Laura Owens

Matthew Marks Gallery | 522 & 526 West 22nd Street

Through April 19, 2025

Early in her career, the Los Angeles painter Laura Owens placed the brushstroke in scare quotes and never looked back. I’m thinking of a small, untitled canvas from 1995 in which an enlarged daub—a cartoony version of a slightly drippy mark made by a flat brush loaded with gesso—hangs in black space. It looks like it could have been cut out: painting’s fundamental gesture recast as a gash. But the silhouette isn't empty; it’s been filled in with horizontal bands of thinned-out acrylic color. Brown on top, pink on bottom, a bright stripe of vanilla in the middle, it's a Neapolitan “brushstroke”—a new shape for ice cream.

For three decades, the artist has put her medium through the paces with her nose-thumbing post-post-modernist feminist formalism, a resolutely intellectual as well as humorous project of synthesizing alleged opposites—deskilled and reskilled aesthetics, the handmade and the digital, Greenbergian precepts and illusionistic space (for example). But all the while, dessert has never left the table. Beauty, inseparable from the social baggage of taste, is always present and always presented self-consciously, free from the delusion that it’s something greater or more complicated than what someone (such as the artist herself) likes.

She likes—or loves—wallpaper it would seem from her eponymous exhibition on view now at Matthew Marks Gallery. In her enchanting, enveloping, no-holds-barred return to New York after a long absence (she has not had a solo show here since her mid-career survey at the Whitney Museum eight years ago), foliate, floral, treillage, trompe l’oeil, and other patterns blanket, overlap, and seem to come alive on the walls. Painstakingly, elaborately crafted surfaces, painted and screenprinted (sometimes many times) by hand, extend the space of painting. Theoretically, they expand it infinitely, given the flexible dimensions of their repeating patterns. In another sense, the wallpaper—mostly Arts and Crafts, Art Nouveau, and Art Deco-inspired—pointedly shrinks the space of painting, making it coterminous with the domestic, traditionally feminine or feminized, sphere of décor.

Past an altered and mechanized vintage desk at the front, in the first warehouse-scale room of the gallery’s larger 22nd Street address, a group of commanding vertical paintings, each more than 10-feet tall, are installed on walls, exquisitely hand-decorated in muted, coordinating tones of what I think of as an early 20th-century boudoir palette. A base color of dusty rose or warm taupe is picked up by outlines and accents in the room’s dominant botanical print: milky, delft blue to seafoam green fronds join larger, white leaves against a ground of pale yellow. Oil, pastel, charcoal, and silkscreened Flashe on linen are listed as the materials for four of the five untitled abstractions (all dated 2025) hanging here. Owens works wonders with her ingredients: As is characteristic of her work, trickily layered elements speak in a profusion of tongues, this time evoking—with their passages of blown-up half-tone dots, hand-drawn Greek meander, and sweeping scribbles—both Cubist collages and the draped, SweeTarts-hued, abstract-floral print of a 1980s blouse. Occasionally, her hallmark stucco-y impasto smears appear, perversely pretty, like scatological/buttercream Easter eggs, color-matched or camouflaged to blend in and add dimension to their painted and patterned environs.

At the top margin of the room, a realistically rendered, floating tangle of pastel power cables becomes a chaotic frieze of ornamental S-curves and coils. The sinuous, unspooling mass catches up assorted treats in its dreamy flux—a pink-iced doughnut with sprinkles, a strawberry wafer cookie, and frozen fare, including a Choco Taco, a Creamsicle, and an ice cream sandwich (yes, Neapolitan), can all be spotted. It’s a particularly impressive marathon of quodlibet trompe l’oeil in a show that is clamorous with related forms of illusion (faux stone finishes and shallow quadratura among them), leaving a carefully executed shadow of its elements on the wall “behind” it.

The intoxicating tricks of this theatrical, larger-than-life interior prepare visitors to step “outside;” a pair of hidden doors (hinged sections of wall) swing open to reveal, in the next room, a fantastically verdant, semi-abstract indoor-outdoor courtyard garden of some kind. Here, the richness of clashing prints recalls the “femmage” works of Miriam Schapiro (and the Pattern and Decoration movement more generally), as well as the staggered or moveable elements of a puppet theater or stage set. The pale flowers of leafy primrose plants (I think) poke through an endless lattice; coral, fuchsia, and violet blooms appear in clusters on a variety of (printed) woven rattan surfaces; William Morris-y designs assert themselves as voice of reason; a bottom border depicting a golden grate recalls the gridwork of the Wiener Werkstätte; Monet-inspired, lily pad-like, sponge paint-ish cloud shapes drift by.

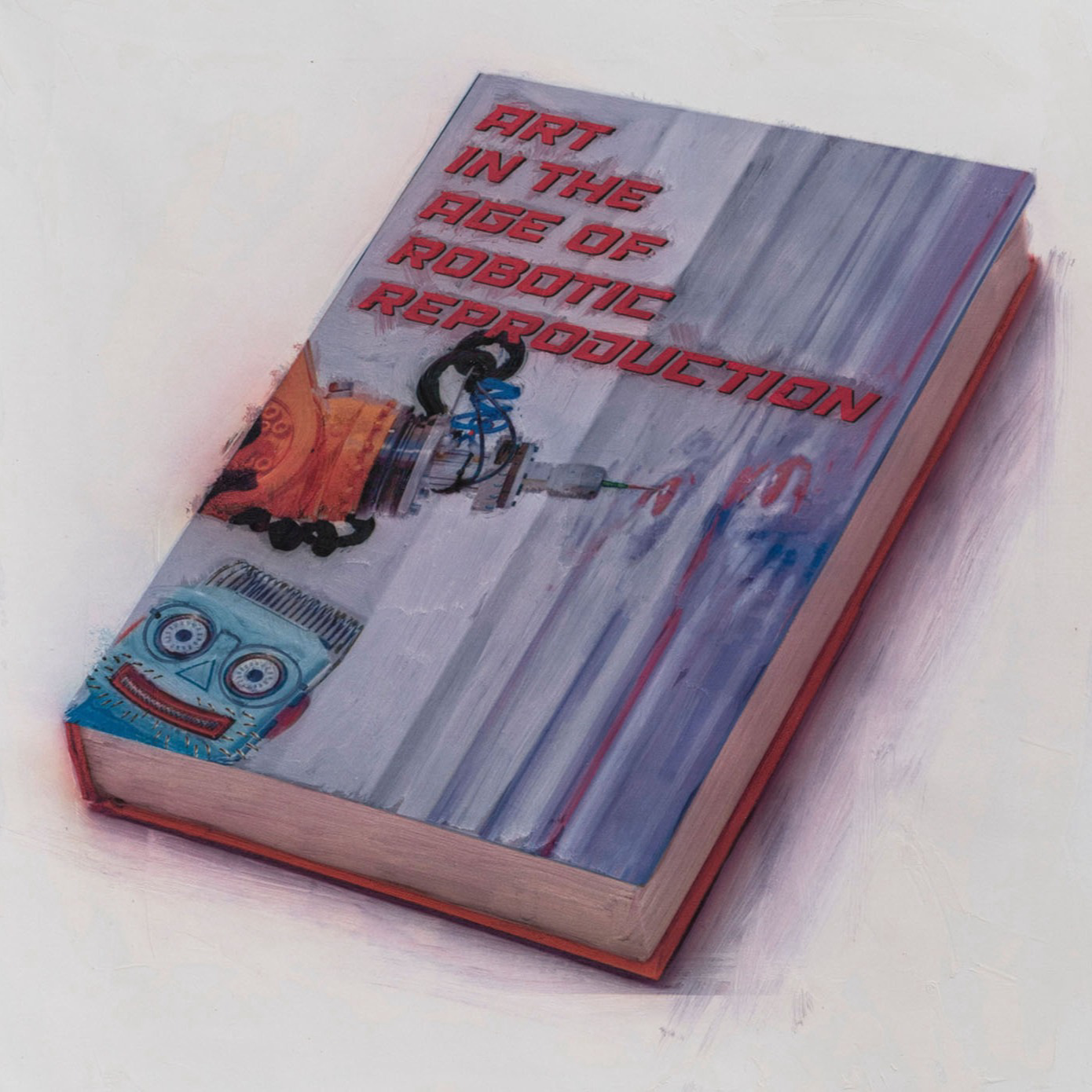

The checklist informs us that this rapturous Gesamtkunswerk was achieved with, among other things, sand, flocking, egg tempera, and clay-coated paper on aluminum panels. Next door, at the back of the gallery, past a group of tricked-out jewelry box or desktop organizers filled with books (handmade by the artist), Owens stages a more abstract rainbow-sherbet, twilight-grotto version of this. Constructed with the same materials, it is smaller and maybe even more heart-stopping for its more intimate offer of reprieve from this world. And the crafty box-sculptures, more intimate still, easy to breeze by on the way in, are, perhaps—with their patterns, textures, and compartments—offered as miniaturized, portable access points to such beauty: They struck me as more poignant on my way out.

There is one more room (back at the first space), its entrance located in the corner of room 2, closet-sized and painted a dark color. Visitors (a few at a time) can enter to view a video projected high on the wall, almost at the ceiling. With its 80-minute runtime, I assume you’re not meant to stand and gaze upward through the whole thing while people stand in line behind you. I caught a scene of two crows at a picnic table, conversing (via voiceover) about the existence of sexism avant la lettre in ancient Athenian society—a fascinating topic that seems to reflect obliquely on the artist’s overarching interests here.

For her 2021 exhibition-intervention at the Fondation Vincent van Gogh Arles (in a series of gestures kindred in spirit to Sophie Calle’s 2023 radical reconfiguration of the works of the Musée National Picasso Paris), Owens created an in-situ, multi-wall wallpaper “painting” on which she installed seven Van Gogh canvases. A recontextualization of the works in visual terms, the project also threw the artist’s ever-compounding myth—his intractable epochal vice grip on Western notions of genius—into relief. (“More people have seen an immersive Van Gogh experience in 2021 than saw Taylor Swift’s Reputation tour in 2018,” Owens mused in an interview.) The patterns serving as the Dutchman’s bold, immersive backdrop she derived from the work of the little-known designer Winifred How, whose 1916–1918 student portfolio Owens discovered at a book fair, and from another found portfolio by an unidentified French artist whom she presumed to be a woman as well.

In viewing wallpaper as a path to the past, in service of a feminist inquiry into Modernist history, related points converge. No doubt, a century or so ago, painterly ideas and passions were channeled into the applied arts as a result of women’s constrained professional and artistic horizons (and particularly into textile design, if the Wiener Werkstätte’s interwar roster is any indication). But such practices were an explicit interest of early 20th-century avant-garde women painters too, with Marie Laurencin’s wallpaper and decorative contributions to the Maison Cubiste of Paris Salon d’Automne of 1912; Florine Stettheimer’s legendary interiors and stage sets; and Sonia Delaunay’s fabrics, costumes, fashions, and books being notable examples. The newish inclusion of these figures in the canon as more than footnotes is not a question of plucking anyone from obscurity so much as critically reevaluating these activities as artforms in their own right—and as contiguous with the field of painting. (Delaunay was understood perhaps not so much as a footnote, but rather as a very accomplished wife.)

In Owens’s work there is an implicit critique of painting as décor, but, more compelling now is its obsessive celebration of décor as painting. Her tour de force of craft, excess, and flamboyance cues—for me—longing: I’d like to live here. But the show also digs into the aggressive, territorial, unreasonable potentials of decoration, dramatizing the expressions of taste and preference that might be wielded against the historical confines of the home, the walls themselves becoming a delirious, delicious means of escape.