Whether you’ve seen a Luca Guadagnino film or not, you’ve most likely experienced their aesthetic collateral. The prolific Italian director has permeated the zeitgeist with a slew of features mining feverish, tangled, and often queer desire. Last year alone, he released Challengers, which chronicles a love triangle between tennis stars, and Queer, an adaptation of William S. Burroughs’s 1985 novella, which follows an American expat as he falls for a much younger man in 1950s Mexico City. Now, he’s at work on six—yes, six—new projects, including a highly anticipated adaptation of Bret Easton Ellis’s 1991 serial-killer novel American Psycho.

Those who have read the book or seen Mary Harron’s early-aughts interpretation starring Christian Bale will recognize the obvious allure for Guadagnino. His films pair lush visuals with emotionally turbulent characters struggling to keep up a once-reliable facade. Style is what the director is chasing, followed by sex. Both exemplify the tension between how we want to be seen and what we want to feel. In Queer, his most unorthodox film yet, the lens tracks Daniel Craig’s hand as he traces it down the body of his lover, played by Drew Starkey. Later, through clever editing, Craig is able to get even closer, moving his hands literally under his partner’s skin as the two men writhe and caress each other’s ribcages for several uninterrupted minutes.

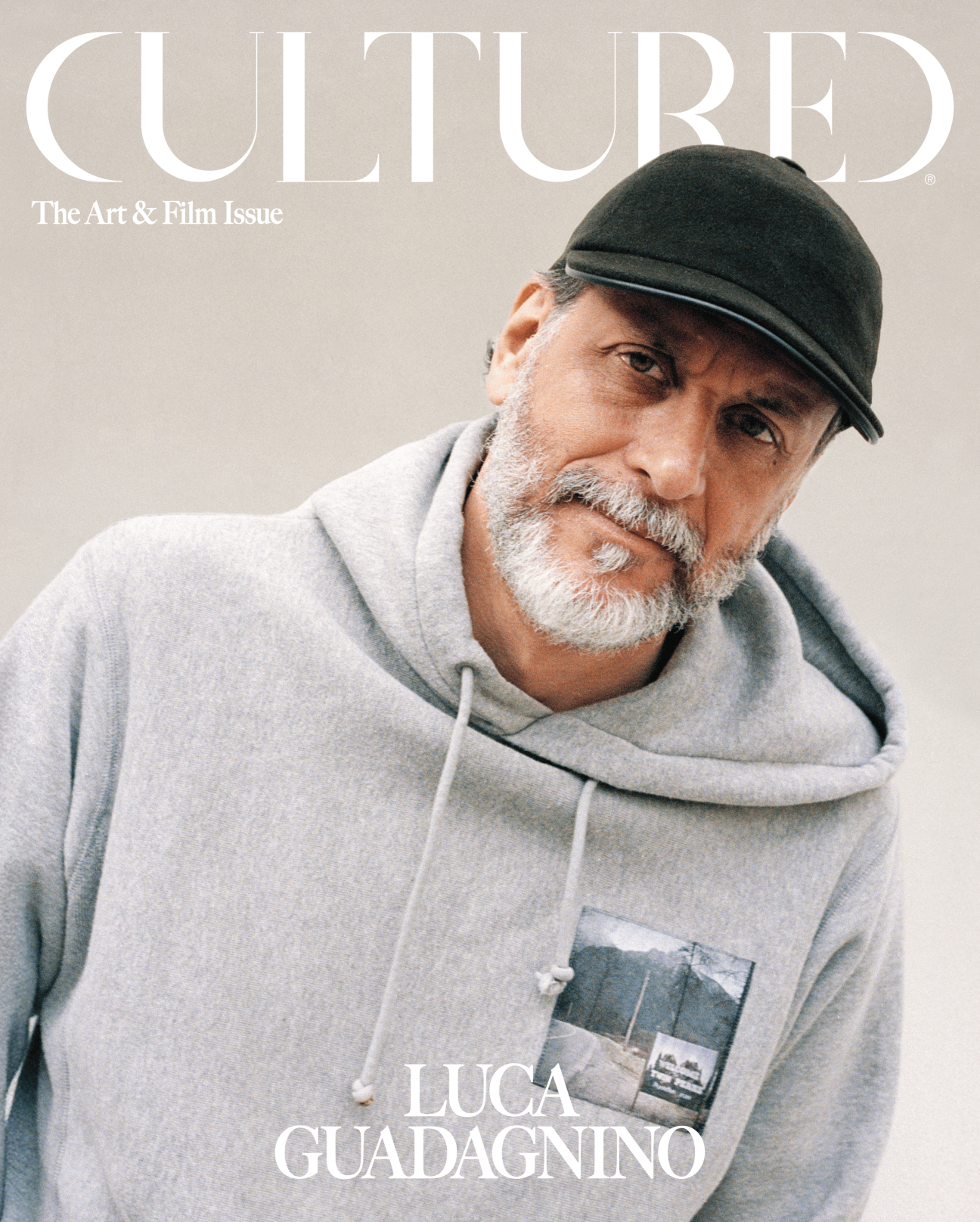

With projects like these, Bones and All, and Call Me by Your Name, Guadagnino has managed to maintain his position as a daring festival darling even after becoming a box office stalwart. His look and feel onscreen is as easy to conjure as Nolan’s or Gerwig’s—a point of view that lingers long after the credits stop rolling.

Guadagnino’s interest in sumptuous texture and color is equally as evident at his home in Alessandria, Italy, as it is on set. Somewhat covertly, the filmmaker has been leading an eponymous design studio since 2017, imbuing Italian apartments and hotels, like the 16th-century Palazzo Talia in Rome, with his characteristic charm (and earning an AD100 nod from Architectural Digest in 2022). He also served as artistic director of the 2024 edition of Italian design biennial Homo Faber. One could easily imagine his characters lounging around the high-ceilinged rooms of his own abode, nestled in a scenic province in the Piemont region.

Though his previous residence was lined with 18th-century Japanese painted panels and John Gould prints, Guadagnino’s eye has turned to his contemporaries; among his art holdings is a work by experimental German photographer Thomas Ruff—a staple in the collections of the Art Institute of Chicago, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Guggenheim, amongst others. Ruff, whose work is on view in a solo show at David Zwirner in London through March 22, made his name in the 1980s for blown-up, full-frontal, and sometimes digitally manipulated portraits, going on to explore everything from military technology to online porn to experiences with mescaline in his work. Despite their formidable scale, his images are often unnerving and intimate, much like Guadagnino’s own art.

“I’m constantly hypnotized by [your] portraits,” the filmmaker told Ruff when the two met for Guadagnino’s Art & Film issue cover conversation. Thus far a private collector, here Guadagnino opens up about his love for art in conversation with a favorite creator, taking us one step further into his immaculately curated universe.

"Is it dangerous for the viewer?" —Luca Guadagnino

Luca Guadagnino: I have utterly admired your work since since I saw [it] many years ago. I want to understand how you see your work as being political?

Thomas Ruff: The answer is pretty easy, because every artist is a human being and every human being has to be busy with politics. So, I would say all the art is political. It’s a strange world we live in, so I’m reacting to this strange situation and I pick issues that keep me busy.

Guadagnino: Yes, particularly in some of the more recent series you created, like the one that plays with the concept of propaganda [“Tableaux chinois,” 2019–present, and “Tableaux russes,” 2021–present]. I also somehow want to put in the same category the beautiful work about pornography that you made [“nudes,” 1999–present]. Are you trying to educate the viewer or to trick them?

Ruff: I always try to educate people. I guess propaganda is so fascinating because it’s a big lie, and lies right now are pretty obvious in politics, and they’ve been obvious in politics since… Let’s go back 100 years. Maybe I grew up in a time, let’s say the ’60s, ’70s, where people could believe in the media, but there’s always been a discrepancy between the official image and the real image. I also want to deconstruct, in a way, these kinds of official images, these official lies.

Guadagnino: Some of the imagery—for instance the use of color in these pictures—gathers an element of the sublime. That is a very beautiful double step in your work between something that you need to think about very closely and with a very strong sense of duty as a viewer, and at the same time, the sublime that your images encompass. The concept of the sublime, to me, participates a lot in the canon of great German artists that I’ve been growing up with and learning about.

Ruff: What I want to do is really correct, intellectually interesting work. At the same time, it has to be very attractive; otherwise, the viewer would not look at it. The sublimity is very decent, so that the viewer doesn’t get it, but is attracted by it.

"I also want to deconstruct, in a way, these kinds of official images, these official lies." —Thomas Ruff

Guadagnino: Is it dangerous for the viewer?

Ruff: No, if he looks precisely and if he uses his brain, he will get a kind of enlightenment moment.

Guadagnino: Going back to the series of portraits [“Porträts (Portraits),” 1981–91/1998–2001], I remember I read a beautiful answer you gave about the moment when this concept started for you and how you wanted to create somehow a portraiture that was a political reply to the idea of being constantly controlled, particularly in your generation. Looking at these works now, [there] is a sort of dimension between me, the viewer, and the person that I’m looking at, which is so big compared to the right proportion. It somehow is asking me to question who I am as a person. Because I’m looking at another person on a scale that is not natural.

Ruff: I’d been studying at the art academy in Düsseldorf [Kunstakademie Düsseldorf]. I was just fed up with all the portrait photography that I knew so far. I really wanted to bring back the portrait to point zero, to eliminate all the conventions that are connected with a portrait and to just show the human face—nothing more. The title was just Porträt, and in the year 1988 or something like that, I even was hiding the name. The name [of subjects included in titles] was given by the curators because people can’t stand it if they have no information about a person they are looking at. Some visitors standing in front of my portraits would become very aggressive. They would ask, “How old is he or she? What is he doing?”

Guadagnino: You just said before that you understood the limits of photography. What are they for you?

Ruff: Photography should not be unsharp, except if it’s the unsharpness of a movement. Photographs should be as precise as possible. At that time, I didn’t want to see any grain; I didn’t want to see the structure of the film or the paper. I want to have the pure photograph. Now, we are talking about the limits. Probably, the portraits were so successful because they were totally different to paintings, but they had the size of painting, and people were really shocked when they saw them for the first time. They had a kind of precision that you cannot paint.

Guadagnino: Because I’m a filmmaker, my last question for you is, what is your relationship with cinema?

Ruff: Pretty often, when I go into the cinema, I’m disappointed. I say, Oh, this was a waste of time. This was such a bad film. I would say 90 percent of film is just bullshit. It’s just entertainment. It has nothing to do with the real world or the issues that I’m busy with. But, of course, I’m always really happy when I go to the cinema and see a good film.

Guadagnino: I think it’s a rarefied experience, one of being met by a serious work of art in any medium, to be honest. I agree with you that cinema, unfortunately, has deprived itself of its own strength for a long time now. But we always have hope, I would say.

Order a copy of the Art + Film issue with Luca Guadagnino here.

Casting by Special Projects

Hair by Armando Cherillo

Makeup by Andrea Severino Sailis

in your life?

in your life?