There’s a postcard display in the Dia Beacon bookstore, by the register. In an especially beautiful image, featuring Nancy Holt’s Sun Tunnels, 1973–76, the Great Basin Desert landscape is cut into concentric circles by a view through two of the steel-and-concrete tubes that compose the monumental work, an off-center sun flare fuzzing out a section of dark horizon. Another photo of a Land art site stewarded by Dia captures the moon rising in a purple sky over the New Mexico plateau where Walter De Maria’s legendary expanse of stainless-steel poles, The Lightning Field, 1977, is installed. I also pick up an aerial shot of Robert Smithson’s iconic Earthwork Spiral Jetty, 1970, in which three people, walking along the coiled path, look like ants.

But I’m here to visit Cameron Rowland’s “Properties,” curated by Jordan Carter and Matilde Guidelli-Guidi, an exhibition that occupies a conventional, white-walled exhibition space in the museum’s Riggio galleries, or so it might seem initially. At the heart of the artist’s show is Plot, 2024, represented here—inside—by a small, shaded triangle on a map. In the surveyor’s drawings of the Hudson Valley property owned by the institution, you can see that it represents a single acre—one of 32. Beginning near the southeast corner of the Dia Beacon building, it runs parallel to a creek, pointing, like an arrow, away from the back of the museum. It can’t be seen from the gallery, which is located near Dia’s front entrance, and no photographs are included in the artist’s stark presentation of documents and just a few objects. I take pictures, though.

Rowland, who is in their 30s, has been exhibiting for only a decade or so, but they have, since the outset of their career, gained attention for their exacting conceptualism, its balance of cryptic gestures and distilled exposition, as well as for the subject matter of their art: racial capitalism. In using contractual relations to unveil institutional histories and complicities—and perhaps especially in making their work unavailable to purchase (the artist negotiates rental and loan arrangements)—Rowland sails against the headwinds. They are something of an anomaly in this era of frictionless transactions, in an art system that rewards thinking small. With "Properties," they further develop the most ambitious element of their largely dematerialized practice. They engage with notions of monumentality and permanence, advancing an expansive vision of reparations—and challenging the very category of real estate—through Land art.

Since its founding in 1974, Dia has been, foremost, a place for thinking big—and for big things. Visiting its Beacon location to see Rowland’s work for a second time, the weekend after Christmas, I stand at the building’s back windows, which flood Fred Sandback’s sculptures—architecturally-scaled volumes and planes, delineated by single strands of colored yarn—with natural light, a poetic lookout from which to view Plot. With the Minimalist’s work behind me, I see, to my left, across the excavated ground of the art center’s massive backyard landscaping project, the forsaken slice of woods that comprises Rowland’s art, its bounds marked by nothing at all. I imagine a wedge of bare trees and gray brush cordoned off, unsure if the work includes the snow-dusted slope in the distance. (It does, the artist confirms later.)

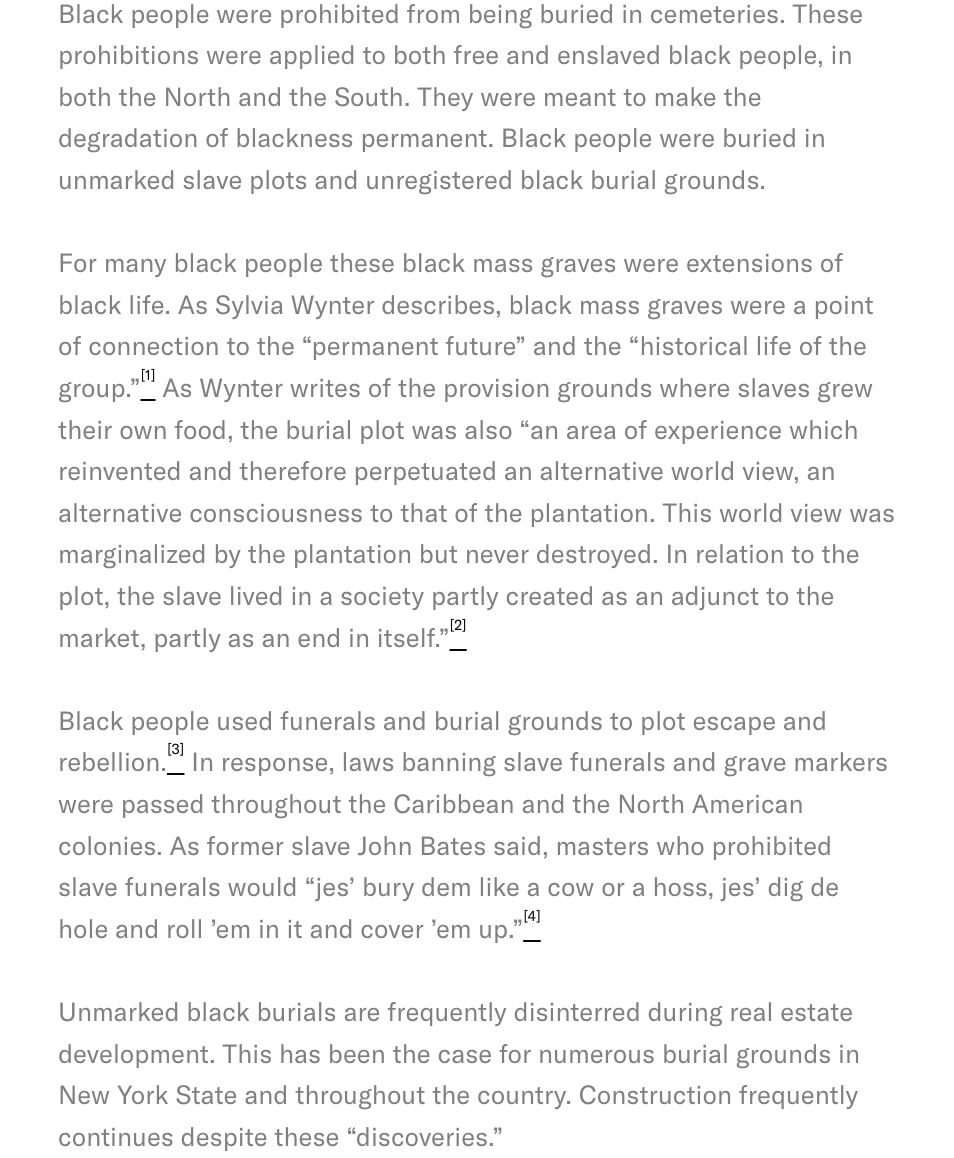

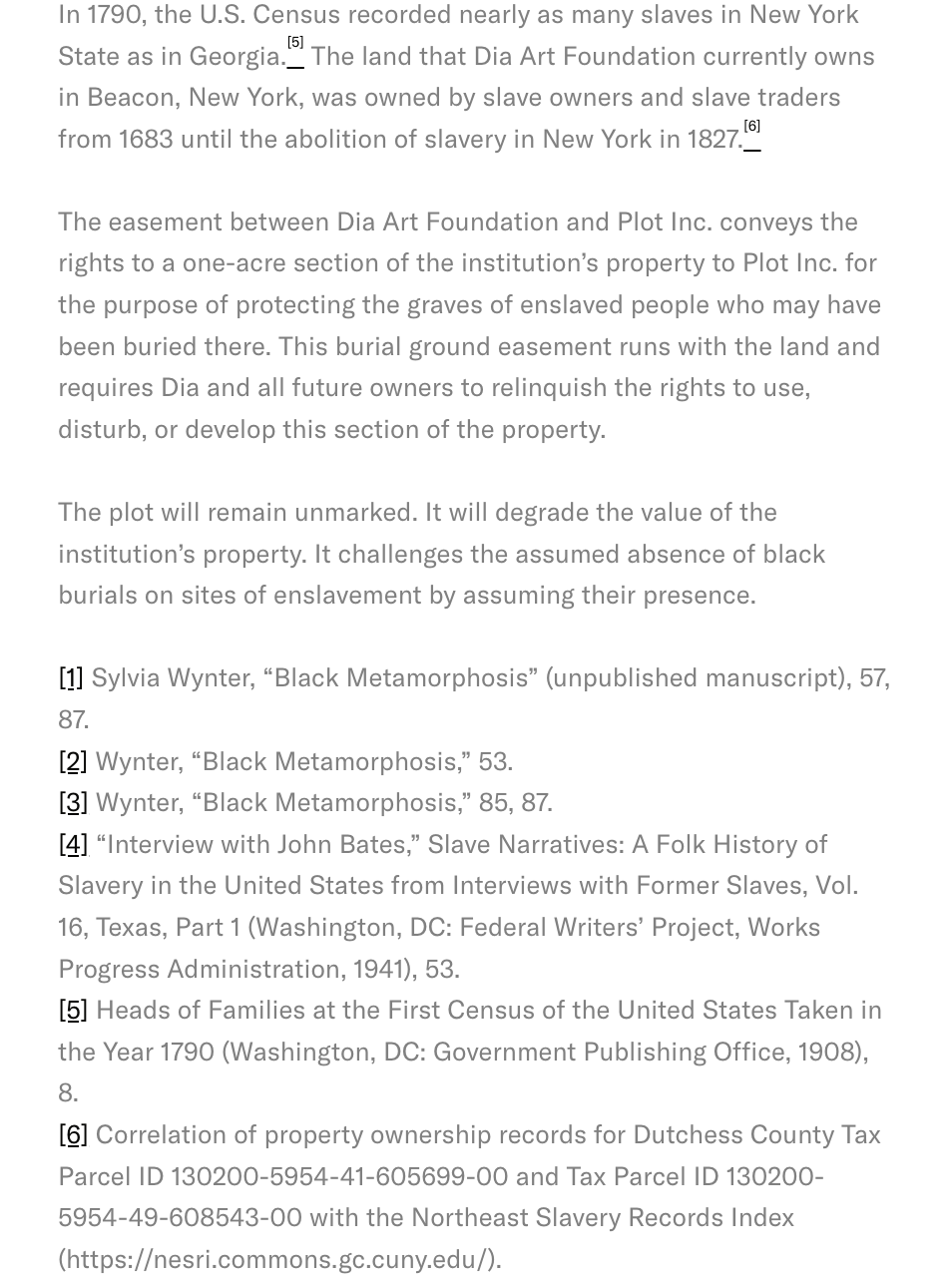

Rowland has designated this small section of the institution’s property as a burial ground—or, more precisely, as they write in the caption for the work in their pamphlet Properties (which is free to take at the exhibition’s entrance), it’s an area preserved “for the purpose of protecting the graves of enslaved people who may have been buried there.” Publicly inaccessible (due to preexisting restrictions rather than by the artist’s specification), the land makes for a strange memorial. And it’s not one—not exactly, or not entirely. It does, or can, function as a spatial catalyst for collective mourning, or as a point of concentration for the cultivation of accurate historical memory. And it can, even from a distance, at least for me, convey the horror of genocide; the strange indifference of nature to atrocity, the way that trees hold still when used as gallows and grow unperturbed from mass graves.

The statement that enslaved people may have been buried here does not, with its asterisk of doubt, mitigate sorrow. Rowland proposes that—given that it was illegal to bury black people in cemeteries; that slave owners forbade funerals; that the disinterment of enslaved and free black people’s remains is common in the course of New York real estate development—we should assume that there are bodies buried in these woods. The work’s significance is not so much fractional—an infinitesimal or symbolic recompense for incalculable harm—but fractal. If you accept Plot’s terms, then any plot, of any size, on land where enslaved people lived or worked, becomes an unmarked burial ground: all 32 acres of Dia’s property in Beacon, all of Beacon, all of New York.

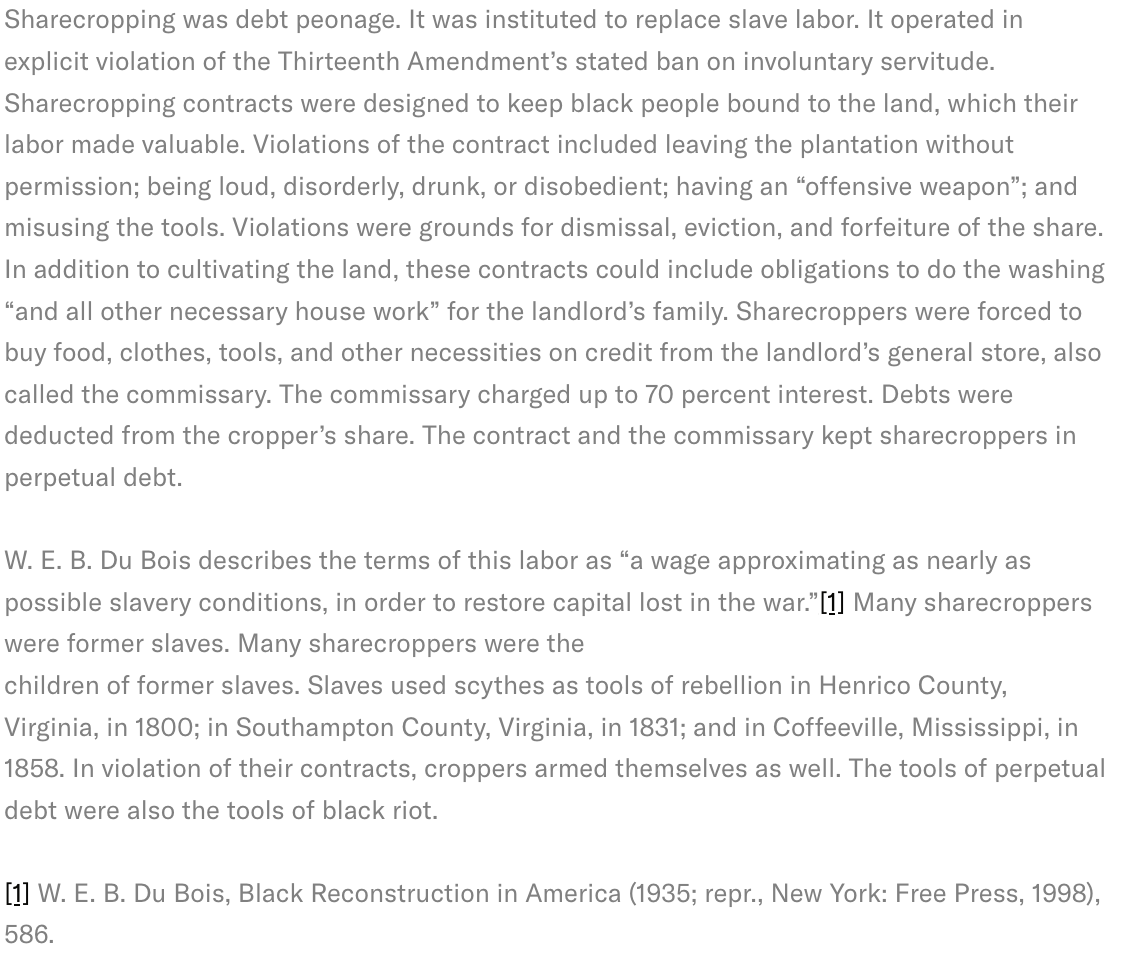

The beauty of the artist’s work—its steely efficacy—lies largely in their carefully crafted captions, which are an essential, constituent part, rather than an accompaniment to, their work. This is to say that any authorized reproduction of Plot (such as the one just above) mostly obviates the need to summarize it: If you’re reading this, you can read the work’s attendant text—and you should. Rowland implicitly engages the entangled lineages of Conceptualism, Land art, and institutional critique via their work’s context, its administrative aesthetic, and its commercially resistant forms. But in their writing, they seem less concerned with joining that art-historical conversation than they are with seizing the institutional and discursive space it has traditionally occupied in order to talk about something else: the events and conditions that must be accounted for in any honest narrative of Western art from the 15th century to the present. Racial capitalism, slavery, and the modes of unfree labor that emerged in this country after the 13th Amendment are methodically pulled into the light by the artist’s blunt, crystalline prose.

The disciplined constraints around the work’s presentation, particularly the requirement to include what might be considered a surfeit of information, is complemented by a strategic withholding of other details—namely, those that concern the artist themself. In a moment when serious artistic practices are muddled or thrown off course by the management of socially mediated micro-celebrity; when the political in art is conflated with the foregrounding of identity, it is—for this kind of radical work—the move to make. Rowland was born in Philadelphia in 1988, lives in Queens, and offers little else in the way of biographical information, underscoring the impersonal character of their activities—such as using legal instruments to enter the truths of slavery into the public record.

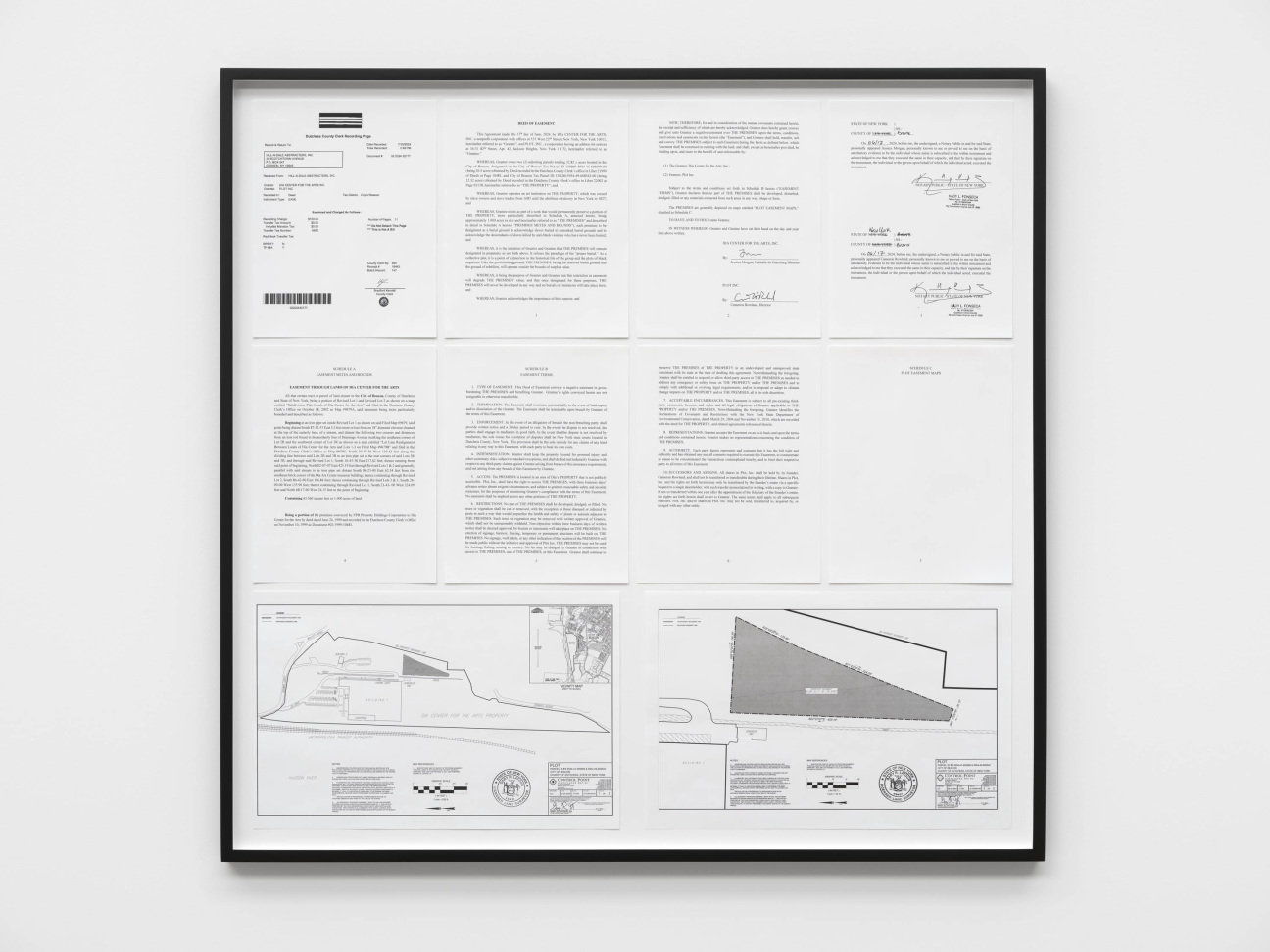

The deed—the official record of Plot’s annexation and special purpose, recorded by the Dutchess County Clerk last July—takes pride of place in “Properties.” At the far end of the almost empty room, the 10-page document, mounted on the wall that faces visitors as they enter, draws them closer until the text comes into focus. (The surveyor’s maps appear in the bottom row of the grid.) It’s an agreement between two entities, Dia Center for the Arts, Inc. and Plot, Inc., an easement that prevents the plot’s use or development, even if the property is sold. In the remarkable legal filing, the grantor (Dia) acknowledges that it occupies land “owned by slave owners and slave traders from 1683 until the abolition of slavery in New York in 1827” and that the easement—this awkward interruption in its 32 (now 31) usable acres—will intentionally decrease the worth of its real estate. ("WHEREAS, it being the purpose of the Grantor and the Grantee that this restriction in easement will degrade THE PREMISES’ value.")

More astonishing perhaps is the agreement’s additional, explicitly articulated theoretical-ideological content. Embedded in it is a short, dense passage stating that the site “refuses the paradigm of the ‘proper burial,’” elaborating that, “as a collective plot, it is a point of connection to the historical life of the group and the plots of black negations.” Furthermore, the plot, “being the reserved burial ground and the ground of rebellion, will operate outside the bounds of surplus value.” This is best parsed, I think, with Rowland’s contextualizing captions in hand, with their steady explanation and citations of black radical thought to illuminate it. But, thinking of a future reader, decades or a century from now—a researcher, a bureaucrat, a lawyer presiding over the liquidation of the Foundation’s assets, or a developer considering a purchase of the land—maybe these lines will achieve their intended effect as something of a riddle. Maybe it will be enough to observe how the wordplay—the close deployment of two senses of the word “plot” (as in both gravesite and secret plan), followed by a literal and then a figurative use of “ground” in quick succession—delivers this acre, with contractual authority as well as incantatory momentum, to an exhilarating place, beyond “surplus value,” free from capitalism’s terrible raison d’être.

I’ve started with the show’s complex centerpiece, but there are stops along the way to the conceptual denouement of “Properties,” on the short journey to the gallery’s far wall. A group of antique objects includes an overturned stock pot placed on the floor by the gallery’s entrance (easy to miss until you turn to leave); a rusted bedframe pushed all the way to one side; and, opposite that desolate domestic item, a row of five scythes. The tools, worn from use, are propped against the wall, rusted blades down.

Readymades have figured in Rowland’s practice from the start, though the objects have not all functioned in the same way. In their 2015 exhibition “91020000” at Artists Space, named for the gallery’s customer number with the state-run, prison-labor company Corcraft, the artist displayed products manufactured by inmates—a desk, fire suits, and courtroom benches among them. Each was exhibited as the fruit of the 13th Amendment’s carve-out for slavery and involuntary servitude (which allowed these abominations to be used as criminal punishment), and as the material culmination of an unsettling connection between the not-for-profit art institution and the vendor. The more recent Ingenio, 2023, shown in the artist’s exhibition “Amt 45 i” at the Museum of Modern Art in Frankfurt, is composed of a colonial-era sugar kettle. The mammoth cast-iron basin not only emblematizes the torturous non-stop work associated with boiling cane syrup—and the enslaved lives destroyed in the process—but also, with its oxidized and worn patina, it speaks of the longevity of the sugar plantation’s brutal methods (some 400 years, Rowland’s caption notes).

In “Properties,” the artist also enlists the aura of the artifact with their choice of objects, but their exact provenance is unclear, the nature of their relationships to slavery and post-1865 unfree black labor left intentionally open. Their purpose seems both semiotic and scenographic. Hailing from an indistinct past, they efficiently periodize an era of black life and labor without a decisive end. And because they are types, un-special representatives of categories—the pot, the bed, and the scythes, belonging to the kitchen, the living quarters, and the field—they begin to read as 3-D pictographs, signs in a notational language that can mark sites of violence and exploitation or become the means of sabotage, refusal, and riot. A pot right-side up is a quotidian prop of domestic servitude; upside-down, it symbolizes the persistence of slaves’ clandestine meetings.

Plot’s caption, as you may remember, likewise rejects a purely violent or tragic valence in its discussion of the black burial ground, citing its collective meaning and its use as a place to plan escape. If my wintry photo of it, and my thoughts looking through the window, are bleak, the artist’s own picture, which they send me after we talk, reminds me of the site’s changeability—how it can look different and hold other meanings. Shot standing on the ground, at the base of the triangle, looking south, the image shows a sunny, early autumn day, the leaves just beginning to turn. In this light, it is easier to understand Plot as not (only) a place of sadness, but as “the ground of rebellion,” as the deed reads.

The historical “plots of black negations” that Rowland references—the tradition of property destruction and counterproductivity that their art joins—have not been recorded in racial capitalism’s grand ledger. Nevertheless, they have eaten away at slavery’s spoils, exacting reparations on their instigators' own terms, in countless ways. The results of Rowland’s plots (Plot's degradation of the value of Dia’s property is just one example) are, gratifyingly, finally, officially counted; they will register, “in perpetuity,” as losses. This un-bleak field of activity, what the artist sees as an expanded field of reparative experimentation beyond the reallotment of capital or real estate, is of primary interest to them. (The field of art is a place to think it through.)

Appearing in such a spare presentation, in such a large space, Rowland’s readymades in “Properties” look small and somewhat adrift—I hesitate to say misplaced. The gradual waning of the Duchampian gesture’s original effect, as it has been extruded through Conceptualism and Pop, commodity sculpture and institutional critique, means that with the snap of a finger anything can look like art and appear perfectly at home in a museum. But Rowland’s extremely allusive objects, freighted with narrative and symbolic potential, do seem slightly ill at ease or unwelcome in this particular art context—or perhaps they are themselves low-key standoffish. Perhaps, in Rowland’s small-m minimalism—in their sculptures here, which touch both wall and floor and eschew pedestals like the nearby objects of the big-M titans on permanent view—there is a streak of mockery.

Sawtooth skylights provide the partitioned, interior spaces of Dia, a former Nabisco box-printing factory, with the diffuse natural light fundamental to the building’s magic. Something of a high-modernist temple with its industrial proportions, the museum is the institution’s flagship exhibition space for its preeminent collection of Minimal and Conceptual art. In recent years, it has also occasionally become a space for the contestation of those movements’ blinkered pretenses and sprawl, as well as for the critical revision of an almost entirely white-male canon—one that was established, in part, by the institution’s own collecting habits. Dia acquired its first works by black artists decades after its founding—Charles Gaines in the 2010s; Sam Gilliam in 2020. Even more recently, major works by Senga Nengudi, Jack Whitten, and Melvin Edwards were added.

The rooms filled with Edwards’s works, from 1970/2022—which I walked through as side-trips on my visits to see Rowland’s show—form an oblique and elegant critique that proceeds as a mazelike series of obstructions. Edwards used a common, industrially produced, non-art material, as his Minimalist contemporaries did, but he chose one that simply cannot be divorced from its associations: barbed wire. The effect—volumes and planes drawn in real space, like Sandback’s—are room-spanning interventions that inexorably evoke the latent violence of the property line, the active violence of the carceral state.

Dia’s problem—not one of mere representation—was addressed frankly in director Jessica Morgan’s public letter of June 5, 2020, which joined a flurry of institutional statements produced in response to the protests and riots following George Floyd’s murder. (These are striking texts to revisit as museums shed such avowals, per the relevant new Executive Order. According to a spokesman, “The National Gallery of Art has closed its office of belonging and inclusion and removed related language from our website,” the Times reported Friday.) But if Dia is in the same boat as many museums in terms of its embarrassing record of exclusion, it is also different in some ways. Among the self-interrogating bullet points of Morgan’s letter, there is this question, which underscores the issues raised by Dia’s unique collection: “How will we acknowledge the history of settler colonialism and indigenous oppression at all of our sites, particularly our Land art works, and work toward decolonization?”

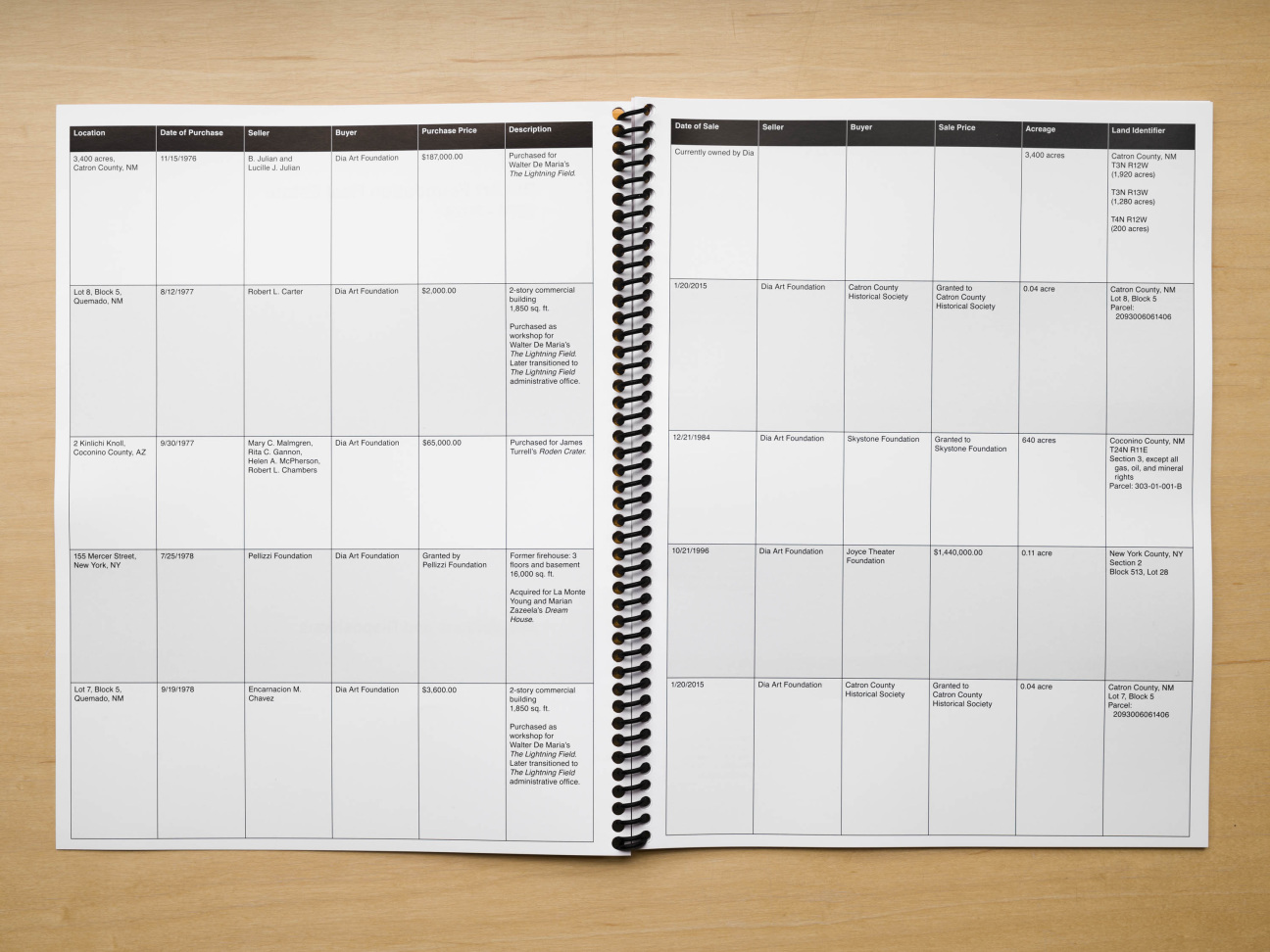

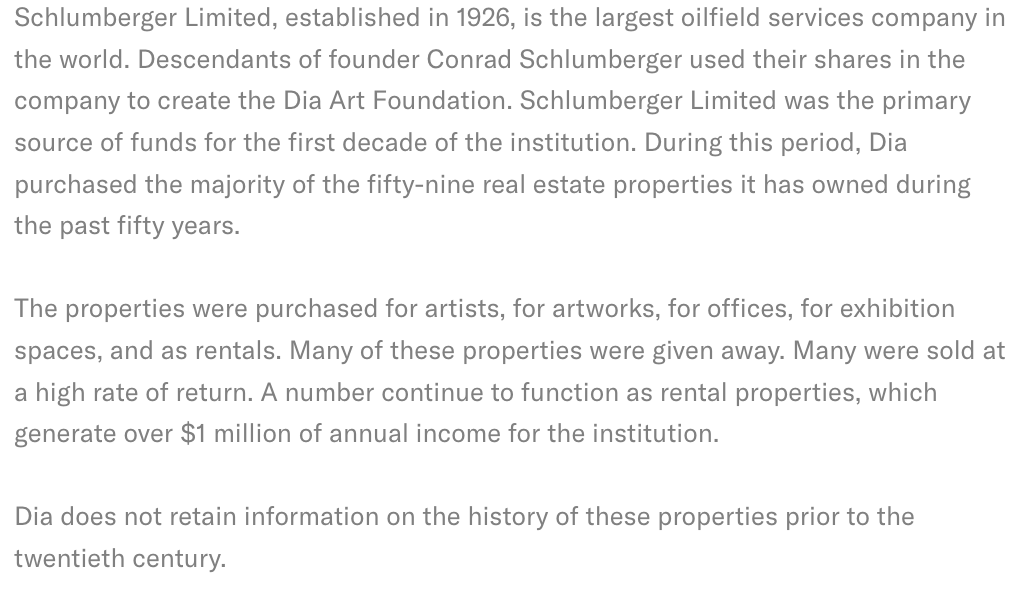

Rowland expands the question of Dia’s Land art sites to its real estate holdings in general with Estate, 2024, an unlimited multiple (a slender, spiral-bound book) on sale for $10 in the bookstore. “Dia Art Foundation Real Estate, 1974–2024,” its plain cover reads. The work appears without fanfare (or attribution) on a table that also displays—among other things—monographs by Sandback, Edwards, and Steve McQueen.

The findings of Estate are presented without comment as a list of acquisitions and dispositions—I won’t spoil it for you by telling you the Foundation’s profit on various Chelsea real estate deals. What I found more fascinating in this stripped-down fairytale of accumulation, were other entries, like those indexing the thousands of acres acquired “to ensure that nothing is built within the visible distance of Walter De Maria’s Lightning Field.” Such information puts Rowland’s single-acre statements into fresh perspective.

Plot is not the artist’s first Land art endeavor, nor does “Properties” mark their first negotiation with Dia. While it’s not shown among the postcards by the register, if you look online at Dia’s site list, which includes the Land art works that the foundation stewards, you’ll find Rowland’s Depreciation, 2018. Represented by a cover page of a property appraisal report, showing a Google Maps-ish photo of roadside brushwood, it’s the penultimate entry, just before Spiral Jetty.

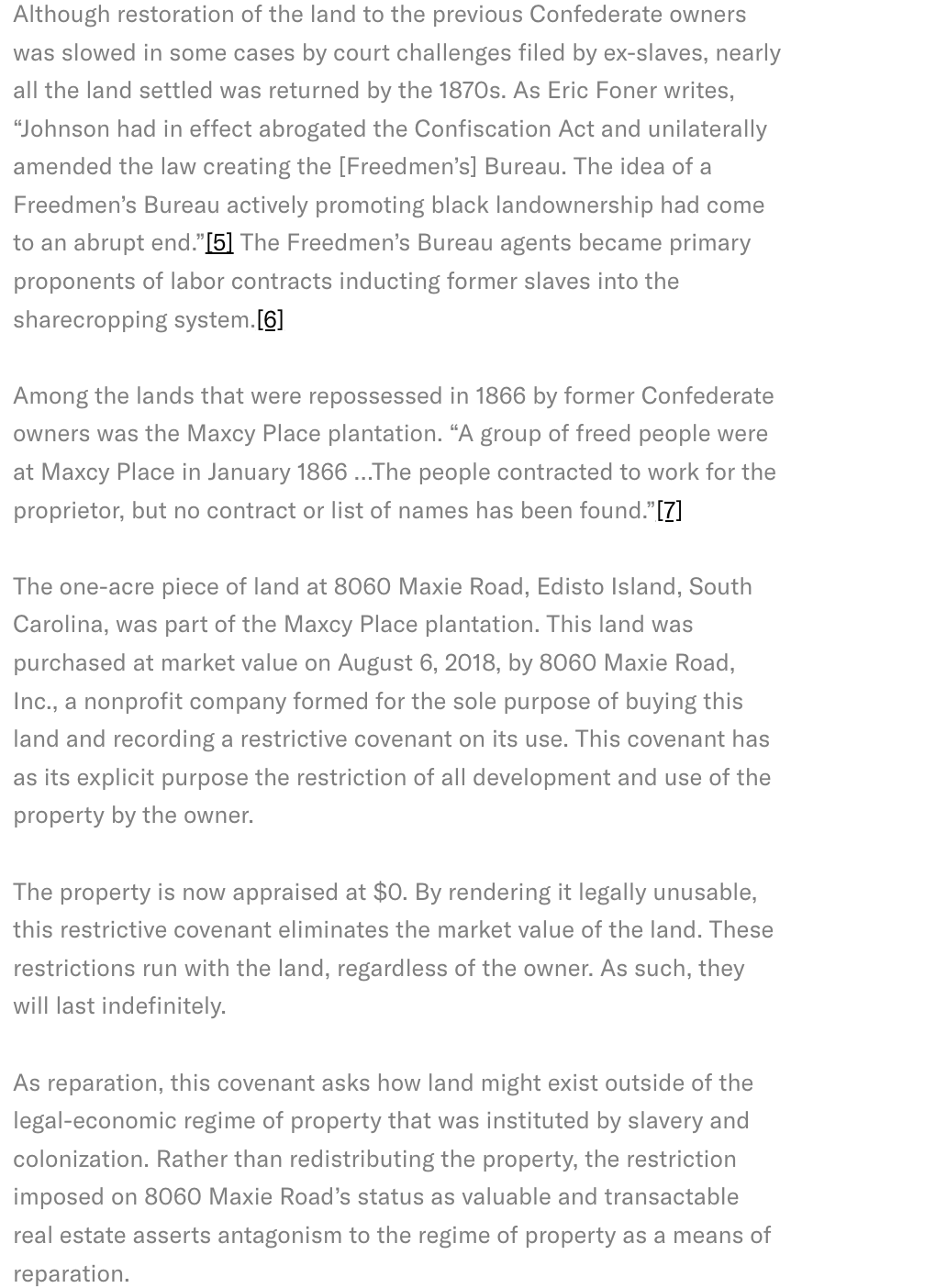

As in much of Rowland’s work, there is an allegorical character to the transactions chronicled in the work’s caption. South Carolina’s Edisto Island, Rowland tells us, is a site of reneged reparations. Part of the territory identified in General Sherman’s Field Order 15 of 1865—which was to be reserved for ex-slaves, each family to be granted 40 acres—it was returned to Confederate landowners in 1866. In Depreciation, the present-day address of 8060 Maxie Road, a one-acre parcel of land that was once part of the island’s Maxcy Place plantation, becomes the site of another negation—real as well as symbolic. Using a legal mechanism that functions similarly to the easement in Plot, Rowland (after creating a nonprofit company for this sole purpose) recorded a comprehensive restrictive covenant on the land, thereby eliminating its value (as indicated by the subsequent, presented appraisal).

Joining Dia’s Land art works in 2023 as an extended loan—Rowland did not sell it to the institution—Depreciation thwarts any reassignment of value to the unusable land through its status as an artwork; it is not an asset. And while that arrangement is aligned with the anticommercial desires of 1970s Land artists to find alternative ways of operating beyond the gallery system, Rowland’s unspoken critique of their approach is sharp.

Visions of the sublime, reflected in photographic representations of the epic undertakings of Smithson et al. rub shoulders uneasily with the historical-materialist humility of Rowland’s appraisal report as they appear together in Dia’s list. The Westward expansion of the earlier Land artists echoes the colonial delusion that unsettled land is “empty,” that the desert wilderness of the American Southwest is a blank slate—open space for formal experimentation on the grandest scale. In Rowland’s Land art, whatever else land may be, however else it might be described, it is real estate, a category defined by the nation’s founding crimes.

Only a week ago I would have concluded on that note. Consider this a postscript of sorts. It may soon be out of fashion, too cumbersome, too much of a liability—or simply illegal—to sponsor or steward such radical art. Institutional favor may dry up; conditions are changing dramatically as I write. But Rowland plays the long game; their work (though not their career) is better equipped to withstand political vagaries than most. As long as the current property regime stands, which is to say as long as the capital extracted from stolen land and slavery still grows, the artist’s negations—the contractual obligations and constraints of their plots against property—will hold.