Around 2000, just after Sean Baker got clean from opioids, he had to rebuild his life from scratch. He had been tossed from Greg the Bunny, the TV show he helped create that had been picked up by Fox. He lost most of his contacts and had stuck around New York while others from his early film escapades went west. But he thought he could survive one last attempt at becoming a filmmaker. “I did everything I could not to get a nine-to-five,” Baker tells me. “I wanted to stay connected to the industry, even if I was on the farthest fringes.” He edited corporate videos; he duplicated VHS tapes for actors’ reels. And—whether you’re a palm reader or a lawyer or a filmmaker—there is always work in weddings. “I worked for the high-end wedding video company,” he recalls. “Martha Stewart-type stuff.”

Most of the weddings he filmed were in ethnic enclaves of New York. One took place in Brighton Beach, where the Moscow satellite elitism and shitty weather stuck with him. It was an early seed for Anora, his latest movie, which was nominated for a whopping six Academy Awards including Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Actress in a Leading Role, along with six Film Independent Spirit Awards. It also took home this year’s Palme d’Or at Cannes—the first time an American filmmaker has won the award since Terrence Malick in 2011.

The film is about an exotic dancer and escort—the titular Anora, better known as Ani—who grew up in Brighton. After meeting Vanya, the son of a Russian oligarch, she becomes his girlfriend for the week in exchange for $15,000. She then marries him in Las Vegas and is clumsily taken hostage by his parents’ goons while they try to find Vanya, who has fled, so they can annul the union before their bosses arrive on American soil.

“I worked for the high-end wedding video company. Martha Stewart-type stuff.” —Sean Baker

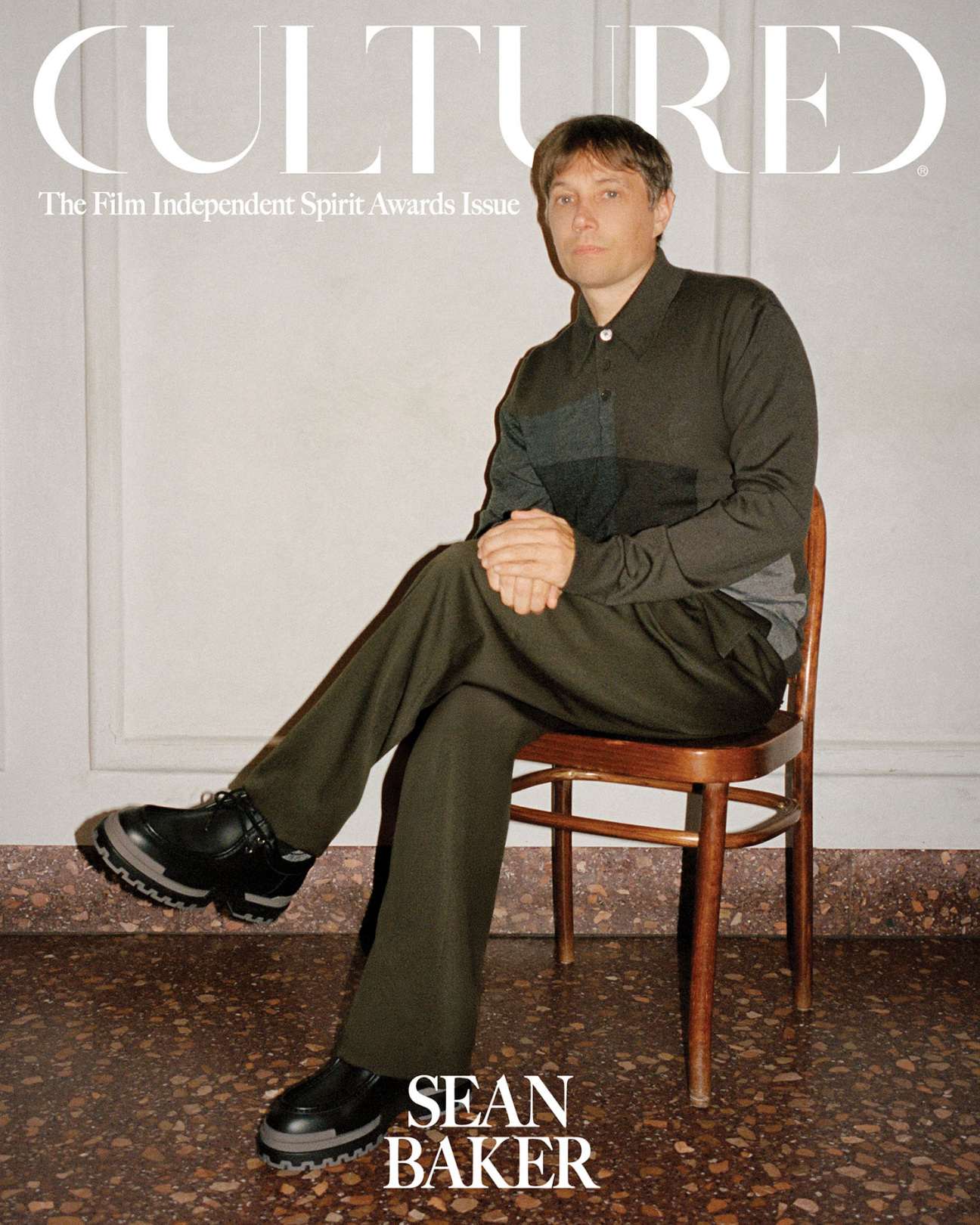

You could call Baker’s work “neo-neo realism,” the term coined by A.O. Scott in 2009 to describe Great Recession-era films that focused on outsider characters, first-time actors, and bare-bones depictions of socioeconomic struggles. But he’s been at it for longer than that. (Longer, in fact, than one might expect—he looks good for 53, like he could do a kickflip if you asked.) Nevertheless, his attempts at that realism, no matter how vérité his shots or how shoestring his budgets, are forever complicated by the simple fact that he is the ultimate insider-outsider: at once fluent in the hustling, addiction-adjacent lives he depicts, and something of a Hollywood voyeur.

When we spoke, Baker was in his New York apartment, jet-lagged from events in London and rubbing his eyes as his dog crawled into his lap. He was bracing for the film’s New York premiere, which he accented with scare quotes—“the ‘premiere’”—as if the pomp was a little embarrassing. Anora’s box office numbers prove that Baker has reached a kind of escape velocity. It doesn’t hurt that Zoomer appetites for chaotic and brash New York fare have been whetted by the Safdie brothers.

Anora is the rare film that features cell phones and vape pens—the key accoutrements of its 20-something characters’ lives—successfully (which is to say, constantly and without much interest). But Baker’s eye developed back in the 1970s, when he would drive into the city from New Jersey with his dad, a time when porn was still shown in theaters. “We would come out of the Lincoln Tunnel and head down 42nd Street. It was a ‘Welcome to the Jungle’ moment every single time,” he told me, with ads for Marilyn Chambers and Deep Throat lighting the way. He has visited various corners of the sex work industry in most of his films since.

Sean Baker is the ultimate insider-outsider: at once fluent in the hustling, addiction-adjacent lives he depicts, and something of a Hollywood voyeur.

Tangerine focuses on Black trans sex workers in LA; Red Rocket is about a washed-up male porn star on the Gulf Coast. Baker consistently, if dutifully, speaks out for decriminalization, but he’s allergic to preachiness and politics. “A lot of our media speaks to the left. I happen to be left-wing, but I think it’s important for everyone to be talking,” he says. “I’m trying to make a universal story that has fleshed-out, three-dimensional, human characters who allow audiences to have empathy. They can apply their own thoughts and ideologies."

Baker calls Anora “high-concept,” since its plot can be summarized in a sentence, but it’s also his most planned movie. Its budget was reportedly $6 million—three times the estimate of The Florida Project—and while his other films achieve their heady tenor through the rough-and-ready chaos of first-time actors, Anora’s central performers are all pros (he was even willing to wade through Russian visa complications to bring a couple of them over). “With me taking more money this time, the risk is higher. I didn’t want to fool around, basically,” Baker muses. “In the future, I’m sure I’ll always have a portion of the cast that’s brand-new, off-the-street faces, but being able to work with professionals changed my game.”

“You have to get embedded a bit. Sometimes it gets to a risky place, whether that’s drugs or something else." —Sean Baker

Fourth-wall breaking in Anora is mostly self-referential: This is the second movie in which the actor Karren Karagulian, a frequent Baker collaborator, drives a car while someone pukes in the back seat. (Other tears in the fabric, like using t.A.T.u.’s “All the Things She Said”—also the Red Scare podcast theme song—in one climactic sequence, made people audibly groan in the theater where I watched it.)

When you build a career on the hustle mindset, the eternal question is, What happens when you become successful? Baker hasn’t “made it” in any consequential sense, since doing so in American independent cinema is essentially impossible—although he’ll probably never have to edit another wedding video. But whether higher budgets and buzz will bring him more scrutiny, or make his art suffer, is another matter.

Most important to Baker is whether he’ll be able to dip back into the jungle for inspiration again. When I asked him about avoiding creative atrophy amid growing resources and comfort, he answered with the frankness of someone who has found himself, at times, in dire straits. “You have to get embedded a bit. Sometimes it gets to a risky place, whether that’s drugs or something else,” he said. “If I pick up anything hard in the opioid world again, it’s suicide. So it is dangerous. But I can’t be writing my worlds sitting in West Hollywood.”

After seeing Anora in Downtown Brooklyn, I cued up “Greatest Day,” the smarmy pop anthem by Take That which soundtracks the fragile joy that blossoms in the movie right before everything goes to shit. I got on the Q train and headed in the direction of Brighton Beach. But I got off before I could get there.

Casting by Special Projects

Grooming by Erica Janssen

Post-production by Matthew So

in your life?

in your life?