“Opium for the people.”

That’s how Todd Gray remembers beauty being described during his time at CalArts. The Los Angeles native studied first under John Baldessari and Doug Huebler in the 1970s, then a decade later, with Allan Sekula, Catherine Lord, and Mary Kelly—all fierce interrogators of visual culture’s parameters. Classical beauty was out, critique—socio-political, institutional, aesthetic, economic—was in. “I pretty much held onto that mindset,” Gray recently remembered over Zoom, “until I spent time in Ghana.”

The artist first ventured to the West African country to shoot a music video with Stevie Wonder in 1992. By that time, Gray had two decades of experience as a music photographer. He had toured with the Rolling Stones, worked as Michael Jackson’s personal photographer, and left his mark on dozens of album covers. In Ghana, where he and his wife would eventually build a second home, he began to question his art school education. “I realized I couldn’t process everything solely through a rational thought process,” he tells me. “I wanted to recapture the joy of photography, which was predicated on beauty… I want that element of joy in my work, even if it’s masking horror.”

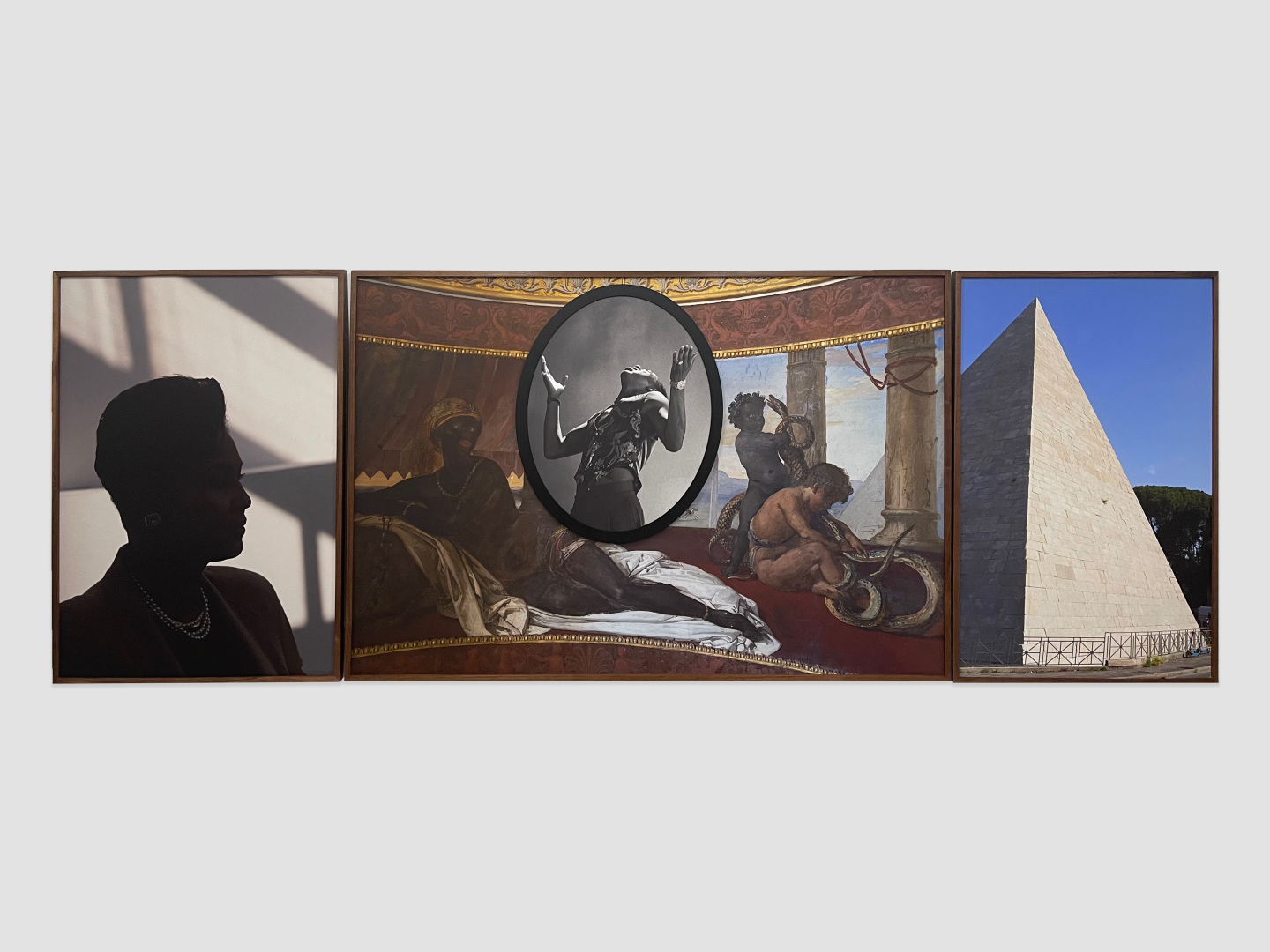

That tension is at the core of Gray’s first solo exhibition with Lehmann Maupin, on view in New York through March 22. Titled “While Angels Gaze,” the show brings together the now 71-year-old’s most recent photo assemblages. Bridging time periods, subject matter, and the artist's different “selves,” each work functions as both a personal palimpsest and a philosophical inquiry—into the persistence of idolatry, the aesthetic collateral of colonization, or the perceived purity of nature. That quality Gray once saw as verboten—beauty—is everywhere in these pieces, but he wields it pointedly as a preliminary invitation for the beholder, “the first utterance” of engagement with the work. Below, he discusses what comes next.

CULTURED: What headspace were you in while creating the most recent body of work on view in “While Angels Gaze”?

Todd Gray: The effect of winning the Rome Prize and spending six months in Rome at the American Academy has had a much larger effect on my work than I thought it would. Over the last year, I keep going back to the images I accumulated in Rome and finding different ways for them to resonate with my thinking. That revealed something to me.

It also opened up the conversation with my “Shaman” series, which I was working on around 2000 to 2007. I was surprised by how much I leaned into that and brought it into the current [iteration] of my practice. Maybe it’s being surrounded by ancient history. In Rome, the idea of time shifts radically. The contrast between the ancient and the contemporary is really salient because, as you walk through the city, you’ll see contemporary architecture next to ruins. That relationship reflects in my work. Maybe unconsciously, it pushed those temporal relationships to the forefront for me.

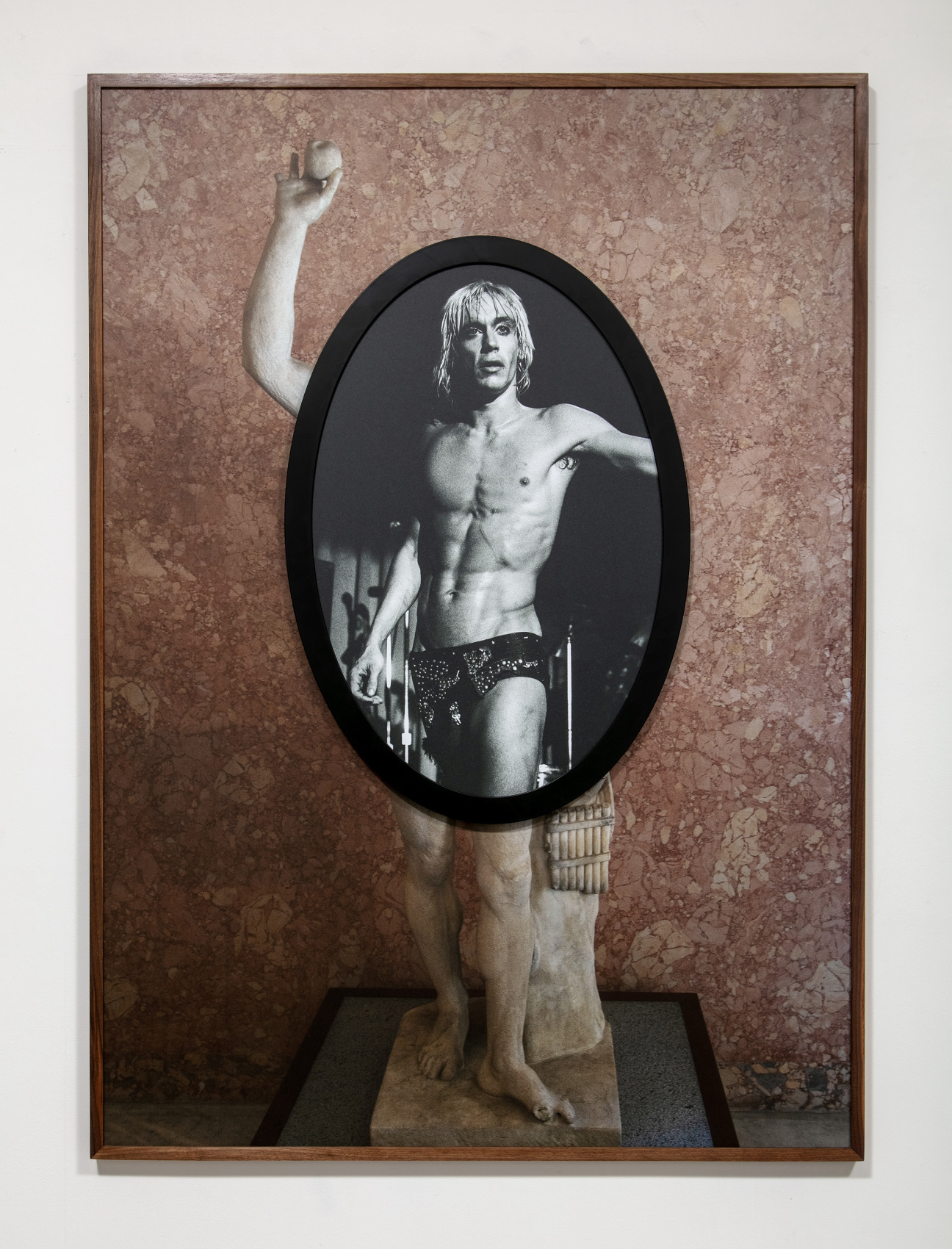

There’s always a layering in my work—a conceptual and visual layering. When people first engage with my art, it’s the beauty that draws them in. I lean heavily on my technical training to create that initial dialogue with viewers. Once you get past that, you start noticing the shifts that happen through the rhythmic changes in how I place forms—circles, ovals, and rectangles—together. This creates foregrounds and backgrounds that aren’t just sculptural but also become temporal.

CULTURED: I want to dwell on the idea of beauty in your work. Beauty, especially within the Western canon of fine art, can be both a gift and a challenge. You’re working both within and without that canon, incorporating influences like music photography and your relationship with Ghana. How do you ensure the viewer engages with the work beyond beauty as an entry point and guide them to dig deeper into the conceptual layers?

Gray: I use beauty in a discursive manner. I like to get close to symmetry and then create an irritant. At first glance, it may appear to be symmetrical, but then something’s not quite right. I like to create what I call an "itch" in the viewer’s mind. Some will see it immediately, others won’t but will sense that something is off or unsettling. I’m really interested in starting a dialogue with the viewer. A photograph is primarily used as a statement of fact. What I try to do is disrupt that so the photograph becomes a question. When you first look at it, it appears balanced, homogenous, or cohesive. But the more you engage, ruptures of time emerge.

Barthes said that the photograph denotes, but as humans, we have to create meaning—we connote. I realized at one point that the act of connotation occurs in a millisecond, often unconsciously. It ties back to our fight-or-flight instincts—we need to identify what we’re looking at immediately for survival. That need for certainty is hardwired into our brains. I use all my knowledge to disrupt that mechanism, making viewers aware that they’re creating meaning. It’s not solely being transmitted by the photograph—they’re participating in constructing it. That awareness is key.

CULTURED: Let’s return to your idea of the “itch.” Who have been interlocutors or conversation partners—artists, filmmakers, musicians—who have created that for you?

Gray: Early Dadaism and John Heartfield were a big influence. Baldessari, because his work leaves you just wondering. Miles Davis. And then, of course, some of the anger that comes out, that’s through hip hop. The visual language that I have is really sonically influenced through hip hop because of the cut-and-paste, the pastiche.

CULTURED: Like sampling in a way.

Gray: Yes, but I’m adamant that I’m sampling from myself. Or my selves. I’m a completely different person than I was in my teens, my 20s, my 30s, or even my 40s. Now I’m in my 70s, and I’ve been borrowing from different aspects of time in my life where my point of view has changed or my thinking has evolved. Frantz Fanon was one of the first writers to make me question how my thinking is organized and to make me aware that I have a colonized mind. He, along with bell hooks, made me take steps to decolonize my mind. Then there’s Stuart Hall. His concept of hegemony—how it’s pervasive and all-encompassing—taught me that our power acts in resisting it and asking "why?" and not surrendering to normative thought or behavior. I applied that to photography, and that’s how I came up with structuring it as almost like low-relief sculpture.

CULTURED: You’re talking about the why of it all, and I wonder what you ask yourself first when you’re starting a work?

Gray: It’s super, super selfish—as I think it should be. I want to make something I’ve never seen before. I want to be awed. Oftentimes it’s very frustrating because I’m making things that don’t awe me. I’m searching for that hit, that exhilarating feeling of seeing something and thinking, I’ve never seen that before. But I’ve learned not to try to create something specific but to return to my archive casually and let my mood and psychological space at that moment determine what I’m going to fixate on. There’s one thing I know: if you have a really strong image, you can build on that very easily. So I’m looking for this strong image … I’ll tell you, when I started using images of Iggy Pop and Michael Jackson, that was super, super tough because they come ready-made as strong cultural reads.

CULTURED: There’s a lot of baggage that’s associated with them from the get-go. The jump from denotation to connotation is instantaneous with a celebrity. How did you move past that initial difficulty and actually incorporate them into the work?

Gray: I had to work with my discomfort. I thought, If I’m uncomfortable, there’s something there. That discomfort means I’ve discovered something that is not normal, and that points me in the right direction—questioning normativity—because I’m making these alliances that don’t sit well together. That’s what creates this discomfort in me. When I made The Song Remains (assumptions about the nature of time) [2024] I put the picture of Iggy Pop on top of the Roman sculpture, and I thought, Oh, I’m just going to go low culture. How can you go lower than punk? And if you’re going to go punk, how can you go lower than Iggy Pop? Then the bodies [of Pop and the sculpture] merged, and I realized later that there was a pan flute in the sculpture. I said, “Oh, this figure is a musician. He’s an idol. This is mythical.” That opened up the idea that these idols are something we need as humans.

With Michael Jackson, it was tougher because how he’s perceived depends on the generation. When you look at him, you might read him as Black, as white, as a child molester—which he wasn’t convicted of—and so forth. I didn’t want his presence to kidnap the entire reading of the work. But then I saw this one shot and that his shirt had the same qualities as that saint. And that’s when I realized, Oh, that’s a technique that’s been used. A spectacle to seduce the crowd into worshipping or following the lead of that individual. But then, of course, I had to have that other figure on the right who was being tortured, which could also [refer to] Catholics torturing throughout the ages.

CULTURED: Speaking of worship, I wonder if you could tell me a bit about your relationship to the angelic. This show is called “While Angels Gaze.”

Gray: I see angels as signifying the Catholic ideal—the highest form that we might aspire to achieve during our time on Earth. It’s positive and pure, or so they say… I was raised Catholic, and I came to recognize the contradictions in Catholicism when I was studying to be an altar boy. That’s when I left the Church. “While Angels Gaze” [points to] the contradictions [within] Catholicism. The angel is pure and innocent, which is why there are so many baby angels, but look at all the actions that have been produced through the institution of Catholicism. It supported and benefited from slavery. It supported colonization on so many continents to solidify its rule. The accumulation of wealth in the Vatican is just unheard of. And yet, outside the Vatican, there are priests asking for money to help their missions in South America, Africa, or elsewhere. Angels are supposed to represent one thing, but even the Church doesn’t follow the ideal of the angel it tells us to follow. While angels gaze, hell is set loose on Earth.

CULTURED: Earlier, you mentioned wanting to start up a dialogue with your viewers. I’m wondering if, in your exchanges with your audience, there’s ever been a reaction from a viewer that has surprised or provoked you.

GRAY: About a year ago someone got upset that I was being critical of the Catholic church, and they communicated that to me. I just responded, “Well, I’m trying to be factual.” And I remember an earlier [work] involving Michael Jackson, where I did this wall collage with a photograph of someone I took at a Michael Jackson concert. The person is looking directly into the camera, and I placed the image so it’s touching the floor. Viewers had to crouch down to really look at this Black person staring up at them. Two people at the exhibit came up to me and said, “Man, I just can’t get my eyes off that person on the floor.” I think it resonated because it addressed being “underfoot”—literally being under the boot. It was about the social status of being pushed down so hard that viewers, from their higher position, had to look down and confront it. For me, moments like those are positive. They show that people aren’t just looking and walking away—they’re arrested by the image. Even with my oval [frames], I sometimes tilt them slightly. As a Virgo, I want everything perfect and balanced—I’m a control freak. I know some viewers with that same tendency will see those slight tilts and feel compelled to spend more time with the work.

CULTURED: This is your first exhibition with Lehmann Maupin since joining the gallery. I’m wondering how you want this show to be remembered in your career?

Gray: I’m just really happy to have a platform like Lehmann Maupin. The gallery space is fantastic for the scale of my work. I want to throw down and make a mark—that’s my immediate response. But I must say, in parallel with this, I’ve been working on a piece for the past several months, a commission for LACMA. They’ve commissioned me to create a 30-foot work that will be permanently installed in their new building. When you walk in, it will be the first piece you see. And there’s another thing. Coming from LA, from Hollywood, the way I’ve resisted using my celebrity archive feels relevant. In the fine art world, celebrity culture isn’t taken seriously. As a maker, I never let the fine art world know I was a commercial photographer because there’s this line in the sand. You wouldn’t be taken seriously if they knew. That’s been one of the hurdles I’ve had to overcome to make this work—letting go of that stigma. I’ve had to realize that this hierarchy of high art versus low art, pop culture versus fine art—it’s artificial. Something I’m embracing now is the idea that my work feels very West Coast, very Los Angeles. Had I not gone to CalArts, I wouldn’t be making this art.

CULTURED: Todd, what do you make art for, and what do you make art against?

Gray: I make art to please myself—for pleasure. I make art because it makes me wonder. I make art to talk about the time I’m in. I want the work to mirror the times as I see it, so that my voice is heard. I feel that my voice is present because I stand on the shoulders of so many people who have passed before me. I have a responsibility to speak whatever truths I experience. When I was going to grad school, I used to read slave narratives. It really empowered me not to succumb to the barriers I was confronting or the emotions of frustration. I thought, Hell, man, look at all the people that have suffered and are no longer here. You’ve survived. You’ve come from this stock. I know the sufferings that have happened before me allow me to be in this position, and that creates a huge sense of gratitude because I have a voice and a platform. I take that very seriously, but I also want to have fun. And I definitely want the work to stir the pot.

in your life?

in your life?