“I think the tree is an element of regeneration which in itself is a concept of time. The oak is especially so because it is a slowly growing tree… It has always been a form of sculpture, a symbol for this planet ever since the Druids.”

— Joseph Beuys

On the morning of Jan. 8, I planned to see the Joseph Beuys exhibition at the Broad, but instead, I woke to the news that the Eaton fire had destroyed my home, art studio, and everything around it. I sat in a hotel with my wife and infant daughter, and stared in disbelief at the images of our community in ruins.

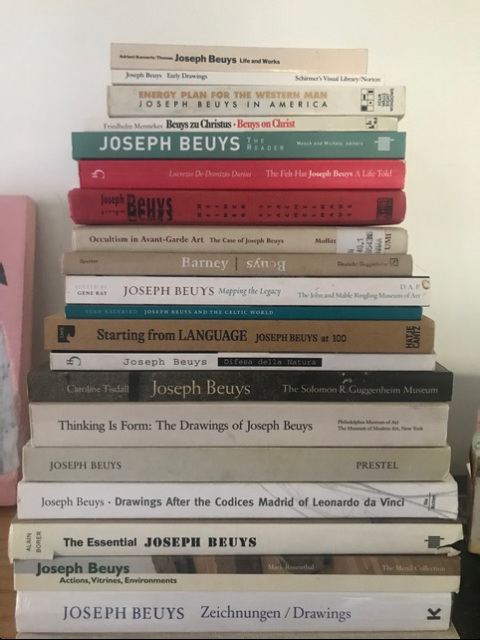

Along with my other possessions, gone is my library, which included a collection of Beuys books gathered over 20 years: monographs, biographies, volumes of interviews, and criticism. These are the only objects I’ve ever really collected. Now, only one survives: a book titled What Is Money?, which discusses Beuys’s idea of art replacing money. I brought it with me for what I thought would be some casual reading on an evening-long evacuation.

The Broad show’s title, “In Defense of Nature,” references the artist’s long-running social and ecological campaign of the same name, which included the planting of hundreds of endangered trees in the Italian countryside. I learned about Beuys’s environmental interventions from a now-burnt book of mine by the same title, written by Lucrezia de Domizio Durini, in which she chronicles a trip the artist took to the Seychelles in his 60s. There, he studied the landscape and, in a performance on Christmas Eve in 1980, planted two trees.

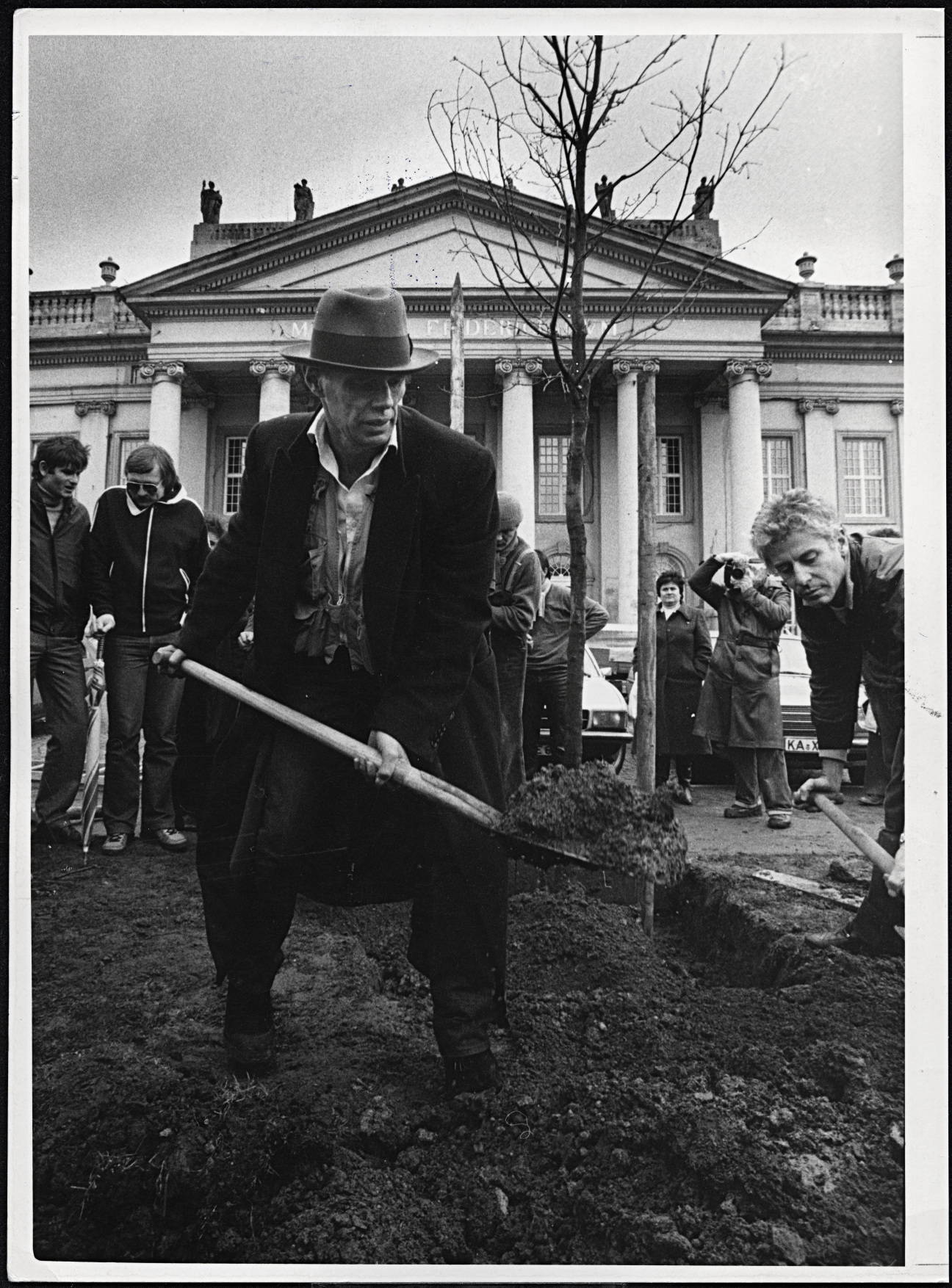

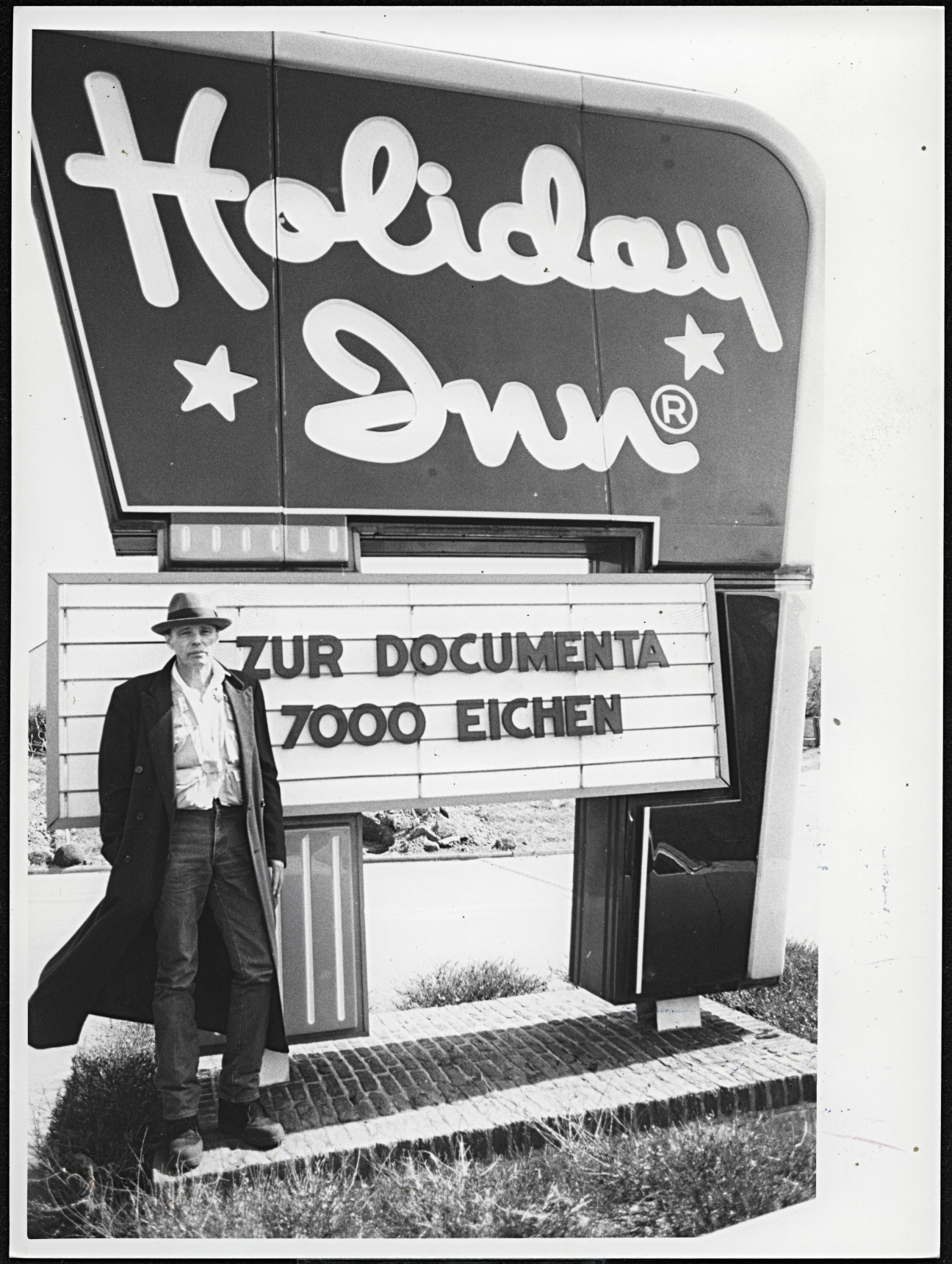

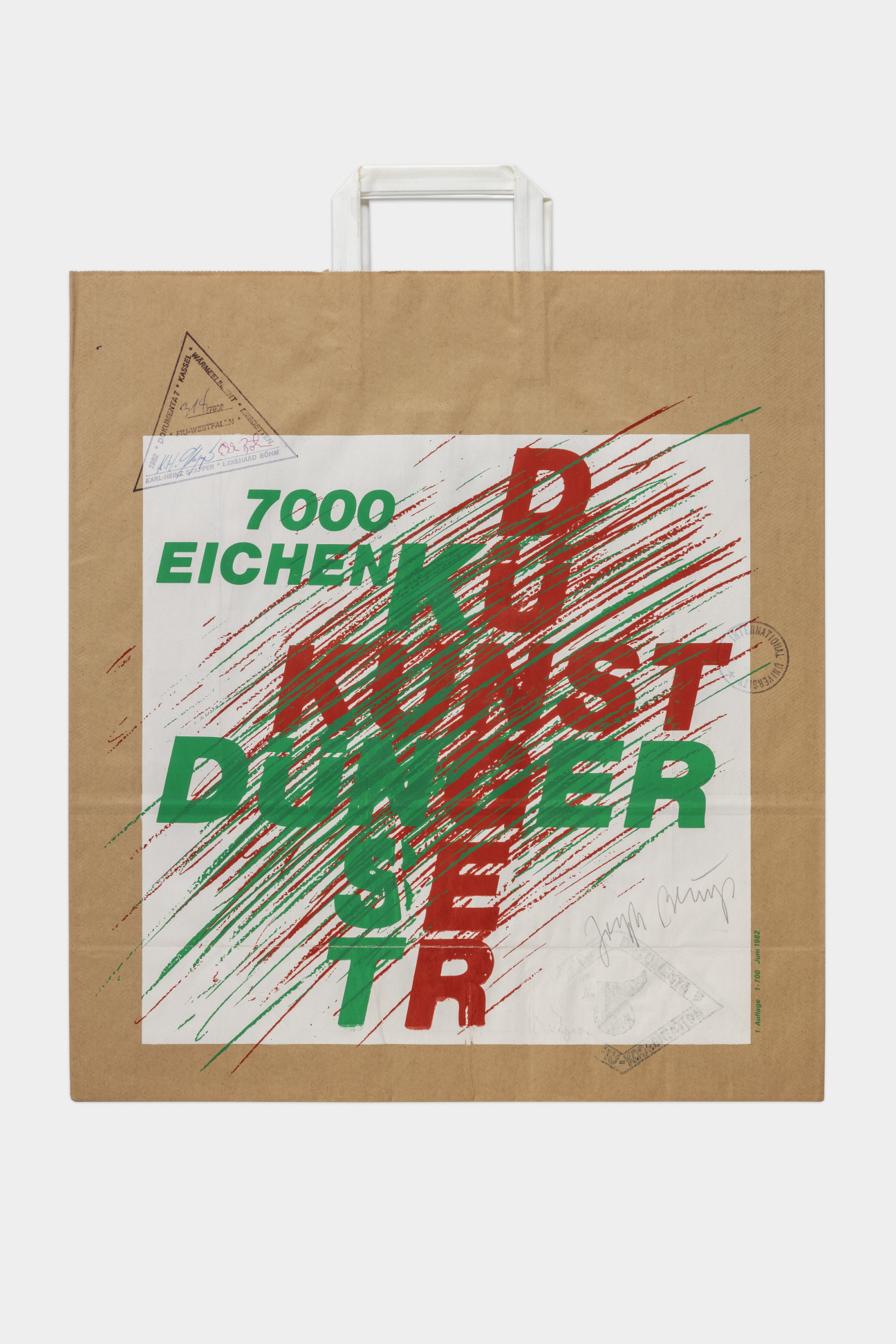

In his last years, Beuys made art by creating life. For his most ambitious work, 7000 Oaks, the same number of trees were planted throughout Kassel, a city then still recovering from the devastation of WWII. Beuys, a pilot in the Luftwaffe during the war, saw this work, along with many others, as his way of healing the wounds he created in the war.

7000 Oaks was started in 1982 and was completed after Beuys death in 1986. Now, the Broad extends the artist’s vision with Social Forest: Oaks of Tovaangar, a reforestation project that accompanies the exhibition. Realized in collaboration with Tongva leaders, the project uses the Indigenous name for the expanse of LA’s Elysian Park where 100 native oak trees will be planted.

I came to know Beuys through books, not exhibitions, which, for me, suits the slow, unfolding nature of his work. Long before I saw his sculpture in person, it captured my imagination through words and images printed on pulped trees. Usually, I don’t read more than a book or two about any artist—too much information can muddy my perception of art—but learning about Beuys has only deepened the mystery.

This is by design. Beuys is an artist of mystery. He fabricated his biography and spoke in a frustrating, poetic syntax. His drawings invoke opaque, metaphysical concepts and his sculptures look like artifacts and relics from an unreal past. In one of his performances, he covered his head in honey and gold leaf and discussed his art with the corpse of a hare, which seemed to be his way of acknowledging the problem of explaining his work to other humans.

It’s tricky to summarize the artist without diluting the complexity that gives the work its power. Across his career, he integrated pedagogy, principles of Fluxus performance, philosophy, political organizing (he was a founding member of the German Green Party), shamanism, and Celtic mythology, all while wearing a fisherman’s vest and a Stetson, as if to suggest that his real work was somewhere out in the wilderness.

“In Defense of Nature” attempts to organize these various elements of his career, but it is challenging to make a sensible whole from his parts. Even after a library of books have been written on him, Beuys still refuses to be explained. For him, art was impossible to be reduced because it is everywhere and we are all artists. This is the real mystery: the vital force, all around us, humming inside all matter. With this suggestion, Beuys’s objects become portals to behold this primordial energy as it flows from the earth to animals to humans and back again.

Beuys loved his materials—felt, stone, fat, honey—and he treated them with reverence. With the presentation of some 400 items from the Broad’s collection, it becomes clear that Beuys, with his immaterial notion of “social sculpture,” did not pursue the dematerialization of the art object as many of his American conceptualist contemporaries did—not exactly. He sought to transcend and democratize it, reframing it as something financially attainable through the editioned artworks that he called “multiples.” A multiple could be a photo, drawing, object (banknote, blackboard), or assemblage. He often finished the work with his signature stamp of esoteric glyphs, or one of his political messages (such as “art = capital”) scrawled in the corner.

One iconic multiple is Capri Battery, 1985: a yellow lightbulb plugged into a real lemon, which needs to be regularly replaced to avoid rotting. It’s an elegant distillation of the energy transference at the heart of the artist’s work. Beuys once said, “If you have all my multiples then you have me completely,” as if he had magically imparted his life force to his objects. If this is true, what would happen if they all burned?

I am not usually a sentimental person, and yet, the total material loss caused by the Eaton fire has felt distinctly like the loss of life. The emotions may be different in magnitude, but they are strangely similar in quality. As with the death of a person, the loss felt is not that of their physical existence but of their presence and what it prompted. Like any good art, my collection of Beuys books added a feeling to my home. When I walked past it, a single glance at a spine could stir up enough mystery to realign my mind for the day.

Throughout the grieving process, people have repeatedly reminded me that what I lost are “just things.” I know this is their way of cheering me up: pointing out the deadness of inanimate objects and the aliveness of my family. I have tried to believe this, but ultimately, I’m not sure if I believe in just things. I lost the guitar my mother gave me before she died. I became a musician while playing that instrument and performed with it in hundreds of concerts around the world. When it arrived to me, it had a name embossed on its back, as if it attained the honor of personhood. I don’t miss the wood and strings, but rather the feeling that the guitar contained. Objects store memory, myth, and meaning, and Beuys knew this well, expressing it with every work he created.

As Beuys says, his multiples express his life, and he began making them early, in 1965, when he was 44. I learned this six weeks after the fire, when I finally visited “In Defense of Nature,” where a timeline traces the trajectory of his life. His career, as we mostly know it, began in his early 40s. Work before this is scant and rarely discussed, and knowledge of his emerging years is mostly built from his own spurious tales. Now, with nearly all my early work and archives destroyed, the first half of my life is, in many ways, erased. Paintings, journals, notebooks, drawings, and childhood work—gone. As I have come to accept this reality, it’s been helpful to remember that in only a brief, late window of working, Beuys created an entire world.

The multiples in the show are quiet and subtle: videos, posters, and prints of drawings, scribbled in the proprietary color he called “brown cross.” Unfortunately, my viewing experience was accompanied by the painful roar of pop music thrumming through the museum. A disorienting mixture of Katy Perry’s “Fireworks,” shrieking, and applause made it nearly impossible to give the nuanced work the attention it needs. When I reached the end of the exhibition, I saw that an aerobics class was being held beside a silent video of Beuys planting his first oak trees.

Here was a reminder of why I sometimes prefer books to exhibitions. I’ve entered much of my favorite art through the page, not through the gallery. An art book allows for an uninterrupted, immaterial fantasy, unfettered by whatever material context a space may give it. So, among the first things I acquired after the fire were some new Beuys books, the first of which was the catalogue for the Broad exhibition.

This book is not a tribute to Beuysian mystery—like, say, Beuys on Christ or The Felt Hat, 1997—but rather a fairly straightforward monograph. Nearly half of the book is dedicated to the Social Forest: Oaks of Tovaangar—not a Beuys artwork, but a fitting and valid extension of his legacy. Beuys knew that trees are healers. They are air purifiers. They filter toxic smoke from urban fires. They lift our mood.

Altadena used to have some of the tallest trees and the cleanest air in the city. This was due to the aquifer beneath the town and the orographic effect of the San Gabriel mountains to the east, which created enough moisture to grow the pines on Christmas Tree Lane and the coastal oaks in Cobb Estate, where the Marx Brothers once lived.

After seeing the ruins of our home, I assumed that all the plant life in the area had been destroyed, but this is not so—countless oaks are alive and well in Altadena, growing through the rubble. Live oaks are native trees, familiar with California fire—maybe even invigorated by it—and they can thrive amid our tragedy. These ancient beings have forged a relationship with fire. How have they done this? How has the Pechanga great oak, not far from Altadena, lived to be 2,000 years old? How have oaks been surviving on this planet for 56 million years, through disaster after disaster? These are true, indelible mysteries, and they are worthy of holding our attention forever.

in your life?

in your life?