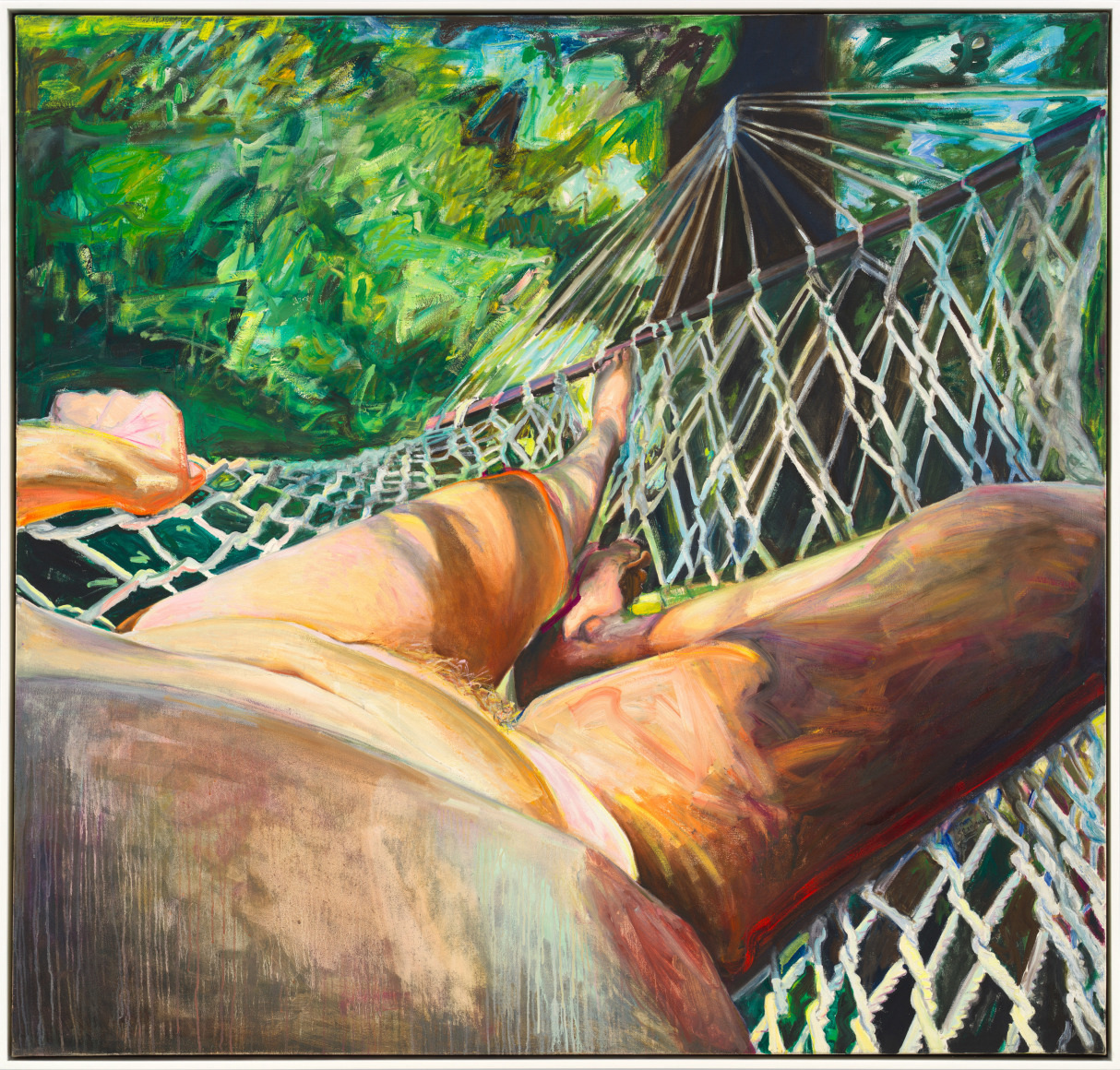

Joan Semmel’s exploration of one of art history’s longest figurative traditions—the nude—has made her a flagpole of feminist art for the past five decades.

From her unflinchingly coital “Sex Paintings” to her recent dissections of the aging female form—which will be featured in her first exhibition with Xavier Hufkens this April—the native New Yorker, now 91, is unrelenting in her dedication to distilling the experience of occupying a body.

CULTURED: When did you start making art?

Joan Semmel: I began working as a child, essentially. I was a sickly child, and I did it to amuse myself. It was just making images with whatever was at hand. My mother was told by a teacher that I was talented and should apply to the High School of Music and Art. So that's where I entered my “career” as an artist.

CULTURED: Do you remember some of the things you were interested in making at the time?

Semmel: I did what most children do: I copied things. I copied the comics. I made these doodles all over my notebooks all the time. It was just an obsessive creation of imagery of one kind or another. There wasn't anything particular. I didn't think of myself as an artist. It was just something that I did.

CULTURED: After high school, you decided to attend Cooper Union. How did those years affect how you understood art and the art world?

Semmel: That was the point where I decided I wanted to be an artist. Cooper Union at that point did not even give a degree. It was a three-year course. Whereas if I had gone to school at one of the city colleges, I would have been getting a degree, perhaps in teaching or art history even. It would not have been primary training as an artist.

CULTURED: What were the challenges of that experience?

Semmel: There was a lot of work. I remember being up nights doing all the assignments and so on. It was a very rigorous program, and a sizable percentage of the people who went in never got through it. In other words, they dropped out after the first year. But I never wanted to drop out. I was determined to succeed.

CULTURED: After Cooper Union, you married and stopped making work for a while.

Semmel: And I had a child. I wanted to have a “normal” life, not the life of a "starving artist." I became a housewife, so to speak. Then I got sick; I had a round of tuberculosis and was hospitalized for about six months. That was the point, I think, where I decided that I wanted a life in art. It was about [building] a sense of myself as separate from the family, that I had my own life and my own identity that went beyond whatever function I fulfilled as a wife-mother. That was my way of insisting on my own identity.

CULTURED: Is that still the case today? You've depicted your own body for decades now. Is it a way to insist that you still exist?

Semmel: I used my own body because I did not want to objectify another woman. I wanted it to be not an idealized form, but a real body—the way a woman actually understands her body. It's not a portrait or a picture of me. It's just that instead of hiring a model, I used my own self as that model.

And I did not only do that. I just did a retrospective two years ago, and you can see the transition of my work through various series of imagery. I worked first as an abstract painter, then I did a whole series of sexual work. Then I did my own body, but then I did portraits and works in the locker room. All of the work has been about the concept of a woman's artist making art that comes from her own experience rather than from what the male hierarchy gives her as the model to follow.

CULTURED: The nude is also a throughline in your work.

Semmel: The reason I used nude was because in the history of art, the nude is a genre that has been an important icon for women and even for movie images, for advertising—the whole concept of what a woman is.

I wasn't being provocative just for the sake of being provocative. I was trying to change the way women are seen and are disempowered culturally.

CULTURED: When do you think your practice found its audience?

Semmel: My work was always about the audience of one, of myself. I didn't look for an audience. I painted what was important to me, and it had to find its own audience.

CULTURED: What advice would you give to a young artist who admires you?

Semmel: Making art is a long road. It doesn't happen overnight. You change and you grow and you learn. During that whole process, you have to have a personality that can absorb rejection. You have to be able to work without acclimation many times and have the confidence that what you do is important and worth doing. And if you don't have those things, you're going to drop out.

Making art is a compulsion. There’s not anything logical about it. Years ago, we said it was a calling. Now young people think about a career. A career as an artist, there's no such thing. You're an artist because that's who you are. That's what you need to do. You do it because you're obsessive about doing it. I mean, if an artist is always working towards a career, they'll have a flurry for a while but then it passes. So how do they sustain themselves then? It has to come from something internal.

This interview is part of a series of conversations with female artists over the age of 75. To read more, see this article on Pippa Garner, the artist who's held a zany mirror to American consumerist culture for over 50 years; or this story on Sonia Gomes, who left a legal career to become an artist at 45.