Step into Kelly Sinnapah Mary’s world, where memory and mythology entwine like ancestral threads. In "The Book of Violette," now on view at James Cohan in New York, the Guadeloupe-born artist conjures a dreamscape of matrilineal storytelling, Caribbean surrealism, and quiet defiance. Each brushstroke pulses with family history, honoring her grandmother’s legacy while grappling with the lingering ghosts of colonization and indentured labor. Here, transformation reigns—female figures morph, identities unravel and reweave, and the past refuses to stay buried.

With just a few weeks left to experience the show, CULTURED caught up with Kelly for an intimate conversation, where she reveals how everyday rituals—from her grandmother’s garden to the quiet power of Caribbean women—can literally reshape worlds.

CULTURED: "The Book of Violette" transports us into the world of fable, folklore, and history. In every story there is a lesson: What does Violette teach us?

Kelly Sinnapah Mary: My grandmother was an extraordinary woman I admired enormously, even if I wasn't very close to her. I saw her every day when I was a child, as my parents lived next door. Violette [Sinnapah Mary's grandmother] had this special bond with the Earth, as if she could speak to it, and she also had the ability to never give up despite difficult situations. She was the central core of the family, and her memory lives on in our minds and in the earth that absorbed her every step. "The Book of Violette" does not aim to represent Violette literally but is a starting point for weaving stories around the preservation of knowledge between generations.

CULTURED: What stories did you read as a child, and how have they shaped the narratives in your work?

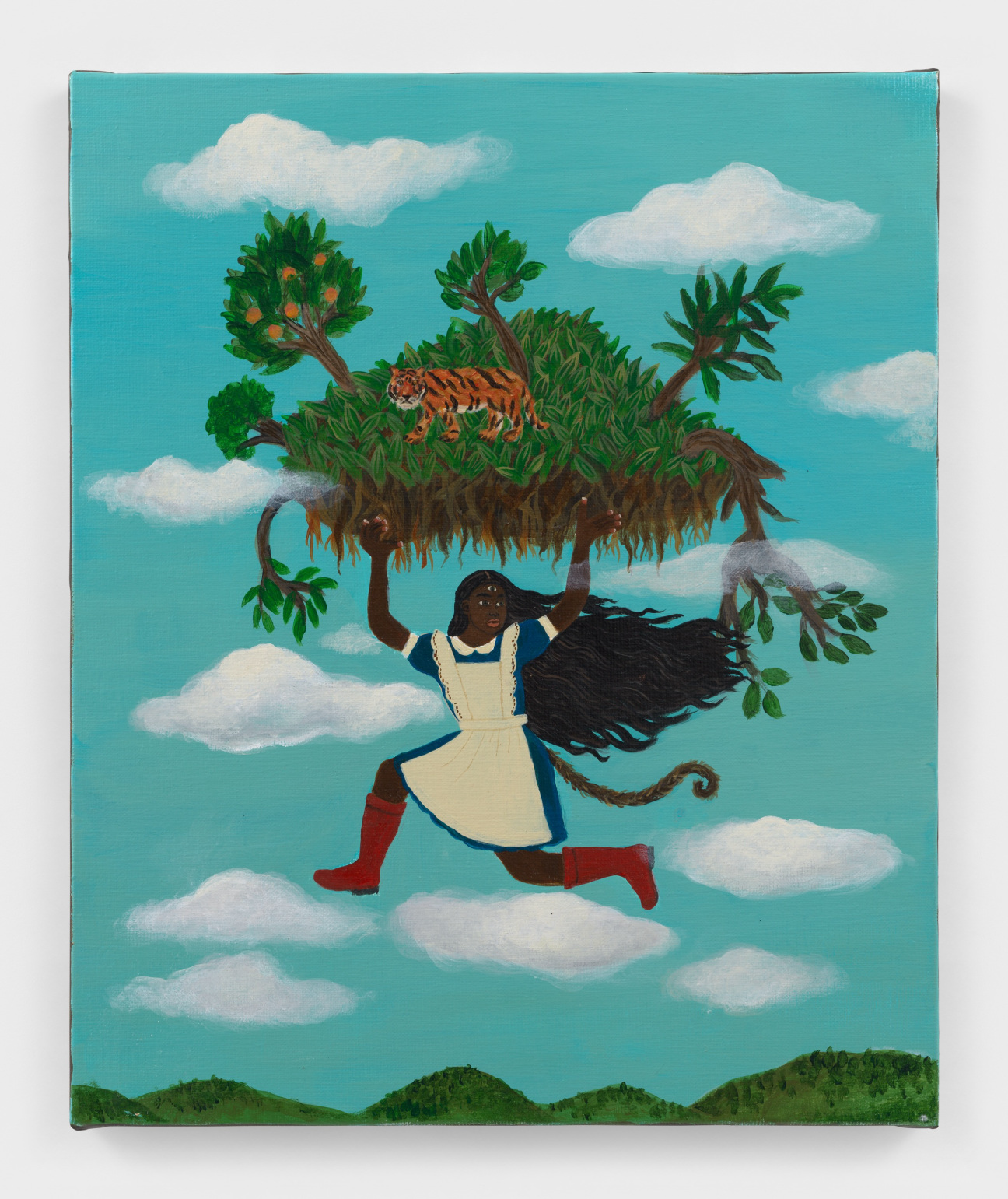

Sinnapah Mary: Many fairy tales and fables shaped my childhood, from Little Red Riding Hood and Cinderella to Little Thumb, Jack and the Beanstalk, and Alice in Wonderland. When I was little, my father used to read me Bible stories like David and Goliath, and Delilah and Samson. Looking back, I would have liked, like other Caribbean children, to be able to identify with characters who looked like me and recognize landscapes that resembled those in which I lived. Synthesizing all these formational references in my work led me to criticize and question them. If I'd been surrounded by other types of storytelling from an early age, what would it have changed for me in terms of my identity and my work?

CULTURED: How do you navigate the process of creation when blending mythology, memory, ancestry, and reality? Which do you channel first?

Sinnapah Mary: When I paint, I am channeling both my family mythology––the stories that have been told to me, the memories I have––and broader histories and cosmologies to imagine a new world. All this is rooted in me––in my body––so it's only natural that it should be transcribed in my work. I don't seek to control, but rather to create landscapes where mythologies, memories, ancestry, and reality can become one.

CULTURED: How does ritual in your daily life, like tending to your garden or living in Guadeloupe, influence your creative process?

Sinnapah Mary: I do not yet have a garden where I grow medicinal plants as my grandmother did or as my mother does––I am in the learning phase of their know-how, but I work at it and I do keep chickens. What mainly influences my work is the place where I am anchored. I mean that living, breathing, eating, sleeping, loving, reading in Guadeloupe rather than elsewhere directly influences my creative process.

CULTURED: How does Violette reflect your connection to your grandmother and to the larger cultural narratives of the Caribbean diaspora?

Sinnapah Mary: My grandmother is an icon for me in that she symbolizes transmission of knowledge, of memory, and cultural inheritance—but more than that, she was a guiding force of our family. In Guadeloupe, we speak of “poto mitan” to describe our Creole grandmothers, which means middle post, as we understand these matriarchs to be the pillar of the house and of society. The poto mitan also relates to spiritual concepts like axis mundi and the world tree. It always seemed to me that my grandmother practiced magic and its rituals. The multiplicity and change of form that I associate with religious magic seems so appropriate to me to envision the world handed down by my grandmother.

CULTURED: You’ve mentioned drawing inspiration from Caribbean intellectuals such as Suzanne Césaire, Maryse Condé, and Édouard Glissant. How did their writings initially speak to you, and how do they continue to shape the themes you explore in your art?

Sinnapah Mary: These three authors have occupied my mind for some time. Maryse Condé’s main characters are often strong women, like Tituba, who reminds me of the women of my family. Édouard Glissant's writings are so richly topical. Tremblement, a refusal of all categories of fixed and imperial thought. Building oneself in your relationship with others without losing the self is also a powerful lesson today in such a fragmented society. I find a lot of hope in Glissant's literature, in his incitement to create reciprocal bonds of exchange. In Suzanne Césaire's writing, she talks about reinventing the world through surrealism, calling for a revolutionary freedom of words and forms that is rooted in a uniquely Caribbean context. In my own work, the references are layered. I draw upon stories and iconographies from many realms and many cultures—from Caribbean literature to Hindu cosmology to French fables—to create as large a field of expressive possibilities as I can.

CULTURED: You’ve described your work as a visual notebook. How does this idea of a "notebook" guide your approach to art?

Sinnapah Mary: The idea of the visual notebook is reflective of my process. Every project begins with research—the first stage of each of my projects consists of gathering testimonies, iconographies, and histories of Indian indentured workers. For the past decade, my evolving understanding of my identity has been at the center of my work. I am a descendant of indentured Indian workers who were brought over to replace enslaved labor following the abolition of slavery in the French colonies of the Caribbean. This is a part of the story of our region that still exists in the shadows. It’s a part of me that I did not know much about growing up—my work has become a way to assemble the pieces of the puzzle that is my story.

CULTURED: Your work pushes back against the idea of humans being at the center of the world, a facet of imperialism. What role do humans play in your art? What about animals?

Sinnapah Mary: We live in the Anthropocene Age, a geological era that is characterized by humanity’s dominance on Earth, which has wrought a period of planetary disorder, from climate change to pollution to extinction. In my work, I push back against this harmful framework and instead build worlds that prioritize interrelationships and ties of kinship and care between humans, animals, and plant life. Insistence on the interdependence of living beings becomes a strategy of resistance and a way to restore balance and harmony.

CULTURED: Many of your paintings feature Violette with plant life tattooed onto her skin. Is this Violette in her human form or something else entirely?

Sinnapah Mary: There is always both a continuity of narrative, like chapters in a book, and an evolution at the heart of my work. Since 2020, my paintings have featured a character that I named Sanbras, a young girl in a schoolgirl's outfit who has the power to transform at will into an animal, plant, deity, or some hybrid creature. She is driven to create an eco-community with the protection of ancestral knowledge at the center. In this new series, Sanbras embodies my grandmother, Violette, her skin layered with pieces of personal history or plants that take the look of poultices that relieve the traumas of this history.

CULTURED: Your work reflects the idea that land holds memory, connecting the past to the present. How does this idea shape your exploration of contested histories and the lived experience of the diaspora?

Sinnapah Mary: The earth and landscapes of the Caribbean are imbued with the memories of our ancestors and are there to testify to our stories. I am fortunate to own land in Guadaloupe, land that I inherited from my parents, who inherited it from their own. Being a landowner––a steward of this land for the next generation––reminds us that our ancestors arrived in the Caribbean with nothing and had to make a place in this society that also became their own after much struggle. Having this small piece of land as their descendant is a treasure to pass on to our own descendants, along with their teachings and histories.