Few contemporary artists have captured the imagination of the art world like Lauren Halsey. Not yet 40, the artist has shown in the most august of spaces, including the roof of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Venice Biennale. But her distinct visual language and expansive creative practice are fuelled by, and rooted in, her home in South Central Los Angeles. For her first U.K. exhibition, “emajendat,” on view through March 2, 2025, Halsey transformed the Serpentine in London’s Kensington Gardens into an immersive “Funk garden” that extends into the galleries.

The artist’s first major monograph will be released in coordination with the exhibition. For that volume, Halsey sat down with Lizzie Carey-Thomas, the Serpentine’s director of programme, and the Serpentine’s artistic director, Hans Ulrich Obrist, to discuss her journey to the exhibition and how it fuels even bigger projects she is developing back home. What follows is an edited excerpt of their conversation.

Hans Ulrich Obrist: Lauren, let’s start at the beginning. You initially went to architecture school and for you, art and architecture are connected. So how did it all begin with architecture?

Lauren Halsey: I grew up in South Central Los Angeles. However, I went to school outside of these neighborhoods. I was able to be both an insider and an outsider every day, unknowingly as a child. In a place where car culture is pretty much everything, I, at an early age, noticed nuances in architectural materiality. For example, the material differences on the exteriors of neighborhoods in South Central, versus the exterior of a city block in Westchester—neighborhoods, geographically speaking, that are right next door to one another—differences such as businesses with bars on windows or bulletproof Plexiglas inside versus neighborhoods where this isn’t the case. This materiality shapes how I perceive myself and how I perceive others. I would often wonder, Who made that material choice to do this? To communicate that I’m dangerous, that my community is dangerous, that we’re a threat, and we need to be oppressed and controlled?

In high school I was a very quiet kid, much more than I am now. At church there were plays that I didn’t want to perform or recite lines in, so my aunt would ask, "Would you rather build the set?" As a middle-schooler I ended up spending a lot of time in my backyard using my father’s recycled building materials and my mother’s craft materials to create church sets.

So, fast forward, I graduate from high school, I’m in community college and I’m taking the basics, the prerequisites that you need to transfer. Yet I don’t have a clear sense of direction. Around the same time, this same aunt introduces me to the artist Dominique Moody and she asks me, "What do you want to do?" I told her, "I love building sets." She responds, "Well, have you thought about building architecture?" I took an architecture class and I immediately understood the power of space-making, specifically creating a set of blueprints to propose tangible spaces at a very high level. I had no idea back then what it meant to get something built.

I was in community college for four or five years, riding the same bus route: up and down Western Avenue, Broadway, across Crenshaw Boulevard. I’m paying even closer attention to the city now, because I’m enrolled in the architecture program. And I’m documenting the specifics of the city, content for what I describe as fantastical spatial proposals. I’m counting the barbed-wire fences. I’m going into the stores and trying to make sense of why buying and selling orange juice and candy requires all this security and bulletproof glass. In the process, I determined that perhaps I won’t become an architect. What if I used art to communicate alternative messaging to the store owner, most especially concerning their perception of Black and Brown people? And, bigger than that, how could I use art to explore and honor the different ways these Black and Brown communities imagine and experience our neighborhoods, lived histories and physical environments?

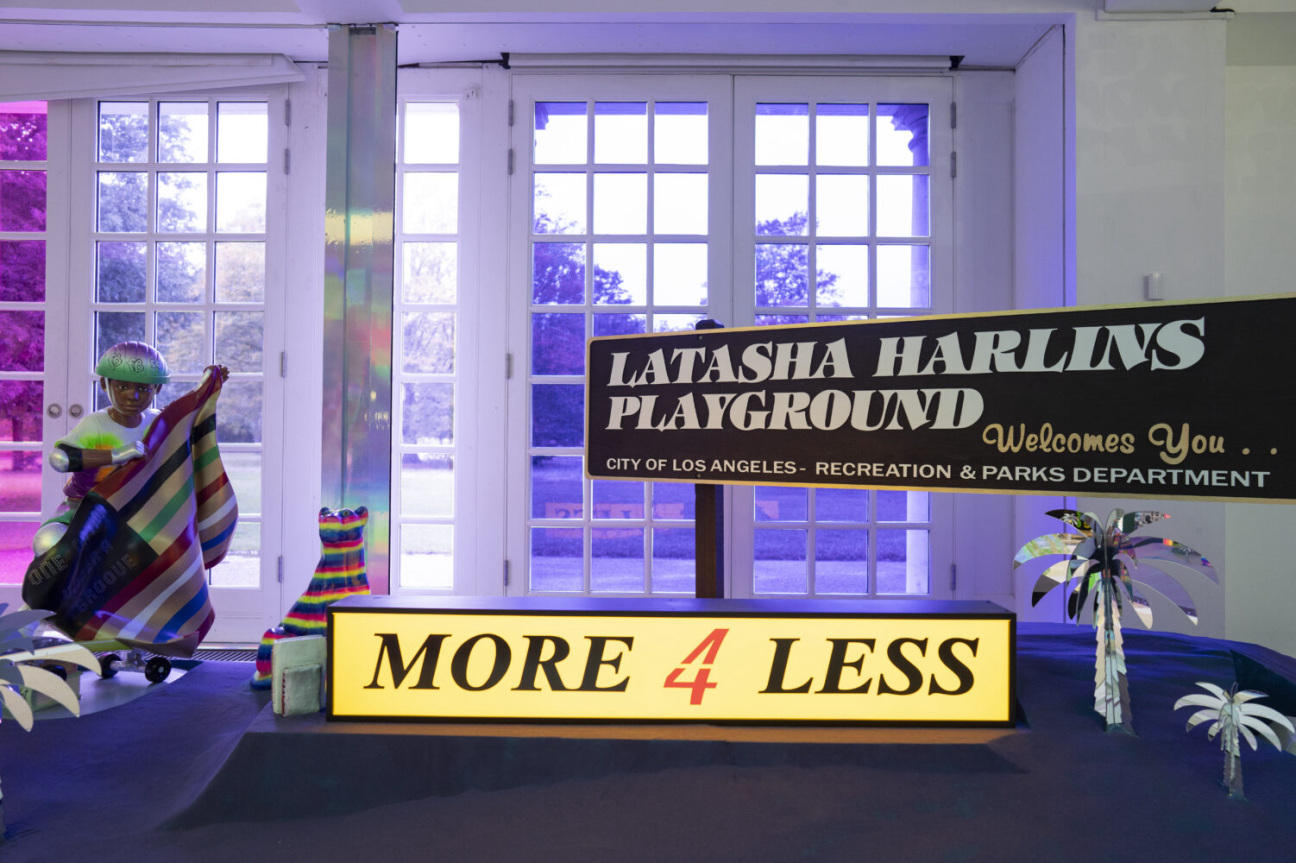

I was basically dreaming up the project that I’m working on now [sister dreamer, lauren halsey’s architectural ode to tha surge n splurge of south central los angeles]. At the same time I was building a garden in my grandmother’s backyard with my best friend (who still works with me) and my little cousins. In LA, everyone, for the most part, has a backyard with some sort of garden that they’re tending to. I thought, How cool could it be to make a garden to sit in and ponder and harvest but, also, make hyperaesthetic and psychedelic? A garden that looks like us, that feels like us, that’s aspirational, dreamy, technicolor and funky. The Serpentine show is the next iteration of this. It’s a study for a series of funk garden projects that I envision building in South Central LA, the culminating one being a permanent garden at Jesse Owens Park.

Lizzie Carey-Thomas: You’ve commented that the project sister dreamer in your neighborhood took 17 years to realize, and that everything, in a way, has been leading up to that point. Every project you’ve done along the way has been a prototype. Did you always have this neighborhood project as your goal?

Halsey: When I was in community college pursuing architecture, LA wasn’t being hyper-developed at the rate it is now. For a stretch of about seven or eight miles, up and down my favorite avenues, there were numerous vacant lots that I could project fantasies onto. A lot of the collages and maps I made over a decade ago focused on remixing a certain corner or a specific intersection I would obsess over. Sister dreamer is the first architecture of many that I’ll present in the neighborhood. It’s pretty incredible that the former plot was an ice cream shop, a landmark in its own right that we went to as kids.

Carey-Thomas: I want to ask you about your experience of moving through the city. You talked about the car culture of South Central LA and the way you traversed the city on the bus, traveling between home and college. I know that’s something you still do today, taking photographs and collecting material. What inspired you to start documenting the changing streetscape?

Halsey: I’m just so attracted to the neighborhood—especially our material culture. I’m not saying it’s just a South Central thing. You can go to Harlem, as well as places throughout the African diaspora, and sense a similar language and vernacular around material, objects, density, color. Because I’m from Los Angeles, I take pride in its specific manifestations of this cultural dynamic. To understand and frame these neighborhoods in this way, however, competes against the dominant representations or narrative of these communities as raggedy, suppressed, poor or of a lower cultural status. My work explores and celebrates an alternative narrative: a narrative of South Central LA where you’re existing amongst a palette that’s energetic, inviting, and beautiful, where you go inside a shop and people are making and selling these fantastic objects. That’s also a reality experienced by these communities, but it’s not always depicted in media or art. We’re far more than the problematic narratives and conditions that have been placed upon us and which we have to endure.

Ulrich Obrist: That’s beautiful. The first time I saw your work was in 2018 at MOCA, which was a revelation. I went to see it with Bettina Korek [CEO, Serpentine] and we were absolutely struck by we still here, there, because a lot of your visual language was already there. What you’re doing now for Serpentine is, of course, different because your language has evolved, but much of it was already there in this early work: the layers, the density.

Halsey: We made that work in my grandmother’s backyard. For the show at Serpentine, I’ve been collecting a series of animals for a long time that I buy from people off the street. All of them function in domestic spaces, as piggy banks, or actual furniture. For the show I’m going to populate the "garden" with my remix of those animals.

Ulrich Obrist: At MOCA you made a composition of the neighborhood, of parties. It was also sort of sampling and archiving ephemera, voices, and stories. In a way, it’s a form of maximalism. You brought all these elements together for the first time. Visitors were greeted at the entrance by a mannequin that held a Pan-African map, which also, I think, was a connection to the artist David Hammons. I remember in our first conversation, you mentioned that the residency at the Studio Museum in Harlem was really important in the build-up to that.

Halsey: Yes and no. Essentially, with the budget we had, it was a project that functioned as a study for what’s to come and you’re right, the language had to evolve. It was supposed to be a cavernous room with interior spaces that you move through; the idea being that these spaces held our archives. It was supposed to function as a riff on the cave. You know, the cave being a storehouse for one’s culture—a site where we display artifacts, bask in them, light them, and take them seriously. We included everything from Kankekalon hair and figurines to protest signage, advertisements, and miniature architectures of my favorite mom-n-pop shops. Then there were water features. What was so special about that was that I built it with people I love and have a deep history with. So, rather than act as an architect who designs projects but has someone else build them, I was able to collaboratively build in my grandmother’s backyard with, literally, everybody. My family, my friends, people like my little cousins and their home girls, who were 7 or 8 years old at the time. What this meant was that my community was able to take ownership and author the forms of this spatial imaginary.

Carey-Thomas: And that sense of involving your friends and family has continued. The collaborative aspect of what you do is reflected in the work itself, whether you’re actually making representations of those people that are important in your life or convening a space for them.

Halsey: Yes, the process has, at times, been hard, most especially because things have become so formal. Now I can’t just make something in the backyard where my aunt comes by after work and puts her hand in it and someone cuts on the grills and rolls up a blunt. We now have deadlines and my studio can’t accommodate this freedom of being anymore. But I’m really excited about the architecture and creative projects that’ll open [in South Central LA] next May and the programming that will occur in tandem with the projects. The art and programming will be tethered to those folks and micro-communities that I really love.

Ulrich Obrist: Can you talk more about funk? I was listening to an interview with Lanka Tattersall, which you gave during the MOCA show, and you talk about Parliament-Funkadelic and George Clinton. When I interviewed Clinton in the late '90s at his hotel room in Paris, he welcomed me by saying, "I am Funkenstein." We did a long interview where we discussed the idea that funk de-emphasises the aspect of melodic progression and focuses more on a rhythmic bassline groove type of thing. You make an analogy between visual art and music, where you say that you "funkatise" certain aspects.

Halsey: Funk is life. It’s oxygen, water, air. Funk is freedom. It’s my life force. It gives me the conceit and the attitude and the energy to reach my level. To reach the level where everything is "on the One," which is what George and Parliament-Funkadelic subscribe to. Once you reach your ultimate level of your maximum funkmanship, everything is on the One, and you’re doing something right. I’m just in the vacuum of that, as a head-space, and I think that’s my armor—not armor, maybe that’s the wrong word. No, it’s more of that heart space that I live with that gives me the freedom to dream, and see, and transform, and remix, and just be at the level of my ideal funk.

Ulrich Obrist: Yes, you can’t define it, but it definitely combines loads of things. There’s rhythm, there’s blues, there’s soul music.

Halsey: The layering is so brilliant. At one point, George Clinton had 83 people in the band. Talk about maximalism, and sensorial overload! There are people who are the professional, good time hand-clappers, who are there as the "amen" corner. There are the people who are walking around, performing as dignitaries, with the P-Funk flag. There’s the person in the corner talking shit. Each layer adds up to the funk George is trying to summon. I hope that the maximalism I bring to my work is received the same way, where people aren’t overwhelmed, or thinking. This is too much of the too-muchness. I hope they’re intrigued and seduced to want to decode it, sit in it, and be of it.

Carey-Thomas: Do you feel that sensibility was behind the early digital collages that you made?

Halsey: One hundred percent. My collages weren’t set up to communicate traditional conventions of space-making. They were about proposing the impossible with funk and Black maximalism always in mind.

Ulrich Obrist: Can you talk more about the immersion? The Serpentine show will be deeply immersive, through the mirroring of the CDs and through the water. It’s participatory.

Halsey: Yes. There’s a few swap meets that I’ve always enjoyed going to. My favorite booths are the ones where they don’t throw anything away. They just keep their inventory and add, add, add. I always feel nourished in those spaces because I love sitting and peeling back and experiencing their layers. Other folks might call it hoarding. I perceive it as a different style or principle of organization, and I respect that style. I want my work to have the same sort of intensity, where it holds you, and you have to contend with its physicality.

Carey-Thomas: It’s almost like being in a material VR experience, the way you describe it, in that it’s completely around you, and as you move your head, you discover new aspects and perspectives.

Halsey: You’re surrounded, you’re consumed.

Carey-Thomas: You mentioned that your community initiative Summaeverythang was going to devise the public programme for the sister dreamer project (previous and opposite), and obviously this idea of making a space to convene is something that’s super important to you. It would be really interesting to hear about the origins of Summaeverythang.

Halsey: I bought my studio because I wanted to program with the students attending the middle and high school just down the block. Owning and maintaining a studio and building of this nature however is a slow burn—a marathon process—because all of this is very expensive. But Barbara Bestor, who designed the Silverlake Conservatory of Music, is the architect for the project and we have her schematic designs. Now I have to fundraise $2 million to get it built.

Ulrich Obrist: Initially, you did kitchen after-school programs that were led by your girlfriend, Monique, then little by little, during the pandemic, they became bigger. They became these amazing food programs where you basically created a whole supply chain. You once said, "Where folks lack, we pick up the slack."

Halsey: I was listening to Maxine Waters [the long-serving Californian politician] on the radio talking about this false idea that Black people don’t do anything for each other. And I’m just like, I can go to so many community centers and organizations and meet all sorts of folks who are offering and facilitating programmes and services at a very high level right now. The issue is that everyone’s under-resourced. But you better give back. What would it mean to make all this work about my community if I’m not contributing tangibly to its transcendence and upkeep?

Carey-Thomas: I wanted to ask about the way that the works for the Venice Biennale and the Met pose as a monument on the one hand, but also create a dynamic space that’s usable, a space that people contribute to collectively and collaboratively.

Halsey: I think the narratives, the subject, the people, the community, the neighborhood, the art, are as monumental as the work that I hope represents it. So that’s where the scale comes from. The pillars in Venice, for example, paid homage to my personal pantheon of fantastic community figures. People such as Susan Burton, Dr. Rachel Eubanks, my grandmother, who are monuments unto themselves. They don’t get to be on-stage because they’re so busy being in service of others.

Carey-Thomas: There’s a distinct contrast between the intensely coloured materials in your dioramas, and the plasterworks, which repeat many of the same slogans and images, but in a single register. I wondered what drove you, in your more architectural projects, to think about using one material, to not have color?

Halsey: I think sometimes color can be a distraction, depending on who’s looking. And that was my lesson in grad school: that I could have made anything as long as I put some glitter on it and made it holographic and people would be seduced. They didn’t care about the content. So more and more I moved away from that.

Ulrich Obrist: It’s interesting that the Met project has the scale of architecture, but you still say it’s a study. When I asked you about your dream project, you talked about having some land that accumulates a remix of elements of the city. I think that’s crucial because I have the feeling that, at the moment, there’s a desire expressed by artists to go beyond the exhibition. For example, Yinka Shonibare has a farm in Nigeria, Adrián Villar Rojas has a farm in Argentina, and Precious Okoyomon wants to do a garden instead of an exhibition. You actually have the most ambitious project because you want to make your own city. How would this city work?

Halsey: I would just build and I’d invite people to build. I don’t know, there’s freedom in not defining it. I get tired of defining. It’s similar to the way the Watts Towers, 1921–54 came to be. Simon Rodia started building them and people were like, "What the fuck is he doing?" So they reached a certain scale they were like, "Oh my God, this is beautiful. I want to be a part of that, I’m going to leave material by his door." That’s the kind of project and continuum I’m participating in and which I hope my work is in service of.

in your life?

in your life?