For the Big Picture this week, the Critics’ Table enters the fray, taking a close look at Dean Kissick's recent, polarizing cover article for Harper’s. Our guest critic, the artist Ajay Kurian, questions Kissick’s assumptions about marginalized identities and major institutional exhibitions, suggesting that—as art discourse dovetails with anti-woke culture wars and we descend deeper into hell—neither DEI window dressing nor a return to the past will save us.

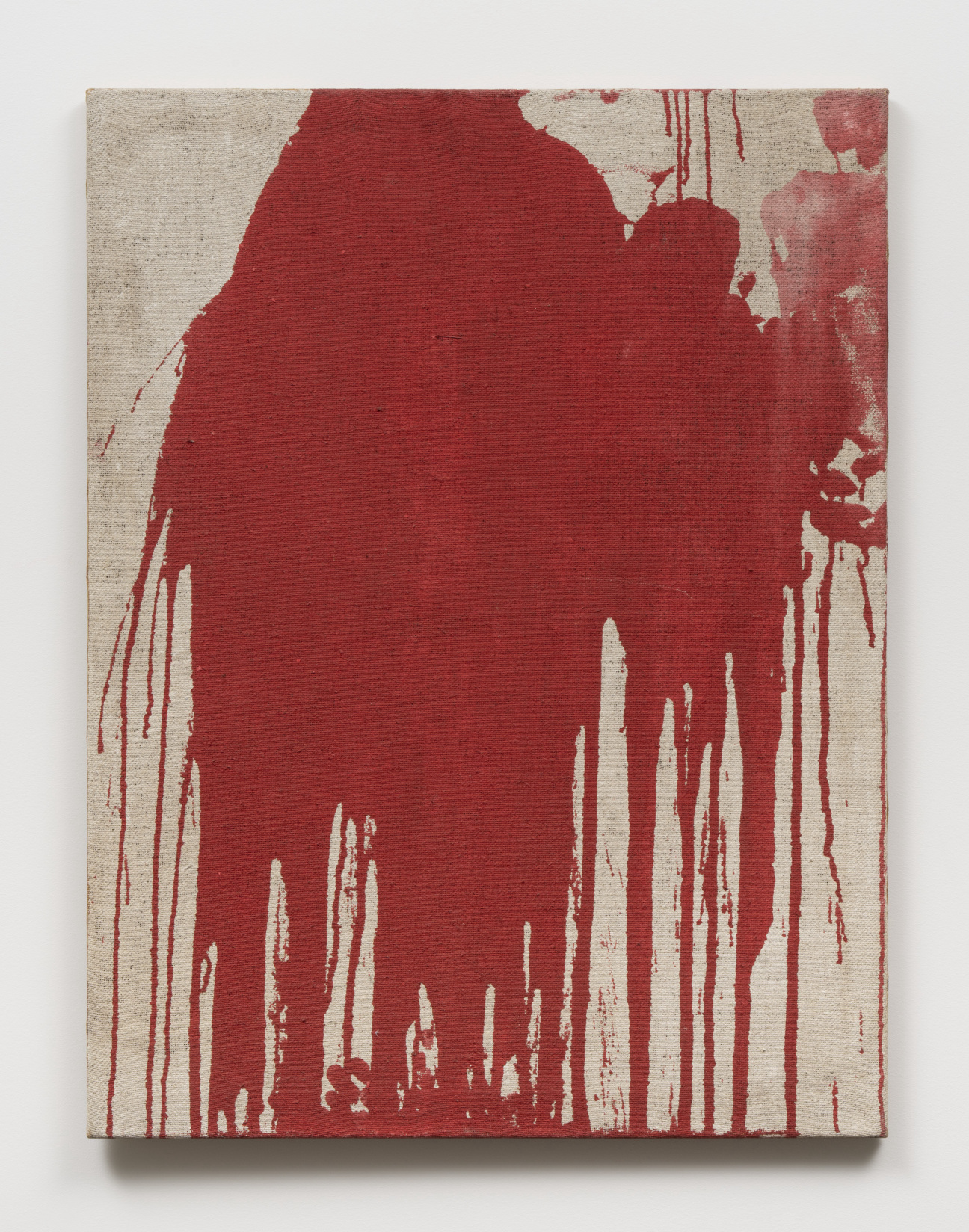

It was as a student at a Christian boy’s school in Oxford, England, that the critic Dean Kissick was first exposed to the work of Viennese Actionist Hermann Nitsch. Kissick fondly recalls the documentation of one of Nitsch’s Das Orgien Mysterien Theater (Theater of Orgies and Mystery) performances, describing naked participants in the Austrian countryside “wrapped in white sheets, soaked in the blood of cows they had sacrificed, performing rituals in their commune.” This is how, he explains, he came to understand Modernist transgression. Nitsch’s productions “had nothing to do with personal identity or the imparting of information,” Kissick insists. “They were, rather, attempts to leave social norms and Apollonian rationality behind and to embrace Dionysian chaos.”

As if to transgress conventional art writing decorum, Kissick begins his Harper’s debut, “The Painted Protest: How politics destroyed contemporary art” (the 174-year-old magazine’s December cover story) with an unsettling personal tragedy, telling readers of the day his mother lost both her legs. She was run over by a bus while on her way to the Barbican Art Gallery, where she had planned to see “Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art”—the exhibition that serves as Kissick’s first case study on the precipitous decline of contemporary art in the past decade.

To transgress in order to shock is a manipulative affair. To use it to write off a generalized category of artists and art-making is, for Kissick, very on brand.

The meandering text, with its scattershot construction, ill-defined terms, and succession of straw-man arguments, is difficult to summarize briefly, but at the heart of it lies Kissick’s resentment for art “about identity,” its perceived claims to social transformation, and the increased attention given to artists of marginalized backgrounds. It seems written from the perspective of someone who has endured the arrows of woke puritanism for too long and has the bravery to declare enough is enough.

Kissick recalls his heady days in the summer of 2008, when he scored an internship with the super-curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, and the convening of Kissick’s friends on an airport floor in the afterglow of the 2013 Venice Biennale, when contemporary art was still defined by “the ambition to explore every facet of the present.” After around 2016, though, he begins to detect “a new answer to the question of what art should do: it should amplify the voices of the historically marginalized. What it shouldn’t do it seems,” he sighs, “is be inventive or interesting.”

He provides many examples of what he deems staid and backward-looking for their engagement with traditional techniques—from Jeffrey Gibson’s large-scale beaded works inspired by his Chocktaw-Cherokee heritage to Louis Fratino’s rendering of his queer world in the styles of European and American Modernist painters. It is not these latter practices that Kissick particularly tends to consign to the past, though; it's those from non-Western and Indigenous cultures.

His reactionary musings would have, under other conditions, hardly raised an eyebrow—if, for example, he posted his critique as a series of glib tweets, or in his column "The Downward Spiral," which he wrote for the Berlin- and Vienna-based Spike Art Magazine from 2017 to 2022. (Kissick is an aging art-world edgelord of sorts; he has long posed as a jokey tell-it-like-it-is corrective to kill-joy social-justice types, taunting though never seriously engaging his detractors.) But the appearance of his nearly 7,000-word-long text in a legacy magazine whose readers know little about the biennial circuit of which he writes, and even less about the art world’s shifting fault lines and demographics over the past three decades or so—just weeks after the U.S. presidential election—has lit up the group chats, so to speak.

The rightward drift exposed by the public applause for Kissick’s piece can’t be viewed separately from its larger culture-war context. It’s Ron DeSantis’s world now: Even Democrats blame their epic losses on, of all things, the defense of trans rights. Following book-banning campaigns and attacks on “critical race theory”—which has been cast by Republicans as a conspiracy to make white children feel ashamed—Trump has promised his aggrieved supporters that he will punish schools and institutions he sees as "too woke."

It’s an old story. Backlash has followed each moment of Black social gain, from the post-Civil War era to the election of Barack Obama. An oft-repeated question from the “post-racial” Obama years was something to the effect of: How can racism exist when a Black man holds the highest office in the land?

Kissick, for his part, asks: “When the world’s most influential, best-funded exhibitions are dedicated to amplifying marginalized voices, are those voices still marginalized?” According to his logic, the existence of such exhibitions proves their existence is not needed; marginalized artists now “speak for the cultural mainstream, backed by institutional authority. The project of centering the previously excluded has been completed.” Out of context, the statement might read as satire—it’s not.

If a handful of exhibitions were enough to center the previously excluded, I imagine we would have seen at least a subtle shift in the art world’s commitments after the notorious Whitney Biennial of 1993 (the then unprecedentedly diverse, so-called “identity politics” biennial). In fact, it’s taken decades for the composition of major institutional endeavors to change meaningfully, and for reasonable conversations about such problems to erupt and gain a foothold in mainstream art discourse—that is, conversations about the histories of violence that divide experiences of the body according to race, and shape both “identity” and the way that term is wielded. (For reference, the Whitney Biennial of 2014, the last that falls within the timespan of Kissick’s glory days, was notable for its dismal stats. Thirty-two percent of its artists were women; nine out of 118 were Black—and one of those was actually a fictional Black woman character created by a white man, Joe Scanlan.)

Michael Kimmelman, painting the ’93 biennial with too big a brush (he was then the chief art critic for The New York Times), wrote flatly that he hated it, lambasting the obviousness, the simplicity, and the browbeating on view. One artwork he prominently took to task was that of Daniel Joseph Martinez’s metal tags, distributed at the museum’s entrance, that read, “I CAN’T IMAGINE EVER WANTING TO BE WHITE.” “As if a Neanderthal would change his mind after being forced, like a penitent, to don one of the infamous admission badges,” Kimmelman sputtered, “and then being bullied and harangued by one sensationalistic image after another of wounded bodies, heaving buttocks, plastic vomit and genitalia.” (This was his characterization of an exhibition featuring artists such as Mike Kelley, Lorna Simpson, Robert Gober, Renée Green, and Julie Dash.)

Cut to Kissick calling the exhibition at the Barbican the most depressing he’s ever visited at the gallery. His bland narration of the show—the one his mother tragically did not get to see—sets the tone for his approach to artworks in general. Terse descriptions gesture towards a neutral representation of what’s on view. The ridiculousness and impotence of the textile-based works—and their connection to gendered labor and non-Western craft traditions—is, thus, self-evident. His recitation of included works and weary descriptions of the artists’ ineffectual protests following the Barbican’s cancelation of an event, which was to feature a talk critical of Zionism, are dismissive in the extreme. But they culminate in a conclusion that merits closer unpacking. “While ‘Unravel’ pretended to be politically radical—even revolutionary,” Kissick writes, “it didn’t seem to stand for much beyond liberal orthodoxy and feel-good ambient diversity.”

Read generously, Kissick almost seems to sympathize with a radical critique of institutions—the observation that curators and administrators routinely instrumentalize marginalized artists to obscure enduring structural inequities or exonerate their museums and galleries of past crimes—but he makes no clear distinction between DEI window dressing and the work itself.

The art world is flush with mediocre and safe work. It always is. The answer, though, isn’t to return to 2014—or 1993. The impulse to look to some past standard of artistic excellence in order to battle mediocrity only seems to arise when artists of color are in question. I can’t recall a moment when critics took to their soapboxes to lament the trend of bad white art.

One need not love this year’s Whitney Biennial to see that Kissick’s critique of it is conducted in bad faith. Nowhere is this more obvious than in his conflation of wall labels and artworks. Reading the accompanying text for Dora Budor’s experimental film, Lifelike, 2024, which is composed of vibrating footage of the Hudson Yards real estate development (the artist attached a “vibrating pleasure device” to her camera), Kissick throws his hands up, unable to see how the piece “interrelates industrial production, the privatization of pleasure, and the mechanics of biopolitical control.” Measuring the political and aesthetic efficacy of an artwork is a fool’s errand; measuring it against curatorial claims or third-party theorizations of it is critically bankrupt. Surely we could choose from the handful of works Kissick lauds—those plucked from his imagined Golden Age of contemporary art—and subject them to the same torture with similar results.

When Kimmelman described Martinez’s work, he assumed the piece was meant to change the minds of white people. But the badges weren’t for them in the first place. There was (and still is) another audience who has historically been ignored by institutions—Martinez made a participatory, conceptual work for people of color. When whiteness is actively decentered, critics predictably malfunction. Likewise, when Kissick describes the 2024 Venice Biennale, cheekily titled “Foreigners Everywhere,” his main complaint is that, as he writes, “in a world with Foreigners Everywhere, differences have flattened and all forms of oppression have blended into one universal grief.” An excess of diversity becomes, in a neat trick, a new form of homogeneity. “We are bombarded with identities until they become meaningless,” Kissick continues. “When everyone’s tossed together into the big salad of marginalization, otherness is made banal and abstract.” The assertion raises the preposterous question: Without enough whiteness as a backdrop, do other identities even exist? Who is the “we” here being bombarded with identities if not a dominant, white audience—those universal subjects excluded from Kissick’s salad?

The critique is exhaustingly familiar. Hysteria over the loss of the canon still plagues universities, but the panic began much earlier. From the ’60s onward, politicians and strategists have sounded the alarm over the contestation of “traditional” values on campuses, warning that it threatens to reach the larger population. Enter the ’80s term "political correctness." Here was a label conservative thinkers could weaponize against their invented left-wing “thought police.” Today, politicians call it “woke.” Art critics and leftist poseurs call it “identity politics.” Its purpose, whether conscious or not, remains consistent. It casts those who agitate for social change as the real conservatives—censorial, prudish, doctrinaire. And those who uphold anti-woke orthodoxies are the rebels.

We see that Great Art needs a good old-fashioned universal subject paired with an air of rebellion—such as in the oeuvre of Nitsch. His work, as Kissick puts it, "had nothing to do with personal identity." But let’s pause for a moment. Nitsch was born in Vienna in 1938, the year of Austria’s annexation by Hitler; and lived as a young child in the city through more than 50 Allied bombing raids during World War II. His father died in Russia, fighting for Germany, which Nitsch said had a profound impact on him. I would argue that his art is laden with identity. It’s a European, generational identity, formed by—among other things—trauma and guilt. His art derives from the innovations of his German predecessors. Nitsch worked in the 19th-century traditions of Wagner’s Gesamtkunstwerk and drew upon Nietzsche’s aesthetic theory.

There is an identitarian absolution granted to white artists that is rarely extended to artists of color. If I were to make a performance that drew from Indian history and related it to Bharata Muni’s ancient text on theater, it would go without saying that I was producing identity-based work in Kissick’s view—even if my performance didn’t begin or end with those cultural references. Nitsch, and so many other white artists, somehow pass through the gauntlet of identity untouched. Free from context, from history, from “difference,” their art is boundless in meaning. Such a reading of Nitsch's transgressive work—of anyone’s work—is like pushing away the food on the table to eat from your ass instead.

Ajay Kurian is an artist, writer, and educator. He is represented by 47 Canal in New York and Sies+Höke in Düsseldorf, Germany. He also runs the educational company, NewCrits which offers virtual studio mentorship for artists. He recently had a show at Von Ammon Co in Washington DC.