole that could absorb the animals,” and is “very interested in the cosmos.”

“We think of that soundless condition as a sheer darkness, but, for me the sheer whiteness could be an equivalent to that soundless condition,” he says. “I was really thinking about how to create a white hole. It’s easy to explode something black but it’s not easy to explode something white.”

“It is one of the most detailed gunpowder drawings Cai has made,” says curator Thomas Delamarre. “Even though Cai has worked with gunpowder for so many years, it’s still a very fragile process. There’s a very primitive energy in the results. “Maybe it’s due to the explosion—you can smell and see it in the paper afterwards.”

Cai notes that he and the Fondation Cartier have a long history together: It was “one of the few Western institutions” that worked with him in the early 1990s. Their partnership is “a very good example of when an artist is still young and starts a relationship with an institution and it develops. When it’s not just a one-time collaboration, then it can be a shared journey of growth.” He wanted to create an orchestra but also “to make chaos and mess up the orchestra—though, at the same time, I was afraid that I would really mess it up,” he says, laughing. “There is this intense oscillation between the two conditions, which generates a strangely interesting tension.” He strives for work that is not “too perfect. It’s important to have a sense of adventure and take some risks—which there always are with gunpowder.”

Alchemists searching for an immortality elixir discovered gunpowder—one of the so-called “four great inventions” of China—in the ninth century. “Gunpowder means fire medicine in Chinese,” says Cai. “It has a healing function—it can turn destruction into creation. Something I talk about a lot with the Fondation Cartier is this idea of using poison to conquer poison, turning fire against fire.

“The use of gunpowder is connected with the Cultural Revolution”, adds Cai, who remembers burning his father’s precious books at the time. The Cultural Revolution “relates to destruction and violence. We shouldn’t pretend that what happened in the past can be forgotten. Rather, we should just face it and create something out of it.

“Art for me is like a time space channel. It allows me to face all those disturbing matters,” he says. “While we face those problematic matters, we have this time space channel, which is art, for us to get away from reality, to communicate with eternity.”

Cai’s work intersects art, science, philosophy, memory and creativity. “I feel there is something fundamental in my culture which can resonate with people and that includes my belief in notions such as our all being unified before the Big Bang,” he says. “Various lives, objects and matters are unified; they have something in common. We share the same point of departure, a so-called hometown.” He uses his art for this purpose: “My English is not that good but I manage to communicate with different people across the world.

“As an artist, I tend to be lonely. But through art I am constantly having conversations with society,” he says. “Art for me is an interesting approach, a means of connecting. So, just by thinking of upcoming projects, I will feel excited.”

in your life?

in your life?