What does it mean to come home?

Anselm Kiefer’s show "Mein Rhein," on view at Thaddaeus Ropac's Salzburg Villa Kast location through Sept. 28, opens with fanciful images from his childhood: a boat, a house, a forest. I’m told he’s in the process of renovating his actual childhood home, recreating as best he can the abode he remembers from his youth. It's an impossible, nostalgic compulsion.

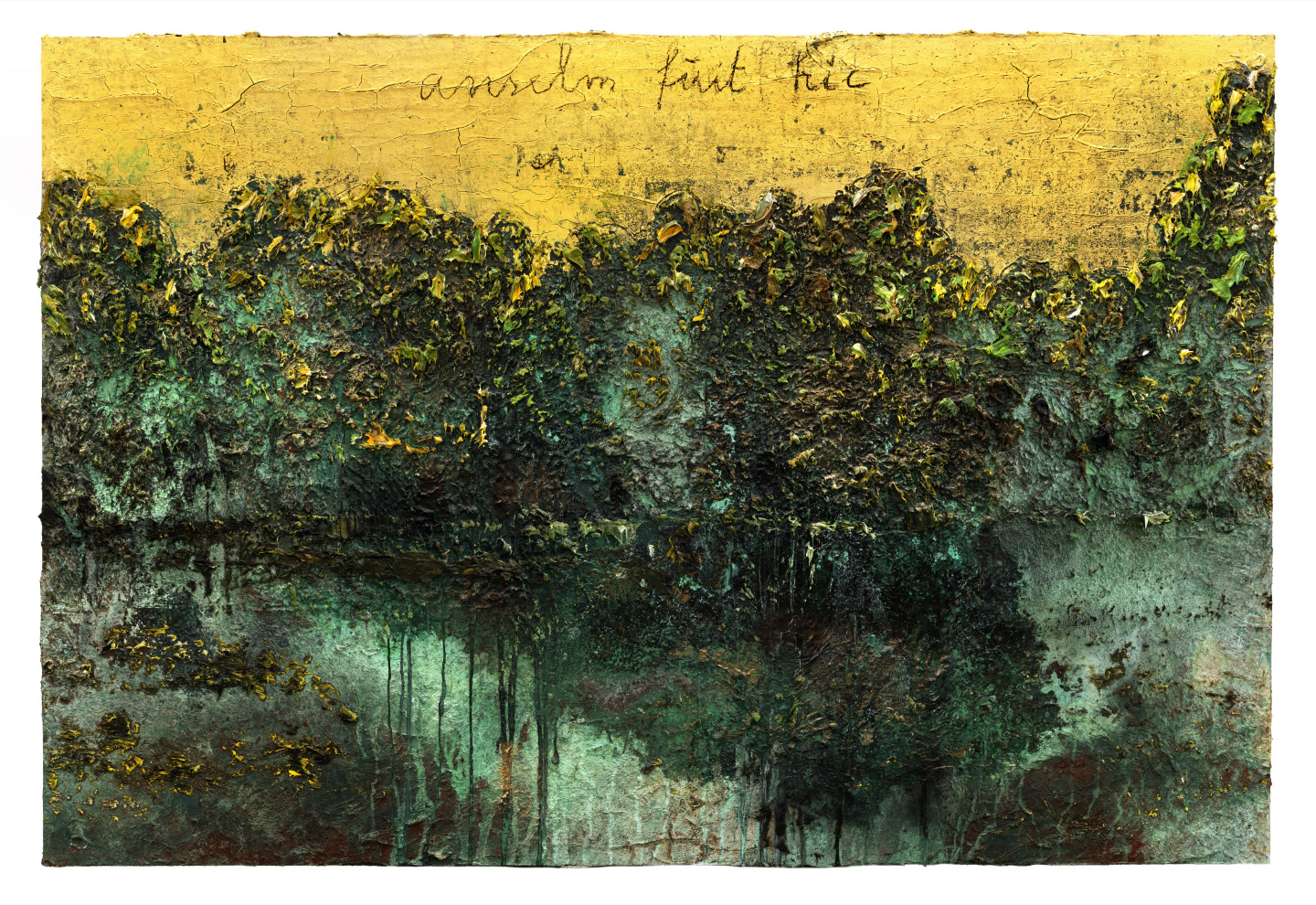

In the following rooms, we’re ushered into an older Kiefer’s meditations on the river of his childhood, the Rhine, which gives the exhibition its title. His canvases are covered with thick layers of sediment created through a process of transformation with heat, electrolysis, and time, the materials of the painting turned rust-red or vermillion green, cracking under the stress of chemical reaction. Thick daubs of paint and gold leaf are added to the work, the gold leaf at times attached with a bond so flimsy you could imagine a slight wind knocking it off and sending it floating down to the floor, like the leaves it’s meant to represent.

All this sediment, this accumulation. The leaves piled thick on the forest floor, spilling and rotting into the river, like a lifetime of memories, of associations. Kiefer in his youth heard old Nazi tales about the gold to be found at the bottom of the Rhine, sunken treasure, but rather than gold, the river in one of his paintings blooms blood red. Here, gold streams down from the sky instead, sending leaves ablaze with warm backlight.

Alchemists once chased the secret of chrysopoeia, the process of transforming lead into gold. In the hermetic tradition, this process was not seen as simply chemical; it was believed to have a spiritual meaning as well. The metal lead was associated with the planet Saturn—the father, Prima Matera, base matter. Gold, in turn, was associated with the Sun—the self, Apollo, purity, and perfection. An alchemist who studied those esoteric methods which claimed to turn lead to gold was learning not just to manipulate the physical matter around himself, but how to transform his very soul.

A grinning figure from Kiefer’s past paintings appears, perhaps a past self, a figure from his earlier years as an artist. These woods are at turns peaceful and malevolent. One can imagine Kiefer walking the same forest path he paced as a young boy, wearing down the leaves underfoot, trying to make sense of his memories to situate his present. He’s turning 80 next year, an age when one’s internal sense of coherent self begins to decay, but he’s still working, still making sense of the world. Kiefer’s past output leaned heavily on the symbolism of using lead as material. Now, in the process of revisiting his childhood, he’s uncovering new meaning: at long last, he’s turned to gold.

in your life?

in your life?