On Christmas Day 1924, Georges Rouy passed away. The French botanist was a prolific scientific writer and researcher, allegedly the first to introduce the taxonomic groups of subspecies, varieties, and forms to the field. Seventy years after his death, George Rouy was born in the industrial British town of Sittingbourne. If the former made a career out of dividing and classifying the minutiae of the plant world, the latter has devoted his to the disruption and blurring of figurative representation. What a difference a letter makes.

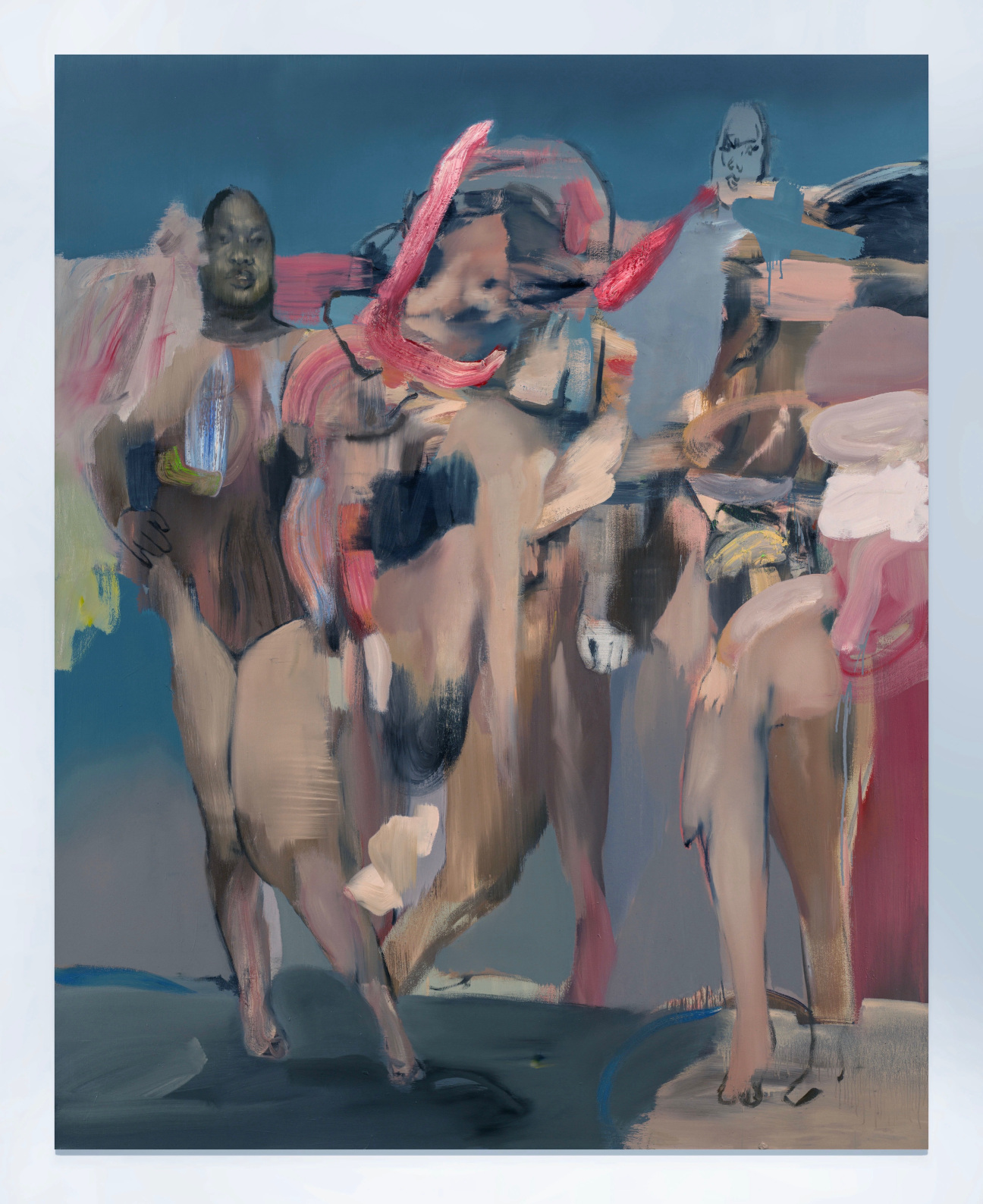

Since breaking into the art scene after graduating from London’s Camberwell College of Arts in 2015, Rouy has taken an almost totemic approach to his painterly study of the human form. Although his aesthetic forefathers have shifted from Fernando Botero to Albert Oehlen in the past eight years, the artist retains a faith in the double-edged sword of accessibility and opacity that depicting the body affords him. The glitchy, delirious, and sometimes claustrophobic polyphony of paintings that make up “Endless Song,” his solo show on view at New York’s Nicola Vassell Gallery, marks an exciting new chapter in Rouy’s anatomic dissertation. To honor its opening, CULTURED sat down with the London-based painter to discuss his process.

CULTURED: Where are you? How are you feeling ahead of the show?

George Rouy: I'm at my house. I live in a converted church. It’s a bit of a crazy house because I've been doing all these strange prototypes for furniture. I'm getting that all together which is fun. I finished the body of work for Nicola Vassell. The studio is so intense, it's quite a heavy energy sometimes. Every time I finish a body of work, I feel a weight being lifted. I used to have a low, where I would get a bit depressed, but now I have a new energy coming through where I can think of other creative things that aren’t painting.

CULTURED: Has painting become painful?

Rouy: I wouldn't say painful, I just think there's an element of pressure. Pressure’s a funny word, but there's a seriousness to the work that hangs over it—in a good way because I want to make paintings that have a certain presence. There are lots of twists and turns to get to where the work is now. Although there's a finished outcome, there are all these bits you're understanding as you go.

CULTURED: Tell me a bit about the series of paintings you'll be showing at Nicola Vassell. How is it a departure from previous presentations?

Rouy: This [summer], I had a show at Hannah Barry Gallery in London, so I was working on two bodies of work at the same time. What happens is that every painting informs the next one. I finished the series for Hannah, paintings that were heavily influenced by dance because there was going to be a performance in the space. There were a few weeks of really intense studio time where I was trying to understand new languages that I hadn't quite grasped yet, which had to do with movement, abstraction, and the body. I wanted to focus on a mass of figures that exist within this energized sequence.

The thing I've been trying to understand for quite a while is how gestural abstraction can be used to enhance the effects of a painting by breaking down the strict barriers of one's anatomy … The other day I was in the Louvre and I saw [Théodore Géricault’s] The Raft of Medusa, 1818-19, and I was like, “Fuck, it's got that dynamic kind of chaos.” You pick out different moments, and it feels like it's human essence. Something I've learned over time while painting is that the works are entirely about the human essence and everything that comes with it—the good things, the bad things, and things undefined.

CULTURED: You rely on existing photography as inspiration for your work. How are you sourcing these images, and when do you transition into painting?

Rouy: When I was at university, I was really into this Dada-esque way of repurposing existing material. At the time, I was really into Jeff Koons and artists who were reshuffling our awareness. Someone said to me once, "The paintings are familiar, but you don't know why." I thought that was a good way of putting it because I genuinely go on Google, accumulate odd images, and collage them. I put them in Photoshop, then I distort them, add bits, take bits away… Then they're so far removed from what the actual image was. From that moment on, I think to myself, This may be a good basis for a painting. There’s always a massive shift from the collage to the painting. I’m not trying to represent the photograph.

CULTURED: What about the human figure continues to draw you in?

Rouy: This year, I've been thinking a lot about the face within the paintings, and how the presence of a painting changes when you remove or abstract a face. I was really battling with it for a while; something felt off. It took a lot of time for me to gain confidence and have the paintings focus just on the body. With that, it becomes even less anchored. I always thought you needed these anchor points in a figurative painting—a face, hands… I’ll always keep my practice in the realm of figuration [though] because I think psychologically the work is best when it has that essence of the body. Once you go fully abstract, how do you go back? It’s like a K-hole of abstraction.

in your life?

in your life?