Buck Ellison has always confronted the “Abercrombie gaze,” even before he picked up a camera.

“As anyone born in 1987, I was influenced by [it],” the photographer says. He cites Bruce Weber’s instrumental influence on the now-classic if fraught aesthetic: Ultra conventionally attractive models chiseled within an inch of their lives, in-your-face sexiness, overwhelmingly white. The effect this look creates is an uneasy, at times downright creepy one, which Ellison knows well, recalling the allure of a similarly branded Ralph Lauren underwear box. “There was this feeling of being a young gay kid and wanting that image then feeling ashamed, even scared of what that desire meant. It's central to my practice, this push-pull with every image,” he adds.

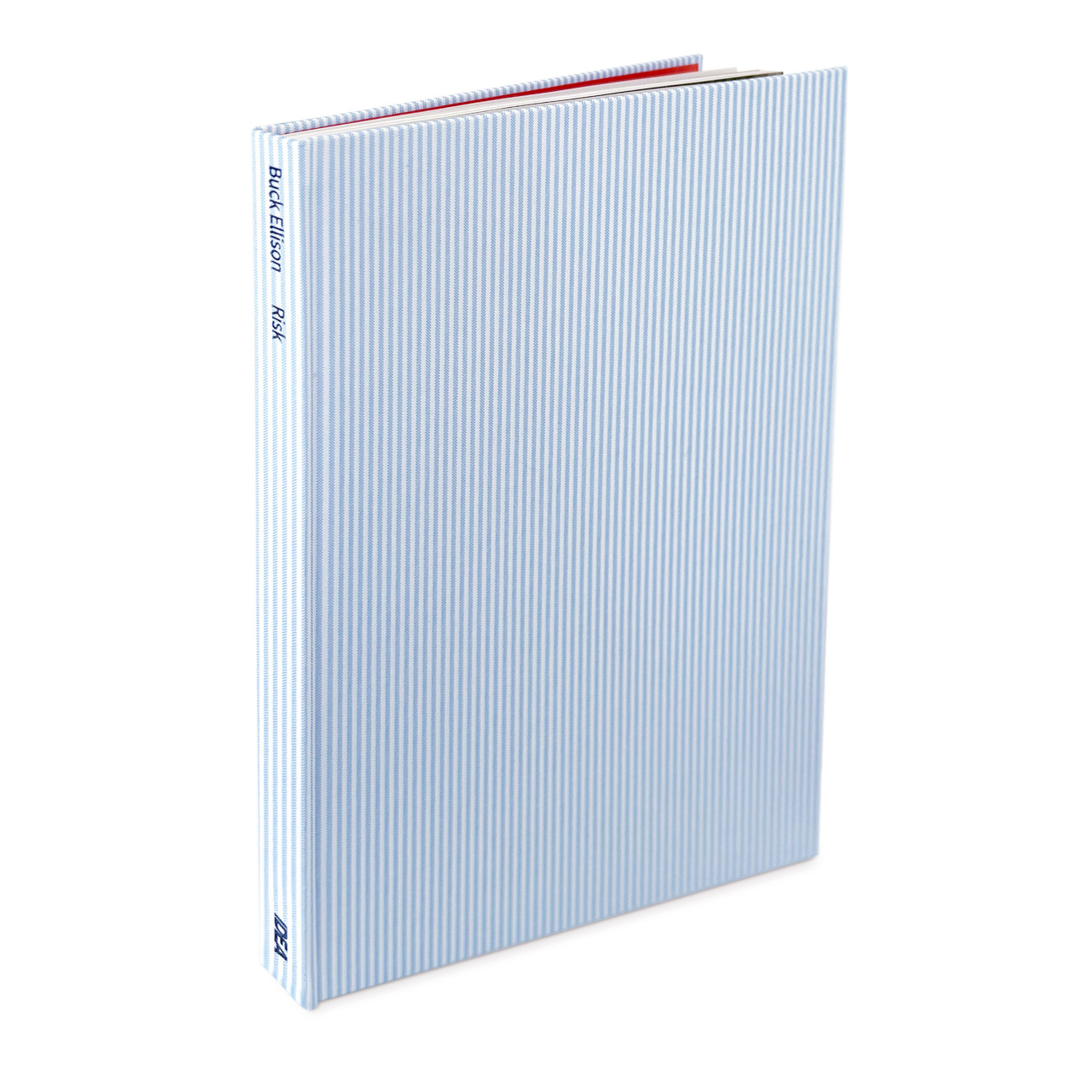

With RISK, Ellison’s fourth solo photography book and first with IDEA Books, the photographer hones in on clothing as it relates to whiteness and the enticement and eeriness therein. Whether unpacking the fraught history of lacrosse or recreating scenes of marital strife between Betsy DeVos and her husband, Ellison deftly turns scenes of mundanity into uncanny images.

To mark RISK’s publication, Ellison sat down with CULTURED to talk about the discourse of discomfort, his love of Lilly Pulitzer, and three images that encapsulate the book's troubling themes.

CULTURED: How is this book a departure from your previous ones?

Buck Ellison: My whole practice is a search and rescue mission—you go in circles apparently when you do that to cover a forest—so it feels like each thing is getting more precise. I've always been interested in making the silent security of whiteness visible, particularly how that's maintained through gesture.

This book was an invitation to flesh out the role of clothing. We printed the book specially to look like a shirt I owned. It’s called the Bengal stripe, which was a popular shirting pattern in England from the 17th century onward, but it originated from the Bengal province in India. Bengal Lancers, who were a regiment of the British East India Company, came in and saw these beautiful striped cottons, which are an indigenous product from that region, and started wearing it as part of their uniform. That came back to England and became fashionable for gentlemen to wear on business and formal occasions, which continues to this day.

CULTURED: How did you arrive at the title of RISK?

Ellison: The design borrows a lot from financial reports and prospectus documents, particularly from wealth management departments of banks. Risk is a finance term. It was an intuitive choice.

CULTURED: What's the riskiest thing you've ever done?

Ellison: All the work makes me really uncomfortable. It's a sign that I'm getting close to what I want, but it does keep me up at night. The images are only effective when they sit in ambivalence, when the viewer is invited to be like, “What the fuck are these white people doing…” I want the image to mirror how whiteness presents itself as bland and harmless, even slightly noble, but is actually extractive and violent. Risk, for me, is the sense of knowing that the images themselves must leave people with a lot of questions about my motivations as a person and an artist. That's difficult as someone who cares what people think, particularly about my politics.

CULTURED: Do you engage with the discourse of discomfort?

Ellison: If I wanted to hammer out my politics, I would be a writer. I made a choice to be an artist and to work with photography, which is mute. The image absorbs all this ambivalence. That's when I think they're most effective at starting a conversation about whiteness.

CULTURED: Beyond the images, are there some details in this book that you don't want people to overlook?

Ellison: The parts that I'm most proud of are in the back. We used the design to organize both the list of works and the CV. With the latter, alongside information about which exhibitions I had in each year, I included financial global events and financial aspects of my own biography. In 2016, I had an exhibition at the Index Foundation for Contemporary Art in Stockholm. Betsy DeVos also became the 11th U.S. Secretary of Education and vows to take an annual salary of $1.

Then in 2020, the United States Small Business Administration gave the S-Corp for my studio a loan of $71,000 through U.S. Bank with an interest rate of 1 percent. Precarity is a big conversation when we talk about artists, and if my work is going to be about highlighting the structures that uphold wealth and inequality, then I should turn that on myself and talk about the mechanics of the studio, what allows me to stay alive and to produce work.

We pulled the fonts directly from prospectuses, which are really beautiful in and of their own right. The font is Garamond, and when you're printing massive amounts of documents to hand out to shareholders, it uses the least amount of ink. We also used a sans serif throughout the book, which was difficult for me because it's gross. In order to replicate the financial design, I had to turn off parts of my own taste. That took a bit of adjusting to.

Buck Ellison's Key Images:

Hotchkiss v. Taft #1, 2017.

"[This is] the only work of mine that's not staged. All the photographs are from one game between two schools, Hotchkiss School and the Taft School. Hotchkiss was founded by the estranged former wife of the Hotchkiss fortune, which produced many things, like automobiles and staplers, but they also produced a form of revolving cannon that was crucial in the massacre at Wounded Knee. In a very literal sense, the family business was involved in the genocide of Native Americans, and the Taft family is a political dynasty.

Lacrosse is a Native American stickball game sometimes called the 'little brother of war.' I was interested in shooting the girls because in women's lacrosse you don't wear pads, and it's argued to be closer to the Native American sport. There’s an interesting juxtaposition because you're beating each other with sticks—it's extremely violent and dangerous—yet you're wearing a skirt. Sometimes with braids and face paint, you get these ghostly echoes of the original communities that played. I don't think we necessarily see women of this age and potentially even this group of people expressing real aggression and violence physically like this."

Dick and Betsy, The Ritz-Carlton, Dallas, Texas, 1984, 2019.

"This is Betsy DeVos pregnant with her first child, Alyssa, at the Ritz-Carlton in Dallas where they held the Republican National Convention. She was the chairperson that year. The DeVos family and the Prince family are both quite involved in politics, yet it's always said that Betsy's the more political animal of the two. I really wanted to show someone who is known in her public appearances for this 'Midwest nice' politeness laying into somebody on the phone.

Not just as a negative thing: there's a lot of agency there. It's very intentional that she is in front of Dick and takes up the frame. Then the dress was just too good to pass up. I love Lilly Pulitzer—the evolution of that brand is quite interesting. She was a bad girl who wanted to make these shift dresses you could wear without underwear and walk around Palm Beach with no shoes on. Then it became—at least when I think of Lilly Pulitzer—mean girls at private high schools. And Betsy's always fake tanning so we did that, too."

Untitled (Spring), 2022.

"There's four still lives printed to scale in the back of the book. Initially, I was thinking about scrolls and having to move alongside an image to view it. Our eye cannot see things this wide without it blurring. Winter's the shortest, summer's the longest. Spring is a bit about wool skirts—back to skirts. On the left, there's these receipts for dry cleaning in a hotel: One of the legacies of the British Empire is that you go to some tropical former colonies and see students wearing wool British school uniforms. That's such a tidy encapsulation of this subtle violence, also the decorous spin that was given to this brutal systemic torture and suppression that the British Empire enacted on a third of the world at one point.

RISK has an appendix with information on the subjects and makers of the paintings. I've been really interested in thinking about who the people are that are in paintings from the 18th century in museums. How did you come to have the money to produce these? This is Alan Ramsey's Thomas, 2nd Baron Mansel of Margam with his Blackwood Half-Brothers and Sister, 1742. It's in the Tate Gallery in London: 'This painting depicts the four children of Anne Shovel, the daughter of a noted admiral. The eldest, Thomas, holds a gun. His father was commissioner of the treasury who invested heavily in the South Sea Company and Royal African Company. The other three children depicted are from Shovel's second marriage to John Blackwood, a member of the House of Commons who abducted and sold 199 people to the South Sea Company in 1730. He later became an art dealer.'"

in your life?

in your life?