Andrew Cranston most enjoys solitary pursuits, like painting in his studio and golfing on his local links, which he considers more akin to land art than the ubiquitous manicured greens found elsewhere. Recently, though, the Scottish artist found himself in front of a large crowd that had congregated to hear him discuss his new body of work at Edinburgh’s Ingleby Gallery. He stood beneath the octagonal skylight of the gallery’s converted former Glasite Meeting House, where the Quaker-like sect would once invite any parishioner who “possesses the gift of edifying the brethren” to speak, and gathered his thoughts.

Cranston began by gesturing toward the center of one of his large paintings, identifying the composition as a riff on Paul Klee’s Garden scene with a watering can, 1905. Surrounding his take on the expressionist work—the row of four watering cans, the cat perched on the garden table, the matching red wire chair—is a walled garden that recalls the one Cranston and his wife, fellow painter Lorna Robertson, shared with their children throughout the Covid lockdowns. (“Painters love walls,” he noted.) Shocks of warm pink underpainting peek through the bucolic, sage-khaki scene, slowly drawing the eye across the composition and toward a ladder in one corner that hints at a possible escape.

As is clear in Walled garden (after Paul Klee), 2023, Cranston creates narrative scenes underpinned by single registers of color. While he is best known for painting the hardcovers of old books—poetic moments contained to a hand-held dimension—his current show at Ingleby presents a suite of canvases large enough that “you can step into them,” he explained during a walkthrough of the show organized in conjunction with the annual Edinburgh Art Festival.

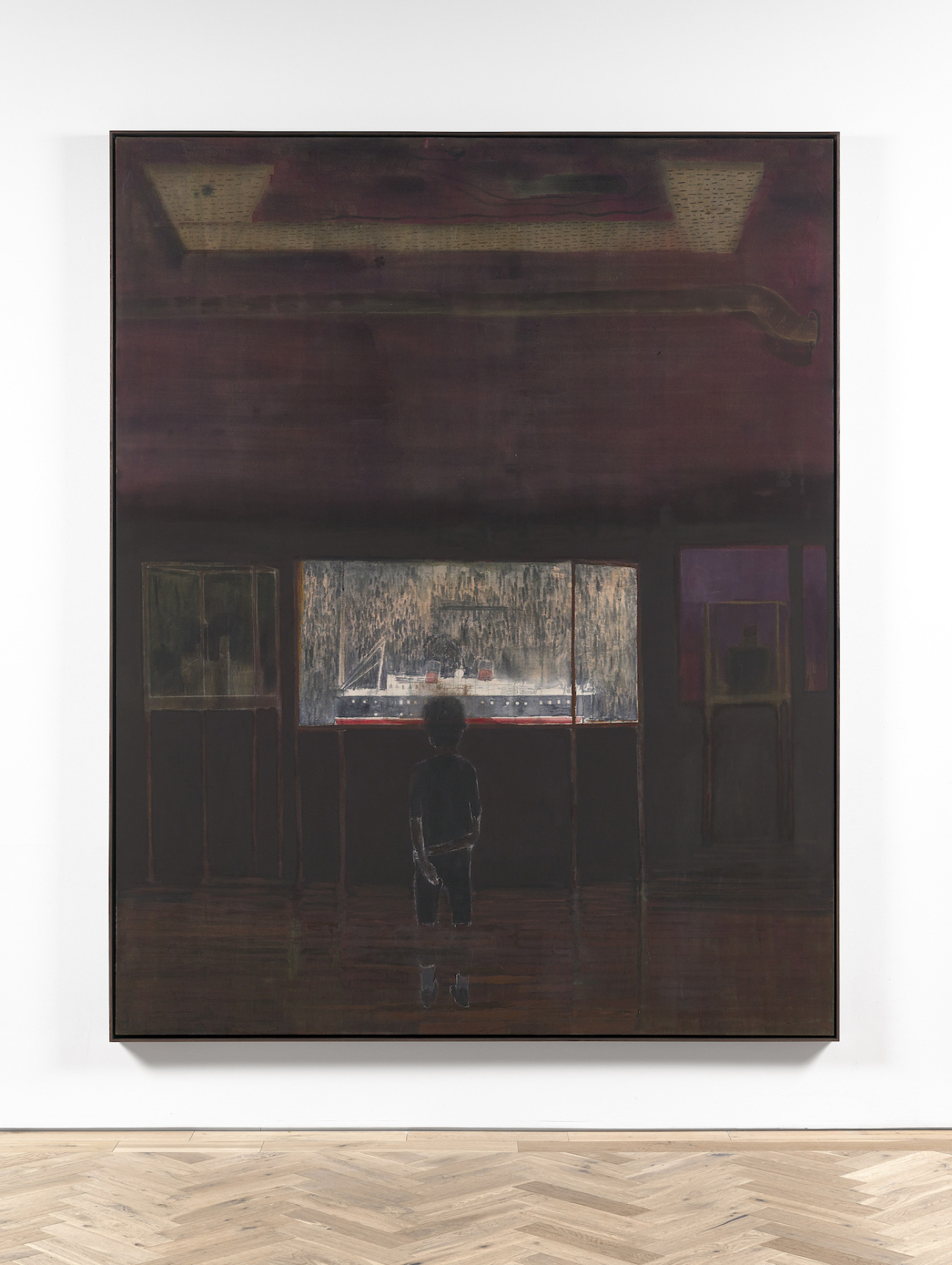

Cranston’s delicate balance of scale and hue is most evident in Questions of travel, 2023, a two-and-a-half-meter-tall picture that registers initially as horizontal squares of murky, inky aubergine. Its overwhelming quiet is reminiscent of Mark Rothko’s black and maroon "Seagram Murals" at Tate Modern. Before long, a figure comes into view: a young boy staring at a toy model of a steamship lit up inside a glass vitrine. Like much of the artist’s oeuvre, the scene is a collage of memory and fiction, depicting a now-nonexistent room in Glasgow’s old Transport Museum where shipwright pensioners would examine miniature copies of the massive steamers they helped construct. Always beginning paintings at their center, Cranston added the boy last: an echo of one of his now-grown sons, or, perhaps, of himself.

Why have you stopped here?, 2023—the only painting made expressly for the show in Edinburgh—memorializes another beloved and now transformed museum scene: the former fish pond at the National Museum of Scotland. (A recent renovation saw the tank’s removal from the museum’s atrium.) Working from a “jaundiced” ground, as he often does—finding yellow to be a “mysterious” color—Cranston gave the painting a foreboding undertone. The elongated fish forms are set to the grid as in “a game of battleship,” a reflection of the menace and dread that Cranston felt when he first began the pond series in the early aughts while listening to radio reports of the Second Gulf War.

Cranston is careful not to explain or demystify his work too much. The publication that accompanies the exhibition, Andrew Cranston: Never a Joiner, is not so much a catalog of the show—it includes none of the large pictures—as a collation of the artist’s ekphrastic musings on his smaller book-cover pieces. Though his daily work begins with writing, not painting, he insists, “I’d hate to be a writer.” We are fortunate that this self-effacement has not prevented Cranston from sharing his words.

The show’s title is similarly contradictory. While he opted to pursue the solitary vocation of painter in lieu of becoming a “joiner,” or millwork carpenter, following a yearlong apprenticeship as a young man, Cranston has nonetheless built a healthy following and community around his work. And he not only combines disparate influences and personal memories, but, in some cases, also quite literally binds compositions together. “This painting is two separate paintings conjoined,” he notes of Cat and cheeseboard, 2018, pictured on the book’s dust jacket: “I relish the joins which I want to keep visible.”

“Andrew Cranston: Never a Joiner” is on view through September 16, 2023 at Ingleby Gallery in Edinburgh.

in your life?

in your life?