CULTURED’s monthly column, Spatial Awareness, pulls back the curtain (just a little) on some of the most original voices working in architecture today.

Each year, the chief curator of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute, Andrew Bolton, makes a habit of tapping renowned architects for his department’s annual fashion showcase, one of the plummiest exhibition design commissions in the world. Elegant and innovative star turns include Shohei Shigematsu of OMA’s ethereal galleries for “Manus x Machina” and Diller Scofidio + Renfro’s technology-infused “Charles James: Beyond Fashion.”

Next up for Bolton is “Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion,” opening May 10. The multisensory extravaganza recontextualizes a selection of archival garments connected by the cyclical nature of birth and renewal. His architect of choice is Leong Leong, the New York-based studio founded in 2009 and helmed by brothers Chris and Dominic Leong.

Leong Leong has deep ties to the fashion world. The studio first made its global mark in retail with its 2009 design for 3.1 Phillip Lim’s freestanding Seoul store. Clad in puffy concrete tiles, the boutique remains iconic, despite having closed since. In the last decade, the scale-agnostic studio has produced imaginative cultural and civic work ranging from the minute (fermentation vessels exhibited at West Hollywood’s MAK Center for Art and Architecture) to the sprawling (a nearly 200,000-square-foot masterplan and design of the Anita May Rosenstein Campus, which serves the LGBTQ community in Los Angeles).

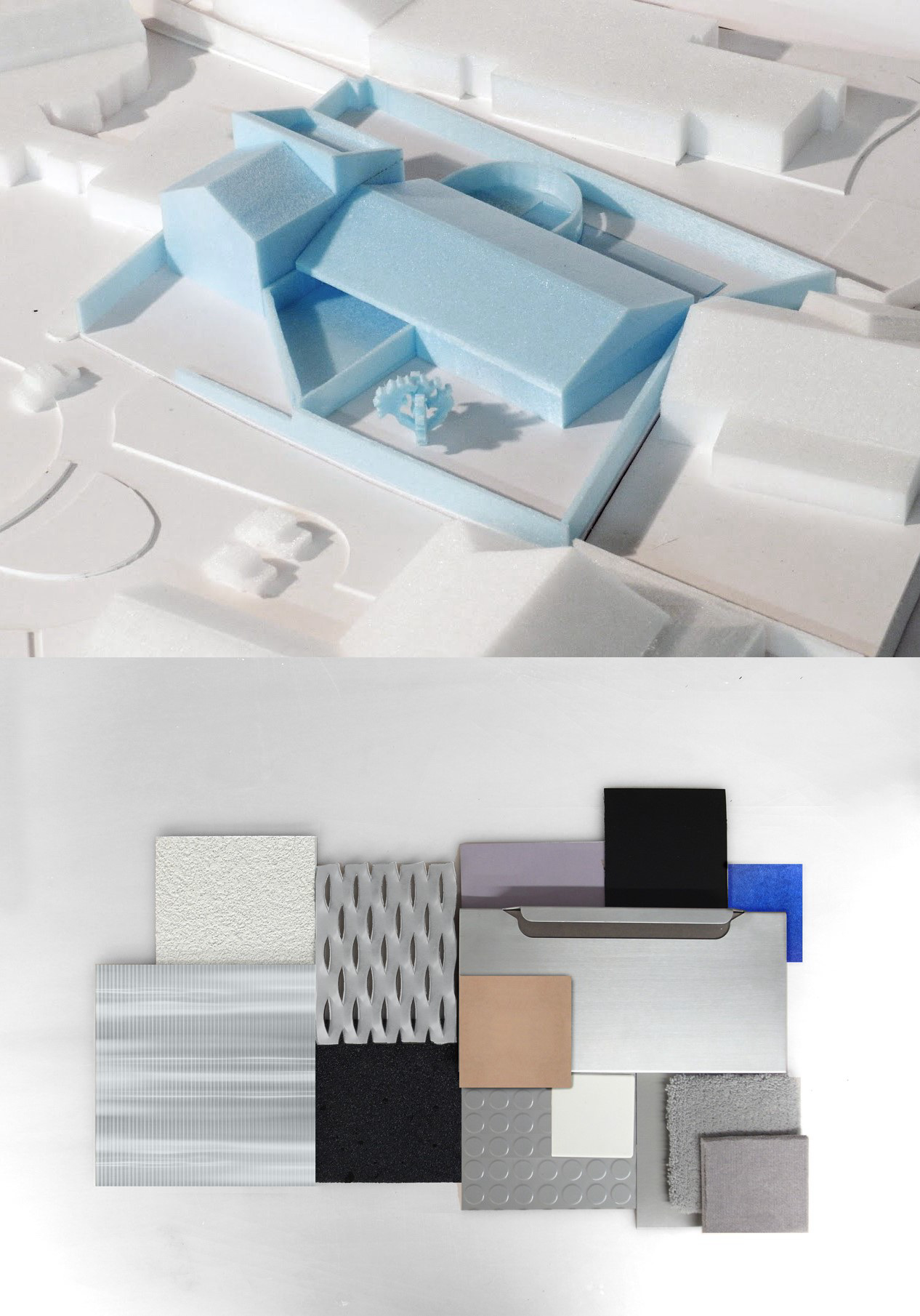

The Met’s fashion shows rank amongst the museum’s most visited exhibitions, making the forthcoming presentation one of the Leong brothers’ most prominent art-world gigs to date. While Dominic Leong relishes the enormous platform, his favorite moments of the creative process are early client conversations. In the case of “Sleeping Beauties,” he and Bolton bonded over numerous concepts engaging the body: a “body” of knowledge, fashion and the senses, form within space, and an embodied experience were all considered. These discussions led Leong Leong to develop an exhibition that is essentially “a building within a building” consisting of a network of domes for immersive activations and a garden-like area meant to expand your senses.

Leong’s office, in New York’s Chinatown neighborhood, is abuzz with projects across the nation. Angelenos, in particular, have become a loyal fan base. In the last year, the studio wrapped up a Melrose Hill gallery for James Fuentes and a house in Hancock Park for the founders of the gallery Various Small Fires. Leong orchestrates a conversation between the artworks and the architecture, neither overwhelming the other. In Philadelphia, the firm partnered with collector turned real estate developer Dasha Zhukova to open Ray Philly, a multifamily residential compound that aims to bring art into day-to-day life. The development hosts installations by Michelle Lopez and Rashid Johnson and features a promenade of artist studios, galleries, and shops.

Ideating on the best practices for serving artists runs in the family: Leong’s wife is renowned arts advocate Deana Haggag. The couple gather an intergenerational mix of artists, curators, poets, and writers for monthly dinner parties. Leong considers his friends the great communicators of the 21st century, oracles pointing the way toward the unexpected.

This familial energy and his ancestral roots have nourished Leong’s most personal project to date, Hālau Kūkulu Hawai‘i. Collaborating with artist Sean Connelly, Leong is focused on how architecture can work in service of advancing equitable ecological practices and cultural recovery across his Native Hawai‘i. They have embarked on developing a scalable Indigenous building system that supports community groups restoring native food systems like fishponds and taro fields.

It's refreshing to reconnect to the word “Aloha” beyond the facile context of Hollywood rom coms. The greeting translates to love and fellowship, and Leong’s life’s work is to treat people and land with reverence.

IN HIS OWN WORDS

What was your favorite toy growing up?

Nature was my playground. I found a lot of joy in the landscapes where I grew up in Northern California and visiting family in Hawaiʻi.

Whose house would you live in (real or fictional) and why?

I’ve been working on a fictional house for the last eight years. It’s called “The House Before the Departure from Earth.” The idea is to design a house as a landscape of domestic objects that reconnect us to our bodies, give us a sense of time, and locate us in the present.

The objects are designed for rituals of care like vessels for fermentation, a rocking stool, and a floating tank. Parts of the “house” have been in exhibitions at the Schindler House [in Los Angeles] and the Guggenheim Bilbao. But maybe someday they will become a real house!

What is your go-to uniform when you're powering through a project?

It’s not very original—I have a stack of Margiela sweaters and two pairs of Rick Owens’s Birkenstocks.

Who chooses the playlist in your studio?

Nobody. It’s 2024, everyone wears headphones. But maybe we should bring it back.

What’s a trend in architecture you wish would die out?

I think terrazzo has had a good run…

What is one detail of a structure that most people wouldn't notice, but that you always look to for insight?

I’ve always been obsessed with materials that feel a little strange or unexpected. As I’ve matured as an architect, the provenance of materials, how they are made, and who produces them are equally important as their aesthetic qualities. It’s very similar to understanding where your dinner comes from. Architecture has a lot of similarities to food as a cultural and material practice.

Are there any analog materials you return to in spite of the prevalence of new technologies?

Yeah, I’d prefer an architecture that feels analog even though it may have been designed or made with the latest technologies. The idea is to evolve Indigenous construction methods with new technologies to meet the needs of contemporary programs that require different types and scale of spaces. It’s an approach to materiality that is inseparable from ecology and cultural meaning.

What is the most progressive architectural city you’ve visited?

I can’t think of a single city but the most progressive ideas driving the next wave of sustainability, or what’s been named “regenerative design,” remind me of the ways of knowing that Native communities have protected for centuries before they were erased. Is there a contemporary city that gives back more than it takes from the land? That’s what we need to keep working towards.

What is your last source of inspiration that surprised you?

I just read a book by the scholar Hi′ilei Julia Kawehipuaakahaopulani Hobart titled Cooling the Tropics. It’s an incredible account of how the introduction of ice in the mid-19th century reshaped Hawaiʻi’s food system and urban infrastructure. We take ice for granted but the thermal technologies it necessitated changed cultures and transformed the built environment. This history is very relevant for how we navigate the future.

in your life?

in your life?