This is Street Smarts, a new column from art advisor Ralph DeLuca that offers art world veterans and newcomers alike a straight-talking, no-bullshit guide to the aloof and difficult-to-crack contemporary art market.

In 2024, the art market experienced a significant correction, marked by a decline in prices for emerging artists, the closure of numerous galleries, and the advent of a totally new political landscape. Against this backdrop, I’ve observed several new trends beginning to take shape. Below, find my advice for keeping up with the changing art world in 2025.

1. Look Beyond Labels

Knowledge of an artist’s education, stylistic associations, gender, race, and sexuality are obviously key to understanding how and why a work was created, and what it means. But these should not be the sole qualifiers for whether a work is worth collecting. Artists from all walks of life need to be represented in our collections and cultural institutions—but when deciding what to buy, look for quality and a clear message, not just the categories that particular artist may or may not fit into. Anyone can be an artist, but not everyone can be a great artist. Look for work that is of its time, pushes boundaries, and has something to say about the world.

2. Revisit Undervalued Artists with Major Influence

Over the past year, I’ve spent a lot of time talking with young artists. I often ask them who their inspirations and key references are for their own work. Besides some Evening Sale household names, the artists I hear mentioned a lot are Mike Kelley, James Rosenquist, Frank Stella, David Wojnarowicz, Richard Prince, and Cindy Sherman. Some of these artists’ prices are at 20-year lows—and some of their work is now cheaper than that of a 20-something who signed with a mega-gallery right out of art school. If you are looking for value, I would also consider American painters from the late 19th century to the mid-20th century, such as Albert Bierstadt, Norman Rockwell, Thomas Hart Benton, and Jared French. These artists are historically important, their work is wonderful to live with, yet their legacies are dwarfed by the hype of the contemporary art market. Smart collectors should consider looking back at some of these artists, especially those that would foster cross-generational dialogue with works already in their collection.

3. Note Disciples of Doig

Peter Doig is a distinguished contemporary artist whose evocative, dreamlike paintings combining figuration and abstraction have commanded prices of more than $25 million on the secondary market. These days, I’m seeing a growing trend in emerging art that I might call the post-Doig aesthetic. Artists working in this style have garnered quick interest from collectors and speculators alike, leading to a rapid rise in secondary market prices for their work. Some, like Florian Krewer, are former students or assistants of Doig. Others following in his footsteps include Justin Caguiat, Arisa Yoshioka, Casey Bolding, and Sedrick Chisom.

4. Remember It’s Not Just Size That Matters—It’s How They Use It

Not to sound like the late, great Dr. Ruth, but bigger is not always better. In fact, I have recently noticed more people gravitating toward artists who work on a smaller scale. Small pieces are easier to live with and more manageable to ship, store, and install. Now, that doesn’t mean you should go out and grab the smallest painting an artist makes. Instead, look for artists that do a decent amount of work in smaller formats. Think Elizabeth Peyton, Paul P., or Andrew Cranston.

Wall space can be a precious thing, especially with people downsizing and living in small spaces. I am all for buying a masterpiece of Guernica proportions, but you need to be sure it’s just that: a masterpiece. There’s a saying amongst artists that goes something like, ‘If you can't make it good, make it big.’ I always advise collectors not to fall into the trap of “trophy hunting,” where the focus is on chasing the biggest, rather than the best, work in a given exhibition. Especially with emerging artists, their careers are way too young for any of us to predict what a masterpiece by them is.

5. Take a Closer Look at Indigenous Art

I’ve observed increasing representation and interest in Indigenous artists in major public and private collections. This is a much-needed correction that taps into an extremely fertile vein in American art history, one that has long been overlooked. That being said, when the market as a whole takes interest in something that can easily be categorized, it’s important to go back to my first point—don’t buy a work just because the artist fits into a particular label. Look for new and older artists who push the envelope and the visual language of their shared experience.

6. Redefine What Is Considered Art

In 2025, the art market is likely to expand its definition of what an artwork is and what can be traded as such. We have all seen thousands of headlines about the $6 million dollar banana, so I won’t bore you with that again. What I am talking about are “collectibles”—items outside what most call the conventional art world, often related to popular culture, yet commanding Evening Sale prices. Top ones to note would be the $32.5 million pair of Dorothy’s ruby slippers from the Wizard of Oz, the $6 million Action Comics No. 1 (a comic featuring the first appearance of Superman), the $1.4 million replica of the Iron Throne from Game of Thrones, and—lest we forget—the Stegosaurus skeleton that became the most valuable fossil ever sold at auction when it fetched $44.6 million last year. For many collectors, part of what makes something art is the way you value and display it. Increasingly, the line between pop culture, great objects, and fine art is becoming blurred.

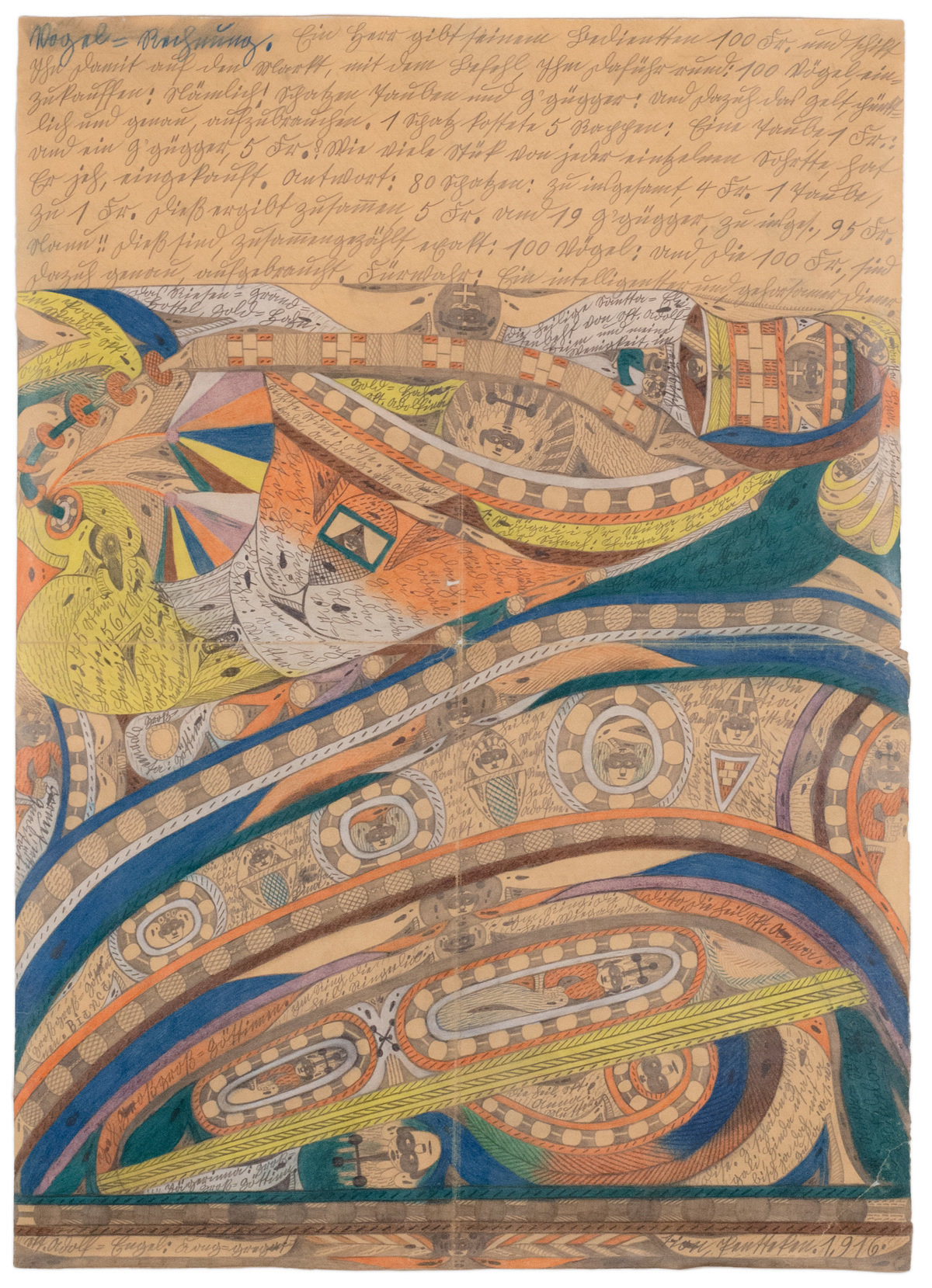

7. Embrace Self-Taught and Outsider Artists

The art market is always on the lookout for new markets to tap, and I’ve witnessed a growing interest in the work of self-taught artists and those who didn’t follow a traditional art school path. This is an area I have collected and loved for years. The entire idea of “outsider” art—categorizing artists based on their education level and/or involvement with the “sophisticated” art world—should seem very silly as we enter 2025. I first really saw the distinction between “mainstream” and “outsider” begin to fade when the gallery David Zwirner held a fantastic Bill Traylor show in Chelsea at the end of 2019. Zwirner has since handled works by self-taught giants like Martín Ramírez, Jon Serl, James Castle, and Adolf Wölfli. Hauser & Wirth has also been mining this field, taking on the estate of Winfred Rembert and hosting a solo exhibition of Thornton Dial this fall.

Critics Jerry Saltz and Roberta Smith often write about self-taught artists and the unique ways they contribute to today’s contemporary art scene. I also highly recommend checking out KAWS’s personal collection of works on paper at the Drawing Center in New York. It’s a great chance to see how “outsider” art stands alongside what we typically consider part of the mainstream art world. The real takeaway here? IT’S ALL ART.

DeLuca’s Definitions: An Art-World Glossary

Art

Art covers a wide range of creative endeavors, typically aiming to evoke an emotional response or convey ideas, beauty, or skill. There's no single definition of what counts as art, and its meaning has changed over time and across cultures.

Cross-generational Dialogue

The interaction or connection between works of art from different time periods, where older works inform, challenge, or complement contemporary pieces.

Evening Sales

High-profile auctions that typically take place in the evening and feature the most expensive works of art on offer.

Mega-Gallery

A large gallery with multiple locations, international recognition, and significant financial resources and market influence, such as David Zwirner, Gagosian, or Hauser & Wirth.

Stylistic Associations

The artistic style or movement with which an artist is associated (e.g., Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art). It involves understanding the influences that shape an artist's visual language or approach.

Trophy Hunting

In the context of collecting, this refers to the tendency to focus on acquiring high-profile works (often the largest or most expensive pieces from an exhibition) without considering the intrinsic artistic value.

in your life?

in your life?