“At long last, the battle has ended! And thus Ghana, your beloved country, is free forever.” Those were the first two sentences uttered by Ghana’s first prime minister, Kwame Nkrumah, on March 6, 1957 as he stood on the balcony of Accra’s old Polo Grounds and pronounced Ghana the first country in Africa to gain independence from colonial rule. “We are going to create our own African personality and identity,” continued Nkrumah. “It’s the only way we can show the world that we are ready for our own battles.”

As the Brooklyn Museum’s new exhibition “Africa Fashion” illustrates, clothes played a key role in creating this distinctly African personality and projecting it out into the world. By opting to wear agbadas, kente, and dashikis rather than suits, Nkrumah and his fellow politicians—Archie Casely-Hayford, Kojo Botsio, Komla Agbeli Gbedemah, and Krobo Edusei—rejected Ghana’s former colonizer, Britain, and presented their own image of what African identity might look like.

But this was just one moment in a much longer history. More than 65 years later, “Africa Fashion” has given itself a formidable task: to synthesize 70 years of creative expression across 50 African countries. It manages to do so in a way that is both inspiring and deeply informative by portraying fashion as a mechanism for identity-building rather than as an industry.

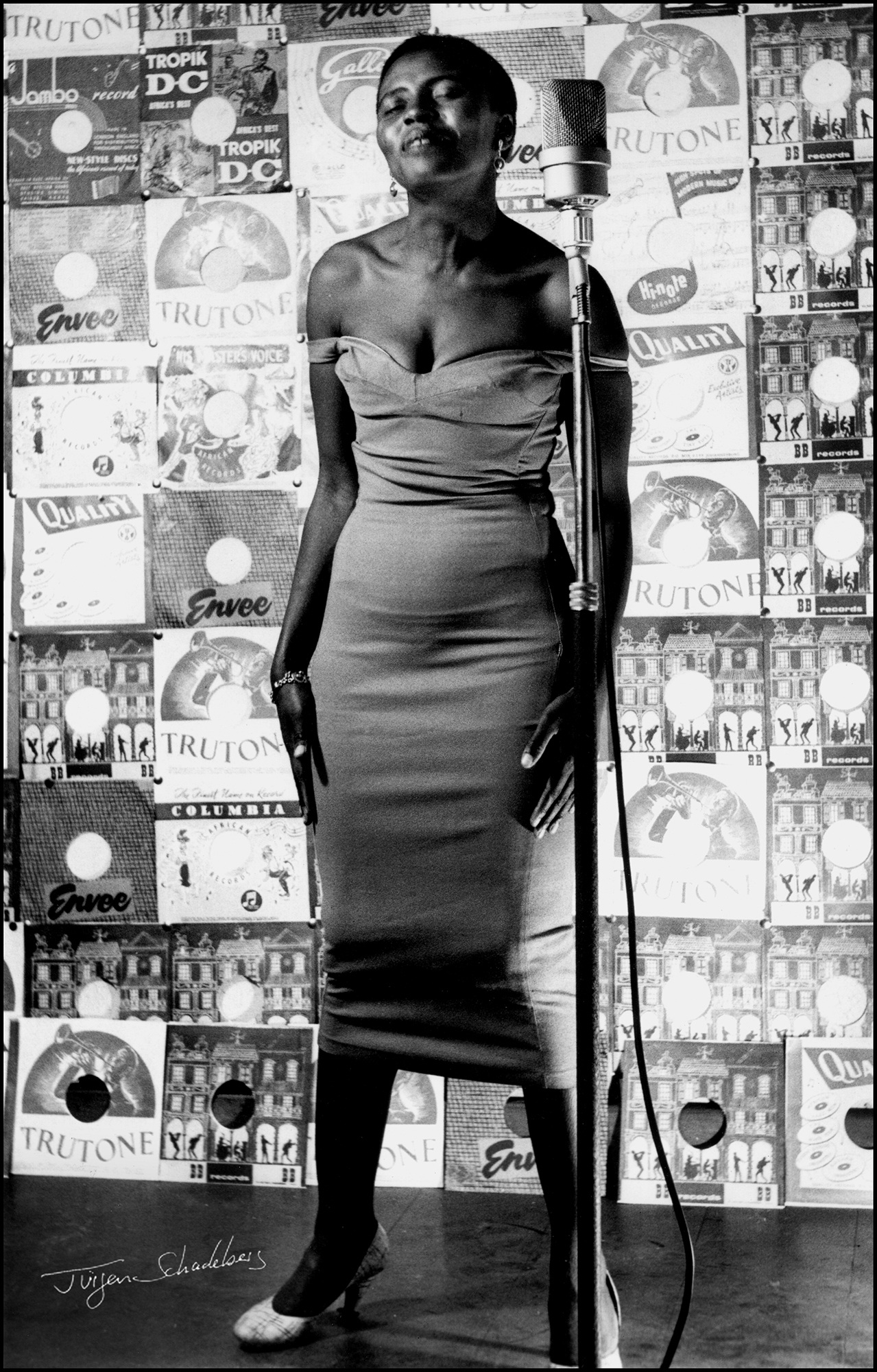

“The exhibition illuminates how fashion, alongside visual arts and music, played a pivotal role in Africa’s cultural renaissance during the independence years and how those elements laid the foundation for the radical transformation of global fashion,” explained Ernestine White-Mifetu, the exhibition’s Brooklyn Museum curator, during a recent exhibition preview.

Originated by the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, “Africa Fashion” represents the largest exhibit of its kind to hit the United States. It begins with Africa’s independence years, from the 1950s to the 1990s, and extends to the present. While designers from all 54 countries are not represented individually, White-Mifetu tells CULTURED that the exhibit aims to address each region.

The experience is soundtracked throughout by music from the continent, with an extended playlist available online. “The music relates to what’s happening at the time and brings you into how these designers are working with these materials and working in this space,” says Annissa Malvoisin, who co-curated the exhibition with White-Mifetu.

A section on the vanguards of African fashion features the work of Kofi Ansah, Naima Bennis, Chris Seydou, Sidahmed Seidnaly, and Shade Thomas-Fahm. These pioneers found ways to incorporate the traditions of their respective countries into changing cultures. Thomas-Fahm, for example, adapted the gele, a traditional, wrapped headdress, and the rapa, a style of draped clothing, for the modern-day woman by adding zippers and other streamlined elements. “Those vanguard designers were looking at fashion in such a nuanced way,” says White-Mifetu.

Another section offers a survey of contemporary designers, like Tokyo James, Orange Culture, Nao Serati, and Rich Mnisi, who are putting their own twists on traditional forms. At its best, these looks feel like a maturation of the timeline laid out earlier in the show. A glittering, white couture dress from Cameroonian designer Imane Ayissi, for example, is made completely from barkcloth that is treated to appear as a luxe and expensive fabric. (About 80 percent of the designers in the show are also represented in a special retail shop curated by Lagos concept store Alara.)

“We believe this exhibition actively complicates what people assume African fashion might be, which includes ankara or kente,” says Malvoisin, referring to a fabric also called Dutch wax, which has become a trope of designs from the continent. “You’re definitely going to see ankara. You’re definitely going to see kente, but you’re going to see it reimagined in so many ways. You’re going to see it mixed with contemporary designs.” Nigerian designer Lisa Folawiyo, whose work is included in the show, transforms the fabric with sequins and other adornments.

The Brooklyn iteration of “Africa Fashion” is twice the size of the V&A version and incorporates diasporic voices by including designs from the likes of Papa Oppong, Christopher John Rogers, and Aurora James of Brother Vellies. The diaspora makes up for the lion’s share of the 50 works that were added to the exhibit.

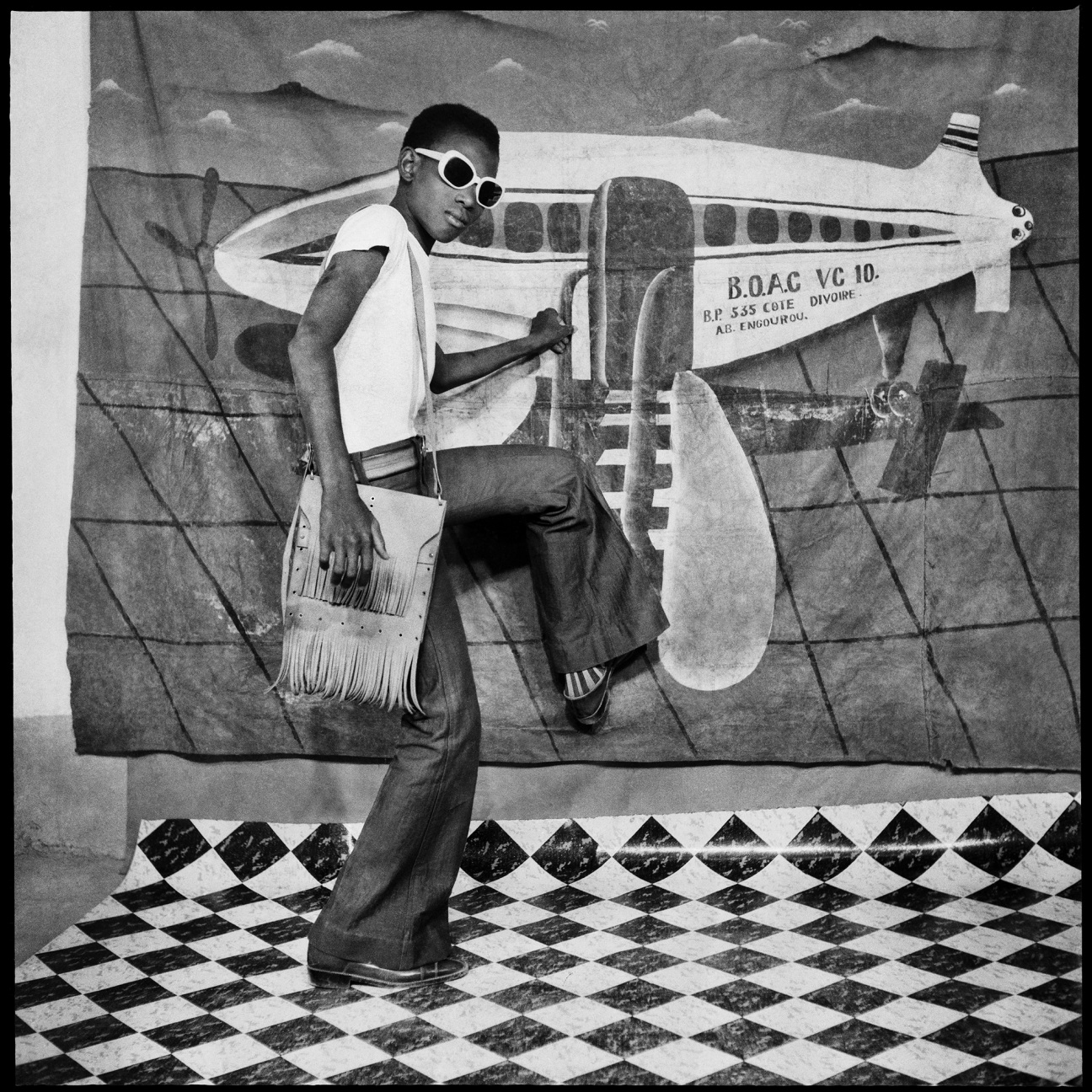

Most poignant of all is a small section of images sourced from African Americans and other individuals from the diaspora. Curators issued a call for photographs from the ‘50s to the '80s that capture “self-fashioning”; they chose about 20 responses to display. The grouping takes styles and textiles seen in the rest of the exhibit and makes them personal in a way only a faded family photo album can. In one snapshot, a Guinean family sits for a portrait taken in Niger. In it, Begaly Keita wears wide-leg trousers next to his sister, who is sporting a Dutch wax-print dress and headwrap, and other relatives wearing leppi, a handwoven, indigo-dyed cloth. In another image, from 1962, members of the Togolese Women’s Union walk through the ornate halls of the Russian government wrapped tightly in kente cloth.

“The family portraits absolutely show the importance of fashion to us in global Africa,” says Christine Checinska, the V&A’s “Africa Fashion” curator. “Wherever we travel, wherever we’ve been sent, we’ve never lost that appreciation for beauty.”

“Africa Fashion” is on view at the Brooklyn Museum in New York through October 22.

in your life?

in your life?