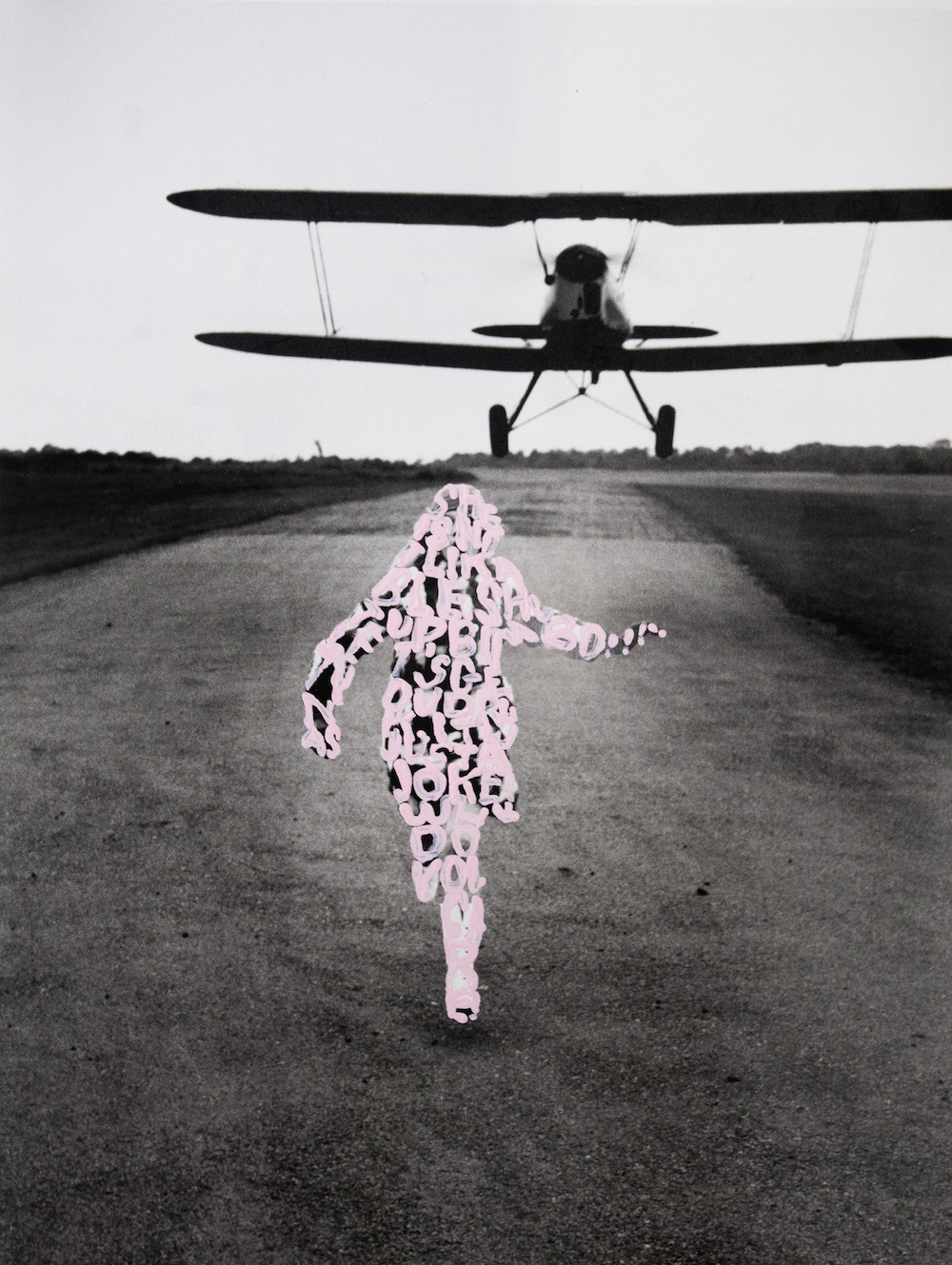

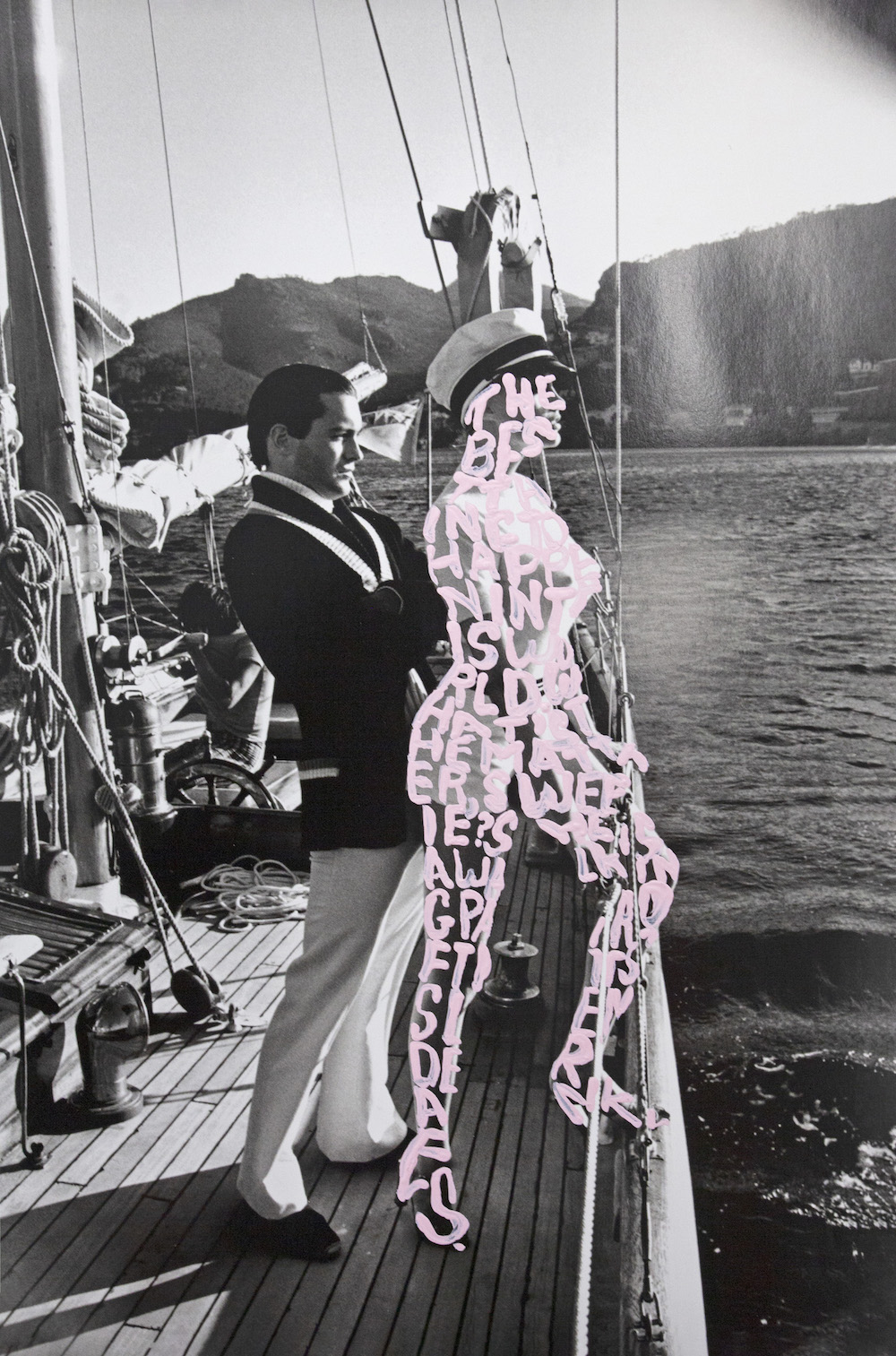

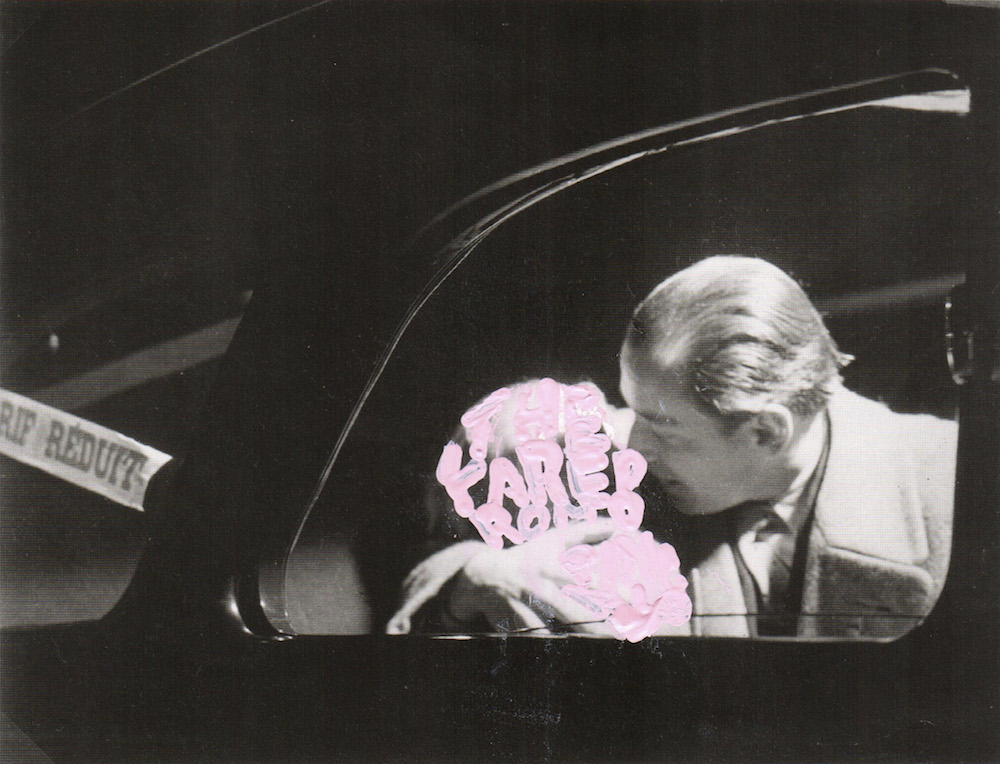

Artist Betty Tompkins is best known for her sexually explicit paintings of cropped closeups of sex and genitalia, a series called “Fuck Paintings” that she started in 1969. Shocking, censored and often rejected, Tompkins puts a provocative mirror in front of some of society’s most private, charged activities. In recent years, she has embarked on a project in which she takes canonical images of women, painted or captured by men, and writes over the figures with words associated with women, revealing deep, pervasive misogyny that has existed throughout art and throughout history. Tompkins’s work is the subject of two current exhibitions, one at Gavlak Gallery in Los Angeles and the other at MO.CO Montpellier Contemporain, her first international survey. We visited her studio in rural Pennsylvania to talk about her new “Women Words” pieces with text from the #MeToo movement, as well as her journey from being rejected and ignored to having her art, “Fuck Paintings” and all, welcomed with open arms by the very country that first censored her.

Annabel Keenan: Your show at Gavlak features “Women Words” with text from the #MeToo movement. Your earlier works seem to build up to this historic moment.

Betty Tompkins: The #MeToo movement is really the first time in my career that what I'm interested in as an artist and what's happening in the world come together. Everyday, I read the reports from all the lawyers—I swear these men have the same lawyer—and there are 20 more #MeToo things happening. Reading it shows the amount of misogyny there is. It goes even deeper with embedded misogyny, which is what I call it when attitudes that women are expressing are misogynistic.

I realized I've lived with this all my life. We all have. And that was really a shock. When I cover women with words, there’s nothing left of them except for the language that defines them, that they will grow into, and have hurled at them.

AK: Have you ever started something and said, “I'm not finishing this” and stopped?

BT: Very rarely in my entire life, no matter what I'm doing. I’m more or less the “stick with it even if it kills you” type of artist. There was a reason that I wanted to do it and I have to trust that I saw or imagined something that would carry me through.

Unfortunately, or maybe fortunately, I like to get in trouble with my pieces. I'm happiest when I'm flirting with disaster and doing things that interest me, not things that work. I’ve seen artists hit on something successful and do that same thing over and over again. It sounds incredibly boring to me.

AK: How did you figure out what art interests you?

BT: When I was first in New York when I was 24 and 25, I loved going to Sidney Janis Gallery. I would ask to see something specific, and his director would let me go to the back and pull out whatever I wanted. Eventually someone would check on me and find this young woman sitting surrounded by art with a big grin on her face. It was such a treat.

All the galleries were pretty much on the Upper East Side. You could see everything in one day. I didn’t distinguish between galleries, I went everywhere, but if after a while they don’t show anything interesting, why bother going? I would just be bored. I bore easily. And badly. One of my challenges in life is to not be bored. I say with whatever you’re doing, are you interested? No? Go do something else.

AK: How did you start making the “Fuck Paintings?”

BT: Not out of boredom. I had been working with spray guns as a graduate student. When I came to New York, I was living with my first husband in an apartment with two small rooms. He claimed the living room as his studio, which left me with the tiny bedroom. I finally said you can't spray in here, you'll die. So I went to Pearl Paint, bought an airbrush and taught myself how to use it.

My husband had a stash of porn. He was 12 years older than I was and he got it through a P.O. Box in Vancouver. It was illegal for that stuff to go through U.S. mail. I was looking at them after I just learned how to use the airbrush and I said, “You know, I think this is what you've been looking for.”

I wanted to make something charged, something I hadn’t seen before. I started cropping the images with my fingers and then with pieces of paper, getting rid of the feet, hands, legs, and heads, and I knew I’d found it.

AK: It's interesting you say that it's something that you hadn't seen, because you’re not creating a new image, you’re putting both a mirror and a magnifying glass on things that already exist.

BT: Sometimes when asked what I do, I say that I take something that exists in the real world, I do something to it, and then I hand it back. Maybe that makes it more shocking because I’m not making it up.

AK: How do you feel when there's resistance to your art?

BT: There are two things that I decided long ago. Don't explain your work. Don't defend your work. When somebody says something incredibly offensive to me, I don’t say a word. I'm fine. I gave myself a lot of freedom by doing this. My work is a loaded subject. Everyone who views it brings with them their entire sexual history, for good, or for bad, and I'm not responsible for that.

AK: Do you think the pushback has to do with the fact that you're a woman?

BT: Do I think so? Yes. Can I prove it? Not exactly. When I first started the “Fuck Paintings,” I went to galleries and said, “I'm working on this series of paintings. When I have enough (which I figured was 10) can I bring them in?” More than half of them responded, “You're too young, come back in 10 years when you’ve found your voice.” To them I said, “I've had a few voices in my lifetime, and when you have it, there's no doubt.” The answer, including from women dealers, was a universal, “No. Don't come back. We have no market for women artists. And we don't intend to develop one.”

AK: How did that feel?

BT: When I look back at it, I should have been crushed. It’s a terrible thing to hear when you’re 25 or 26, but I found it incredibly liberating. Here was the entire art world saying, “We're never showing your art.” I felt relieved. I could do whatever I want, whenever I want. Nobody's going to be criticizing this, because nobody's going to see it!

AK: So their rejection had the opposite effect?

BT: Definitely. It’s the same when I’m censored. When my work was first censored in Paris in 1973, I started a group of censor drawings. My attitude was, I can censor myself better than the French government. I’ve been censored so many times. I was censored on Instagram, censored in Japan. Each time, I censored the pieces they had censored. You want to censor me? Here’s your censorship.

AK: Now you’ve come full circle with your first international survey at MO.CO. Was the French censorship on your mind when planning this show?

BT: Oh, yes. It was on everyone’s mind. The show includes a large censor painting I made of one of the original French censored works. I realized at some point that I’d been making censor drawings, but I hadn’t made paintings. I had a canvas the same size as the censored “Fuck Painting” and a photograph of my source material. I grided it out and wrote “censored” in red paint all over the naughty bits. Now there it is in France after all.

Craving more culture? Sign up to receive the Cultured newsletter, a biweekly guide to what’s new and what’s next in art, architecture, design and more.