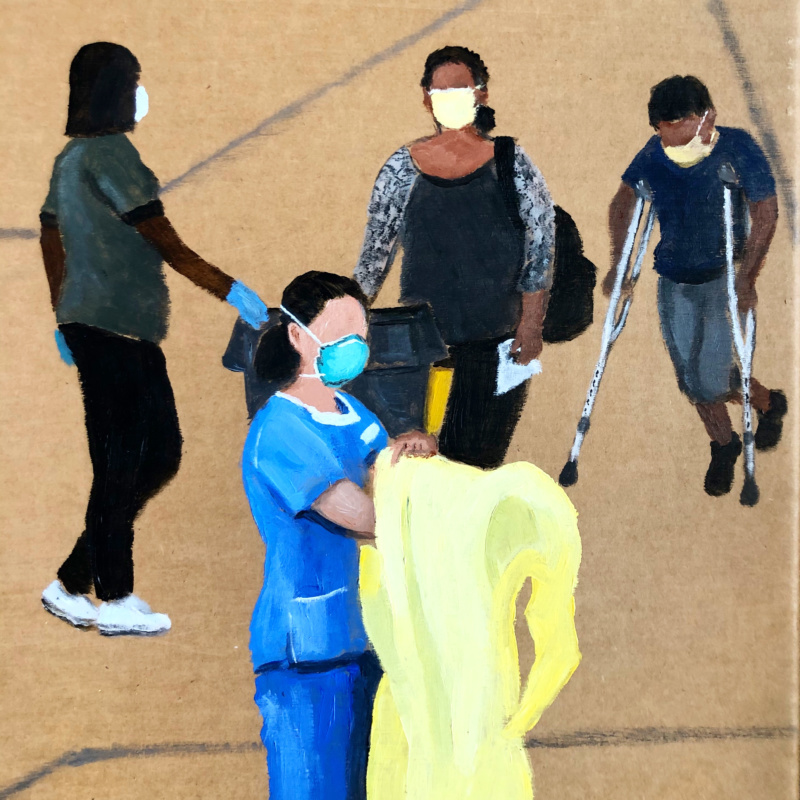

Ramiro Gomez, Jr. paints the people absent from home decor shoots and the modernist houses so valued by luxury advertisers, restoring the army of laborers—pool hands, uniformed maids, gardeners—who make such lush scenes of the “American Dream” possible in the first place. Famous for his subversion of Hockney’s 1967 painting A Bigger Splash, Gomez’s 2013 version—No Splash—reimagines a faceless man cleaning the Pop Art pool and a woman sweeping the patio in the backdrop. Initially, Gomez’s inspiration for his subject matter was sparked by his years as a Los Angeles nanny. During the children’s naps, he would look at architecture and design features in Architectural Digest, struck by the similarity to his own surroundings. From this, grew his celebrated magazine series, as much a diary of his lived experience as a record of the domestic workers erased from the visual and social landscape they are indispensable to creating. As the weeks of social distancing grind on, Gomez’s Instagram account has increasingly become an outlet for his practice, not to mention a daily destination among art insiders. I caught up with Gomez by phone in his West Hollywood home to learn more about how he’s been coping with work and life in the last few months.

During the pandemic, I’m struck by how quickly nannies and housekeepers became entirely expendable and families just stop paying them. I recall similar stories during the LA fires too. It’s interesting when I think back to my early days as a nanny. For the first few months that I worked with the family, there was a housekeeper who would come every Thursday. I bonded with her; I came to understand her family history in Mexico. It was an open format house, so I would be sitting in the living room with the twins, while she was cleaning the kitchen or other rooms. But one Thursday stands out vividly. She just didn’t show, and I remember asking myself, “Where’s Delia? Why isn’t she here today?” I just assumed maybe she was sick or something. But the next Thursday, somebody new came and I was forced to interact with that person like it was nothing out of the ordinary. There was never really an explanation for what happened to Delia. I know she had been with the family for a while, and then suddenly she wasn’t.

The reality and emotion you’re describing is what your P.P.O.W booth at The Art Show conveyed so deftly. That was the last time we spoke and it feels like a lifetime ago. There’s an irony right now that the very art institutions that are buying and collecting my work are also laying off their employees. That’s a strange feeling for me as an artist. Board members are making these cost cutting decisions to save curators at the Whitney, or the Hammer, or LA MOCA. They’re paying them through the shutdown, but then laying off the education coordinators and the people who aren’t “indispensable” to them right now. What about the janitorial staff at MOCA? Where are they in this situation? They aren’t unionized because they’re subcontracted. I relate it to my time as a domestic worker: people give so much of their bodies for nothing in the end.

Do you consider yourself a quintessentially Californian artist, akin to David Hockney or Ed Ruscha? In the end, I think of myself more in Andy Warhol terminology, as a mirror. My work is Pop Art. I’m reflecting what I’m seeing. If I’m in a house that looks like the one from Hockney’s A Bigger Splash, it’s clear to me that the pool cleaners and the housekeepers weren’t in David’s painting, so it’s even more important for me to express that. I’m consciously choosing when—and when not to—employ the California-esque landscape. Sure, Hockney, Ruscha and other artists were seen as influencing what that California view is. But they were in concert with filmmakers, landscape photographers and lifestyle editors who showcased this gorgeous view of the West Coast. Magazines that present beautiful homes—so casually, with a summit backdrop—build up that idea. By no means do I highlight the romance of it all, because I consider the undercutting layer. But it’s also not just California; my practice is universal. My structure and my strategy keep growing, constantly emerging with new ways of saying the same thing.

What was it like for you when, coming off the success of The Art Show, within a week or two the whole world shut down? I had already said to myself after P.P.O.W that I would give myself a necessary break period to recover. Rest for me is super important. I tell myself, “Okay, your body needs physical rest, not just mental rest.” The first few days were very hard, full of anxiety and no awareness of what was really going to happen. All these things were shutting down, but I was still in my “recovery period.” Normally when I’m home to recover, I go to my favorite cafe around the corner, Joey’s, or enjoy a night out with friends at a gay bar called The Abbey. The social component is an important part, along with the physical and mental rest.

Your Instagram doesn’t feel like you took much of a rest. It seems like you’ve been creating and engaging viewers more than ever during isolation? In the line of work that I do, this is precisely the moment that I have to keep pressing forward. As Nina Simone said, ‘It’s an artist’s duty to reflect the time.” When I start going into that quote, I think about all the artists who have had previous versions of struggles and created beautiful art out of it. So there is this expectation of artists, right? But it’s also personal for me. I love Pablo Picasso’s Guernica. I think about how he created a self-imposed isolation and then reacted to everything through newspaper accounts. I’m not saying I’m going to create Guernica right now. But, I am saying there’s a version of me that is aware, and then there’s another part of me that’s dealing with gender issue struggles and past traumas. The shows that I’ve been doing have started expressing those. For the first few weeks in isolation, I didn’t create physical objects. I was showcasing selfies of myself in lipstick and make-up on my social media, expressing something that I have been doing, but hadn’t been public about for fear of the reaction.

Do you tie that social media aspect of your art back to your thoughts on Andy Warhol? I was always shy about putting myself up front because I thought it would take away from the messaging of my art. I’ve always painted people that should be the focus but weren’t before. But then I realized in my last shows, I need to showcase my identity more. That only complicates the narrative that I’m presenting. I am a queer child of Mexican immigrants, and I shouldn’t leave that out for fear of reaction.

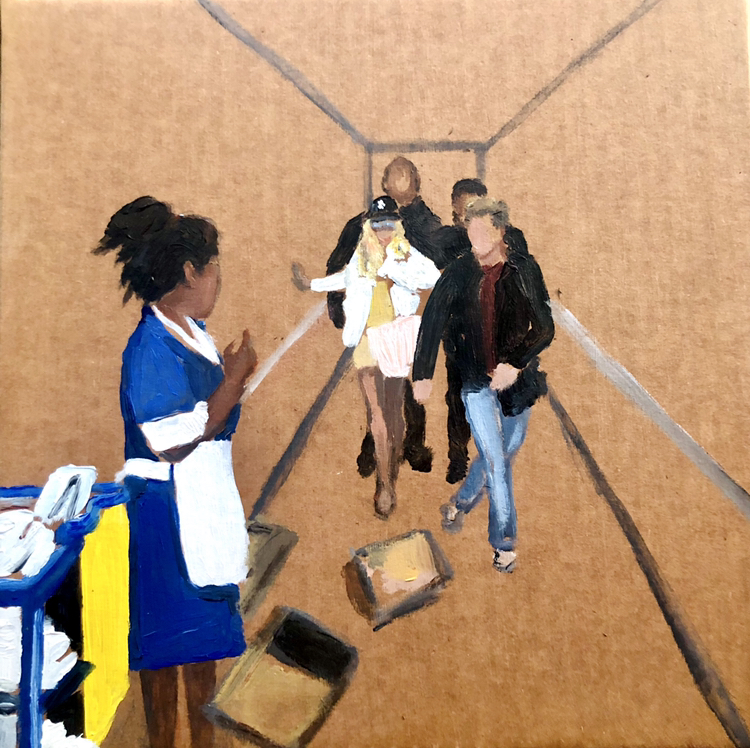

Can you tell me more about the new Britney Spears painting you posted on Instagram? Britney is gallivanting down a hall with her entourage, but the composition focuses on the hotel housekeeper. I’ve been kind of obsessed with the image. First, it’s key to know that music is super important in my process. During the lockdown, I started doing those social media challenges with friends that are floating around, and one of them was the 30 day song challenge. It asks you every day to share a song that, let’s say, reminds you of someone you’d rather forget or a song with a number in the title. And every day is different, so it forces me to recollect. One specific prompt asked for your favorite cover of a song. My answer was the song by Sondre Lerche—“Everytime”—which is a cover of Britney’s version. I love the original song too. Britney was one of my queens and there’s this moment in the “Everytime” video that struck me. The video takes place in Vegas; Britney is walking with Stephen Dorff through a hallway—they’re a couple and they’re fighting. Then, out of nowhere, Stephen Dorff’s character kicks a bunch of cardboard boxes towards a housekeeper, who’s like “what the hell?” It was so strange to look at the video. I said to myself, “I’m going to go to make a painting based on that scene and post it on Instagram, along with the song.” But I made my painting about the housekeeper. Britney and Stephen are devoid of their own features. I didn’t want them to be the focus, even though they are part of it. I think when you share work on social media, there is a kind of pressure, but it’s different than when you are presenting art for a collector at an art fair. The paintings I’m posting are for myself—and for an audience that is dealing with all these uncertainties too. Art is a respite. So I don’t question it. I just say, “Hey, let me share this work online right now.”

in your life?

in your life?