Welcome to The Big Picture, where CULTURED’s critics zoom out for a wider view of the art world. While reviews remain the focus of The Critics’ Table, this space is reserved for longer reflections—treatises, prognostications, diaries, and meanderings. Really, anything goes.

The great novelist and art critic Gary Indiana, who passed away last week in his East Village apartment, leaving a hole in the city’s literary firmament the size of his name state, isn’t generally remembered for his favorable reviews. Maybe it’s because even his positive assessments were not positive—not in tone. They emerged from a deep anticapitalist snobbery; his caustic disdain for the commercial structures and depraved characters of the (art) world was justified, implicitly, on aesthetic as much as political grounds. Though in the universe of his writing—by the rules of his bitchy radicalism—no such distinction exists.

Yet Indiana did love many things. I know that from the conversations I was lucky enough to have with him over the years (mostly at parties). And I found or remembered more examples, flipping sadly through Vile Days when I learned of his death. The book, which I keep close at hand, anthologizes the writer’s Village Voice columns from 1985–1988, his years as the paper’s senior art critic. The day before, I had attended the press preview for Nicole Eisenman’s new public sculpture in Madison Square Park, and so, as I was thinking about Indiana—and this collection particularly—I was also mulling over Eisenman’s monumentally-scaled anti-monument, Fixed Crane.

As its title suggests, the work’s main element is a towering piece of construction machinery. It towers no more, though: the artist has felled and gutted a 90-foot-tall, decommissioned Link-Belt crane. The massive thing sprawls on its side across the park’s oval lawn.

I found myself returning to a review of Robert Gober’s 1987 show at Paula Cooper Gallery—rather than, say, Indiana’s writing on public art or on Gordon Matta-Clark—as I considered Eisenman’s momentous outdoor commission. In keeping with the critic’s negative slant, he prefaces his sensitive—and laudatory—reading of Gober’s exhibition with two scathing blind items: one about a collector he heard voice ambivalence concerning the handwrought quality of the artist’s work (démodé in the era of hands-off Post-conceptual sculpture), the other about a cynical powerbroker the critic sarcastically identifies as “one of our gutsiest art consultants.”

With that taken care of, Indiana proceeds to detail Gober’s painstakingly made, defamiliarized domestic objects, such as an X-shaped crib and playpen. He dwells particularly on a pair of nonfunctional porcelain-looking urinal sculptures, made from plaster, wire, wood, and enamel paint, noting that they ineluctably invoke Marcel Duchamp’s seminal gesture of 1917, his factory-fabricated, R. Mutt-signed urinal—the dictionary-definition of the readymade—which made art a game of context and designation over craft and creation. Indiana summarizes, with characteristically louche precision, the key difference between the artists’ works: “The readymade urinal only talks about art, the art system, art values; Gober’s urinals tell you about pissing, standing next to other people pissing, about cocks and having one or not.” Hold that thought.

Eisenman’s recontextualization, or repositioning, of the mammoth machine is a gratifying sight for New Yorkers (or at least for this one) who are chronically rerouted and otherwise plagued by construction projects, and who have come to see the crane as an emblem of an unceasing real-estate development industry—a corrupt Goliath that makes no dent in the housing crisis and steadily worsens the city’s cruel inequalities. The artist’s motives seem only a little vengeful, though. The crane is old and battered; its red paint is chipped; it feels more salvaged than slain. Released from its duty as an erector, it becomes a horizontal display armature for smaller objects, including an assemblage of driftwood and rainbow-hued embroidery thread by Eisenman’s son; a tuna fish can; and a cartoony, overturned chalice. On the idyllic, breezy autumn day of Fixed Crane’s unveiling, the artist tells me that the emptied cup is a way of saying the party’s over. She points up, to the top of a slender metal rod, which rises, perpendicular, from the crane’s treads, musing that the gloopy, hand-modeled figure hanging on to it looks like a white flag of surrender.

The last time we spoke about her sculptural work was five years ago, in her Brooklyn studio, as she prepared to install her multi-figure scene Procession on the Whitney Museum’s sixth-floor terrace, for the occasion of the 2019 Biennial. Made from a curious mélange of materials (bronze, wax, wool), the ragtag caravan of giants and assorted objects—with its absurd Washington-Crossing-the-Delaware configuration and symbolic density—echoed the tragicomic allegories and collisions of style often found in Eisenman’s canvases.

With three decades of figurative painting under her belt, the queer artist approached the rendering of bodies in three-dimensional space with a practiced nuance, lending them a humane indeterminacy. Her introspective, heavy-limbed beings seemed to hail from a time before or beyond gender.

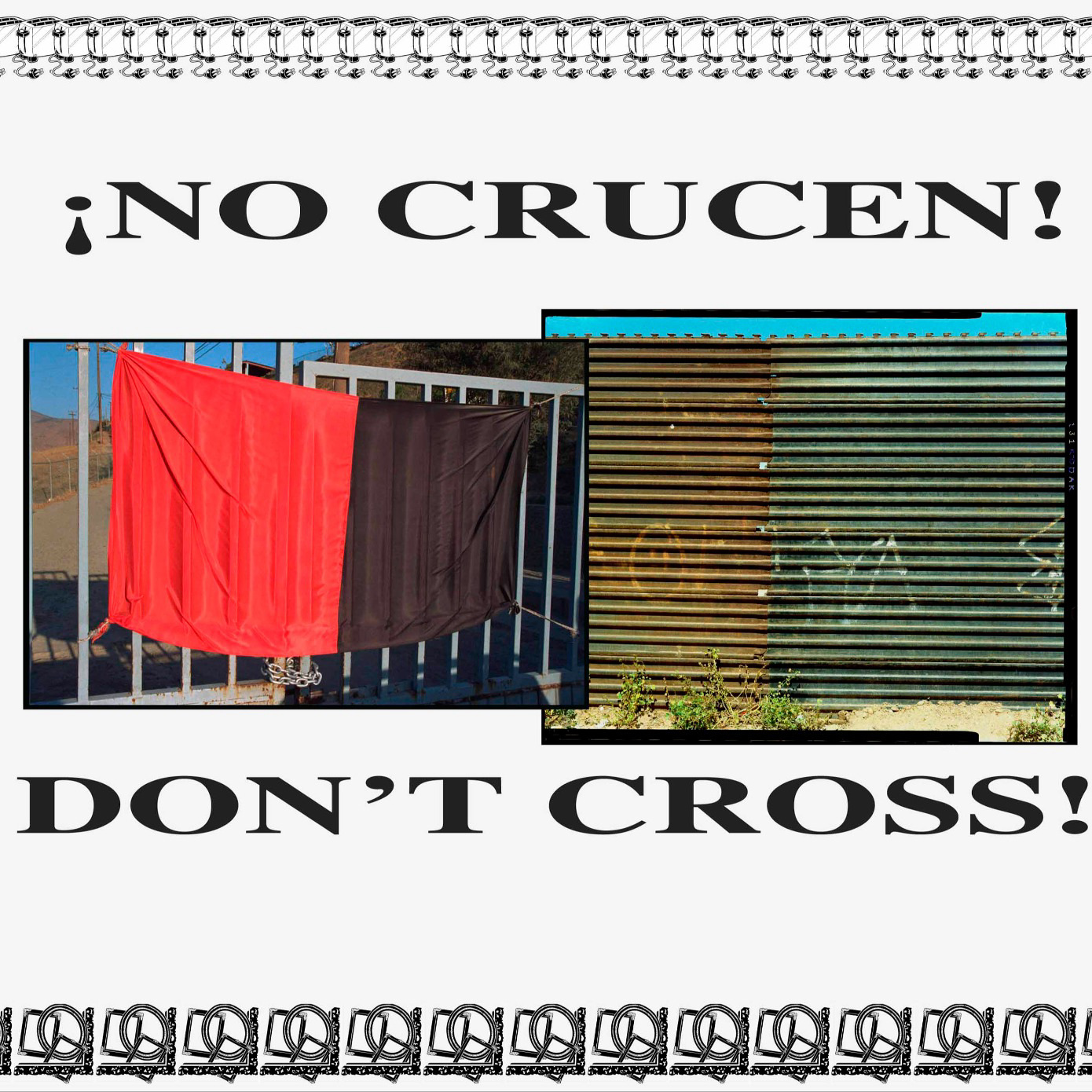

They also seemed to be community avatars, constructed, in part, to deliver a message of dissent. Procession, punctuated by moments of juvenile humor (the artist rigged one figure to appear to fart), was about the general obscenity of American politics—and the specific outrage of dirty money in art patronage. Known in some circles as “the Teargas Biennial,” that year’s edition of the Whitney’s storied show was roiled by protests demanding the removal of the museum’s then vice-chairman Warren B. Kanders, following revelations that he profited from the manufacture of chemical weapons, as well as from—the group Forensic Architecture later determined—sniper bullets used by the IDF against civilian protestors in Gaza. This past year, Eisenman has been a prominent, oft-cited voice for Palestinian liberation in the art world, speaking—not without repercussions—against Israel’s unrelenting destruction of Gaza. I suppose I expected to find her, with Fixed Crane, again using a figurative vignette to launch a rebuke, whatever her chosen target. I was intrigued to find that the lumpy white flag is the work’s only “person” visible from the exterior.

This time, Eisenman’s political commentary begins elsewhere. A line from the press text emphasizes the work’s participation in a Duchampian lineage, noting that Fixed Crane shows her “expanding her explorations of the 20th-century concept of the ‘readymade.’” It seems to ask us not to think of the crane, despite its weathered patina, as a found object—as something carrying a historical residue or psychic charge through human use—but to regard it, instead, as a urinal, so to speak. Duchamp’s renowned statement “talks only about art, the art system, art values,” as Indiana wrote (the critic’s “only” is extreme, inserted for drama, I think). Eisenman’s crane, on its side, on a public lawn, talks along similar lines—it articulates an impersonal, civic-minded, systems-and-values critique. Then, it does other things.

To end the impromptu tour of her piece, Eisenman urged me to “look in the slot.” A small panel in the back of the crane’s cab slides open, thrillingly, to reveal a cozy scene. A sculpted figure, a blanket around its shoulders, slouches by a wood-burning stove, as it—spoiler alert—roasts a weenie on a stick. Gober’s urinals, invested with traumatic, somatic, and sexual allusions via their laborious artisanal construction, “tell you about pissing, standing next to other people pissing, about cocks and having one or not,” per Indiana; Eisenman’s handwrought elements—in a sense—do too. She nods at the cock—the hotdog, the skyscraper, the bomb—as the crudest sign of power; she uses her most humbly fabricated elements to take her already-fallen monument down another peg, quietly guffawing at the crane as a kind of phallic kitsch.

The evening of the work’s public opening, I returned to the park for Ryan Ponder McNamara’s performance. Dressed in go-go construction worker attire, he enlisted members of the crowd to compete in an interpretative dance contest. Their challenge: to represent civilization’s progress—as well as its hiccups and savage regressions—since the Enlightenment. Each volunteer improvised a sequence of moves as they traveled down the length of the crane, using it as a climbing structure or kind of barre. I couldn’t see the dancers well from my vantage, but the thrust of McNamara’s argument was clear. The event—sexy, after sunset—drew out the double entendres and queer-coded details of Eisenman’s all-ages sculpture, while it illuminated the myth of advancement that drives urban misery.

Indiana, at the Voice, was tasked with covering the Reagan-era art boom, during the Reagan-era of mass death. As the new galleries of the East Village scene, often peddling a strain of Neo-expressionist painting he despised, ushered in a phase of rapid gentrification, AIDS stole his friends away. He would not pretend it wasn’t happening; in his writing, he didn't cordon it off.

It’s not a stretch to find connections, to draw a line from the desperate '80s to our vile today. The end of October 2024 was a dreadful time already, before this loss, with no arms embargo or ceasefire in sight and the election drawing near. Reading Indiana offers us no comfort, and I’m sure he’d hate to be regarded as a model. But his work does suggest a possible approach, suitable to our era—to write about what you love by way of what you hate. A racist landlord holds a rally for fascists at Madison Square Garden; an artist, speaking for the rest of us, topples a crane in Madison Square Park.