This is Street Smarts, a new column from art advisor Ralph DeLuca that offers art world veterans and newcomers alike a straight-talking, no-bullshit guide to the aloof and difficult-to-crack contemporary art market.

This is my first time writing an article. I’ve been interviewed countless times, but I’m not a writer by any stretch of the imagination. Still, when Sarah Harrelson called me to do this, I yielded to her publishing wisdom, being such a fan of CULTURED (and the amazing profile they did of me last May).

As an art advisor to high-profile collectors in the business and entertainment worlds, I am known for candid straight-talk. I have absolutely zero tolerance for bullshit—and people either love or hate me for it. But I think the tide is in my favor; otherwise, I wouldn’t have the clients and access I do in the art world. I plan to use this column to speak to you exactly the way I speak to my clients as I help them navigate this purposefully difficult and opaque industry. (I’ve even included a handy glossary below to translate art-world lingo into language anyone can understand.)

As my mentor and best friend, Todd Levin, always says, “The educational modality is the largest part of a great art advisor’s job.” You might think my job as an advisor is to encourage clients to buy as much as possible. Honestly, my job is to say no far more than I say yes. I always urge you to trust your eyes and brain more than your ears. These days, the moment you mention an interest in art, people will descend on you like locusts from the Old Testament—especially if they think you have money—to tell you which artist you have to buy right now and which high-profile collectors are scooping up works by the same artists, giving you an almost incurable case of FOMO. That’s where I come in—to offer you the insights you need, help you enjoy the process, and make sure you avoid costly mistakes. (That said—and I’m winking as I write this—this column is in no way a substitute for a great art advisor).

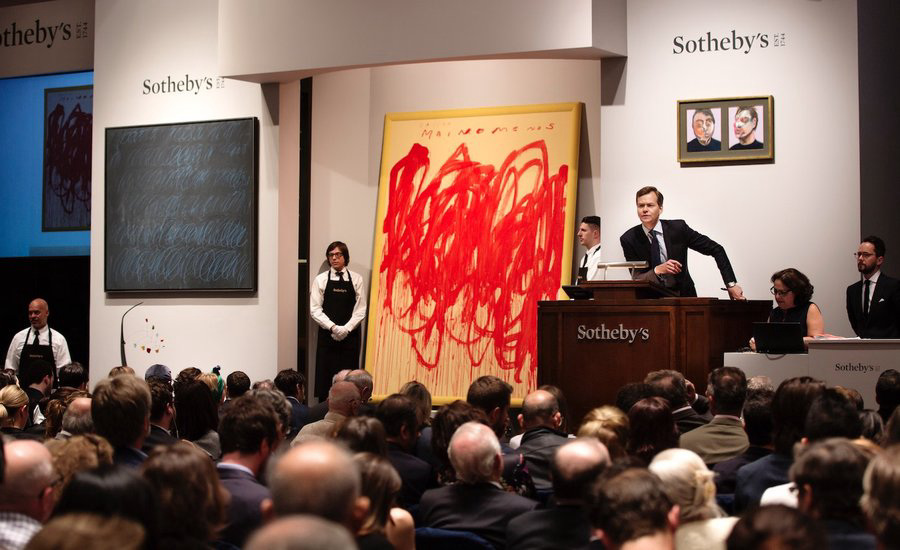

Now, when it comes to emerging art, auctions can be a dangerous playground for the uninformed collector. For reasons I’ll get into, they’re not my preferred way to buy. But if you’re planning to participate in the marquee New York fall auctions this week, here are the five pieces of advice I’d give any collector who wants to come out the other side without any regrets.

1. Understand primary market prices.

Many buyers mistakenly think they’re getting a good deal at auction by comparing the price they paid with previous auction results. They may not realize that the seller purchased the work from the artist’s gallery for $10,000 and is actually making a significant profit. That’s why it’s important for buyers to understand both the artist’s current primary market price and the original primary market price of the work up for auction at the time it was created.

Another thing to bear in mind when purchasing at auction is that the hammer price—the number that flashes on the screen when the auctioneer brings down the gavel—is only part of the equation. There are also buyer’s premiums, which can add between 20 and 30 percent to the hammer price, not to mention shipping costs.

Depending on the location of the auction house, a buyer may also be responsible for paying artist resale royalties and VAT fees. Especially if you have a strict budget for a particular piece, get a sense of the total cost—including having the piece delivered—before you decide to raise your paddle. If you’re buying a sculpture from Christie’s in London and having it shipped to New York, is it truly the score you think it is?

2. Do your research.

Far too often, people rush into auctions without conducting the thorough research they’d apply to any other asset class. It’s essential to understand the full history of an artist’s body of work before making a purchase. Look at the artist’s catalogues, images from previous exhibitions, museum acquisitions, and auction results (if any). Get a feel for the body of work an artist is best known for, which is often a key factor in determining desirability and value.

A lot of advisors will tell you to request a condition report before bidding. I go a step further, especially with older works. The auction houses’ condition reports will always tell you the work is good—otherwise, they wouldn’t be offering it. To get a real understanding of what kind of shape a work is in, you want to ask an auction house point-blank if any restoration has been done to it. And keep in mind, no amount of reading condition reports can substitute for viewing works of art in person whenever possible.

3. Check with the artist's dealer before bidding.

Building relationships with an artist’s gallery is always a good idea. If you want to start collecting art, these are relationships you should be cultivating anyway. Ask the gallery whether they have any new works available or upcoming exhibitions featuring the artist you’re interested in; gauge the demand and accessibility of their work, including whether there is a wait list. Not only can the gallery provide insight into the current primary market price for works of similar size and type (really—just ask them!), they may also guide you to other available examples on the private market. (They may even know a collector holding on to just the kind of work you want who is open to selling, but hasn’t pulled the trigger.) Even if you're after a specific series that the artist no longer creates, know that auctions aren’t your only option.

4. Don't believe everything you read.

It’s very easy to get swept up in doomscrolling negative articles about the slumping art market. But things aren’t always as dire as they seem. It’s important to dig deeper, understand the context, and not let sensational headlines dictate your actions.

Allow me to refer back to point number one. People see secondary prices go down and think the artist’s market is in freefall when their work may still be selling far above the primary price it was originally purchased for.

5. Make sure you've thought through your options.

I rarely advocate for clients—myself included—to purchase emerging art at auction or on the secondary market, with very few exceptions. Young artists, in particular, are often treated like stocks, with some people believing their work can be rapidly traded like commodities. In most cases, this approach is a fool’s game that can lead to buyer’s remorse, strained relationships, lost access to primary works, and entanglements with less reputable art world “flippers.”

Access to sought-after work from a brand new exhibition or in between shows is often difficult for new clients to obtain, which is why I always encourage checking with an artist’s primary market dealers to see what’s available on the secondary market instead. If it makes financial sense and you’re eager to own the artist’s work, a secondary market purchase through the artist’s primary dealer can be an excellent way to begin building a relationship with their gallery.

To anyone considering participating in this auction season, I am wishing you luck. Just do your research first, as the informed buyer can bid to win.

DeLuca’s Definitions: An Art-World Glossary

Primary market

The primary art market refers to the original sale of an artwork, either through a gallery or directly from the artist’s studio. In the primary market, prices are set by the artists and the galleries that represent them, typically based on the artwork’s size and medium. The primary price for a particular work should remain consistent across all galleries representing that artist. Primary access typically refers to exclusive opportunities to acquire an artist’s latest works by their represented gallery, often before they reach the broader market. In the competitive contemporary art world, this kind of access is especially valuable.

Secondary market

The secondary market involves the resale of artworks—in other words, the sale of works that were previously purchased on the primary market. Unlike primary sales, which typically occur through galleries or directly from artists, secondary market transactions take place through auction houses or private sales usually brokered by dealers. (I'll get into the daisy-chain that can come from those private sales another time!)

Flipper

Someone who buys a work of art and quickly sells it to try and make a profit (usually without the consent of the artist’s gallery or galleries), with little regard for the harm it might do to the artist long-term.

in your life?

in your life?