CULTURED’s monthly column, Spatial Awareness, is meant to pull back the curtain (just a little) on some of the most original voices working in architecture today.

If you are familiar with the design studio LOT-EK, you probably know them as “that duo obsessed with shipping containers.” But you'd be boxing them in if you stopped there.

Over the past 30 years, Neapolitans Ada Tolla and Giuseppe Lignano have built an intimate and unique architectural language by upcycling not only the humble corrugated steel container, but also oil tanks, cement-mixer drums, and airplane parts. The New York Times has called them “the high priest and priestess of industrial chic.”

More akin to an art practice than a conventional architecture operation, their work stretches the boundaries of adaptive reuse with rigor and imagination. Uniqlo and Puma pop-ups? Sure. Four-bedroom house in Brooklyn? You bet. A 70,000-square-foot live-work building consisting of dozens of micro-apartments in Johannesburg? Why not! An extreme sports camp in China? A schoolhouse in New Orleans? You get the picture. They relish any challenge, and the breadth of their work is formidable.

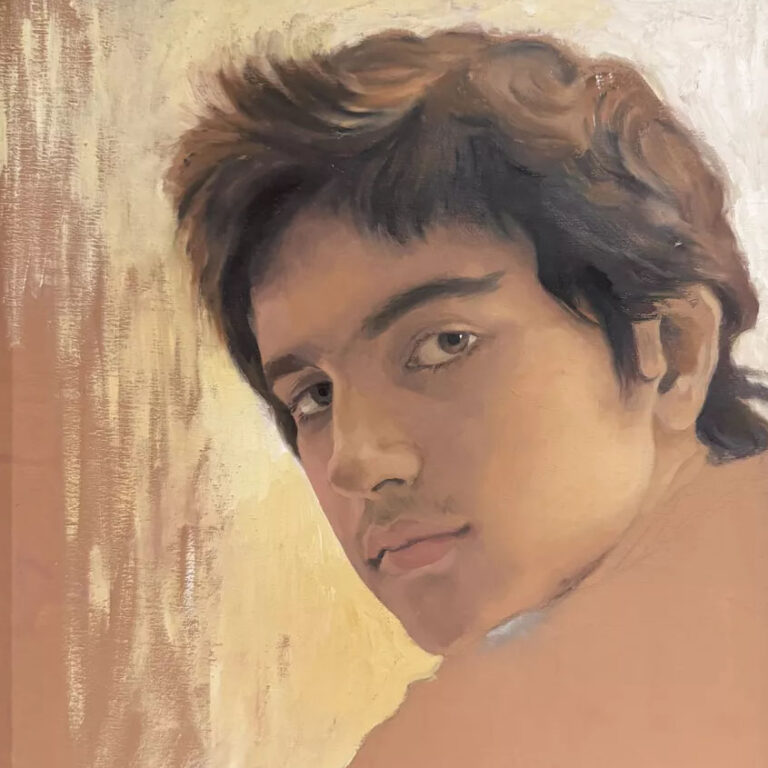

The duo is the subject of documentarian Thomas Piper's intimate portrait We Start With The Things We Find: The LOT-EK Movie. Shot over the course of a decade and released last year, the film is populated with endearing scenes of the two friends, who became inseparable as students at Universitá di Napoli in the late '80s and now run their studio out of a storefront in the East Village.

As they inspect a shipping yard stacked high with containers, their enthusiasm for what Tolla categorizes as a “leftover” is contagious. Tolla summarizes the film as an opportunity to reflect and contemplate the cycle of making and disposing. With more than a dozen screenings scheduled across the nation this year, LOT-EK anticipates the film will debut on a streaming service in early 2025.

LOT-EK has made their name by taking a symbol of globalization—the shipping container—and breaking, cutting, and cropping it to create designs that are responsive to their locales. No project better serves this brand of creative reclamation than the Cubes at Socrates Sculpture Park in Queens, New York, which opens to the public this month.

The project’s origins stretch back to 2012, when the Whitney Museum commissioned LOT-EK to design an educational annex in the "moat" between the sidewalk and the Brutalist Breuer building on Madison Avenue. The double-height, six-container building provided 700 square feet of flexible space for art-making classes, talks, and special exhibitions. The Whitney's move downtown in 2015 prompted the structure's donation to Socrates.

To adapt the construction to its new location, LOT-EK affixed 12 containers to the original six, forming a new scheme housing administrative offices and educational programming. The first permanent structure in the park, the Cubes provide essential year-round indoor space for the community and Socrates team.

The Cubes project is a full-circle moment for Tolla, who years ago ventured often to Socrates with her young son. They took full advantage of the outdoor programming, including kite-making, planting in the garden, and building small furniture from scraps. It’s this scrappiness, ingenuity, and humanity that makes the ethos of LOT-EK and the sculpture park align perfectly.

IN HER OWN WORDS

What was your favorite toy growing up?

Not many toys back then—we were a band, a big family, definitely more into playing games than into toys. Hide and seek was a favorite.

Whose house would you live in (real or fictional) and why?

I’m not interested in living in a house; I’m a city creature. I’m intrigued by the idea of living on a different matter than soil—as in floating homes (think: Seattle) or tree houses. Taking the latter to fiction, I’d love to set this treehouse on a billboard—one of those triangular, tall, and large billboards. Back into urbanity.

What is your go-to uniform when you're powering through a project?

Black jeans and black wool sweater, boots, and a scarf around my neck for color.

Who chooses the playlist in your studio?

Tala [Salman] and Reza [Zia]. It’s a broad range, from Italian '60s pop to experimental contemporary Middle Eastern.

What’s a trend in architecture you wish would die out?

I wish trends died out altogether. We have such powerful creativity and intuition, and the potential to expand what’s right, beautiful, or cool.

What is one detail of a structure that most people wouldn't notice, but that you always look to for insight?

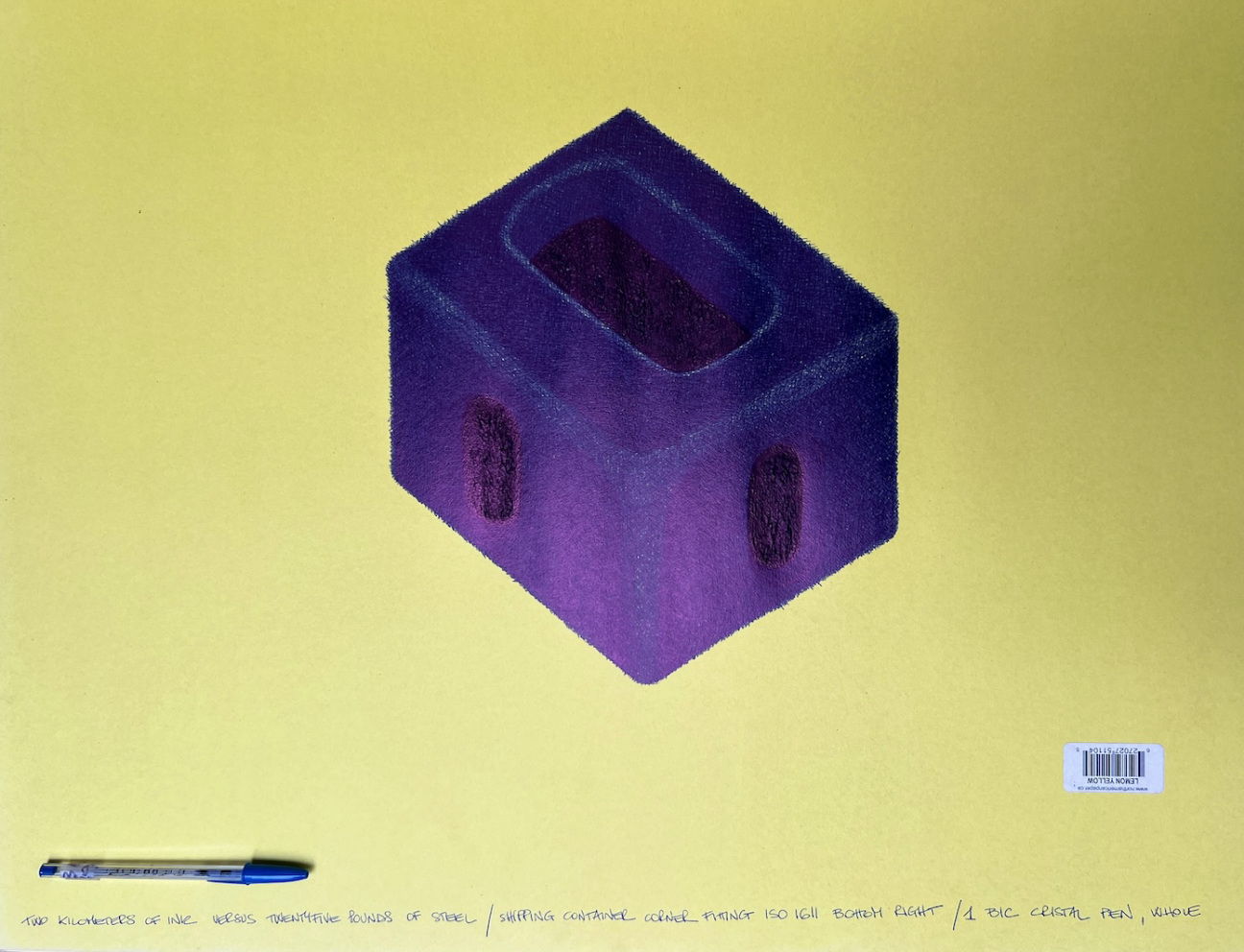

Mechanical connections and mechanisms.

Are there any analog materials you return to in spite of the prevalence of new technologies?

Cardboard boxes, scissors, and paper, possibly the back side of bad prints, our old and useless letterhead, leftovers. Leftovers are my go-to for anything creative, from making food to building a chair or a lamp.

What is the most progressive architectural city you’ve visited?

I’m interested in cities that can hold differences and contrasts, and are rich with complex humanity. I consider “progressive” cities with everyone and everything. Cities where issues are in the light rather than removed, out of sight. My hometowns of New York and Napoli are models of great humanity and a constant work in progress.

What is your last source of inspiration that surprised you?

The floor. The sidewalk, the road, the gutter along it. I’m always on a bicycle and scanning city grounds has been inspiring. SPILL [a 2023 installation made from a shipping container cut into 29 pieces] started with noticing the power of things crashed on the bike path, the glimmer of glass particles, the cracked shape of broken bottles barely held by their sticky labels, the color of a pink plastic cup shattered against the black asphalt.

in your life?

in your life?