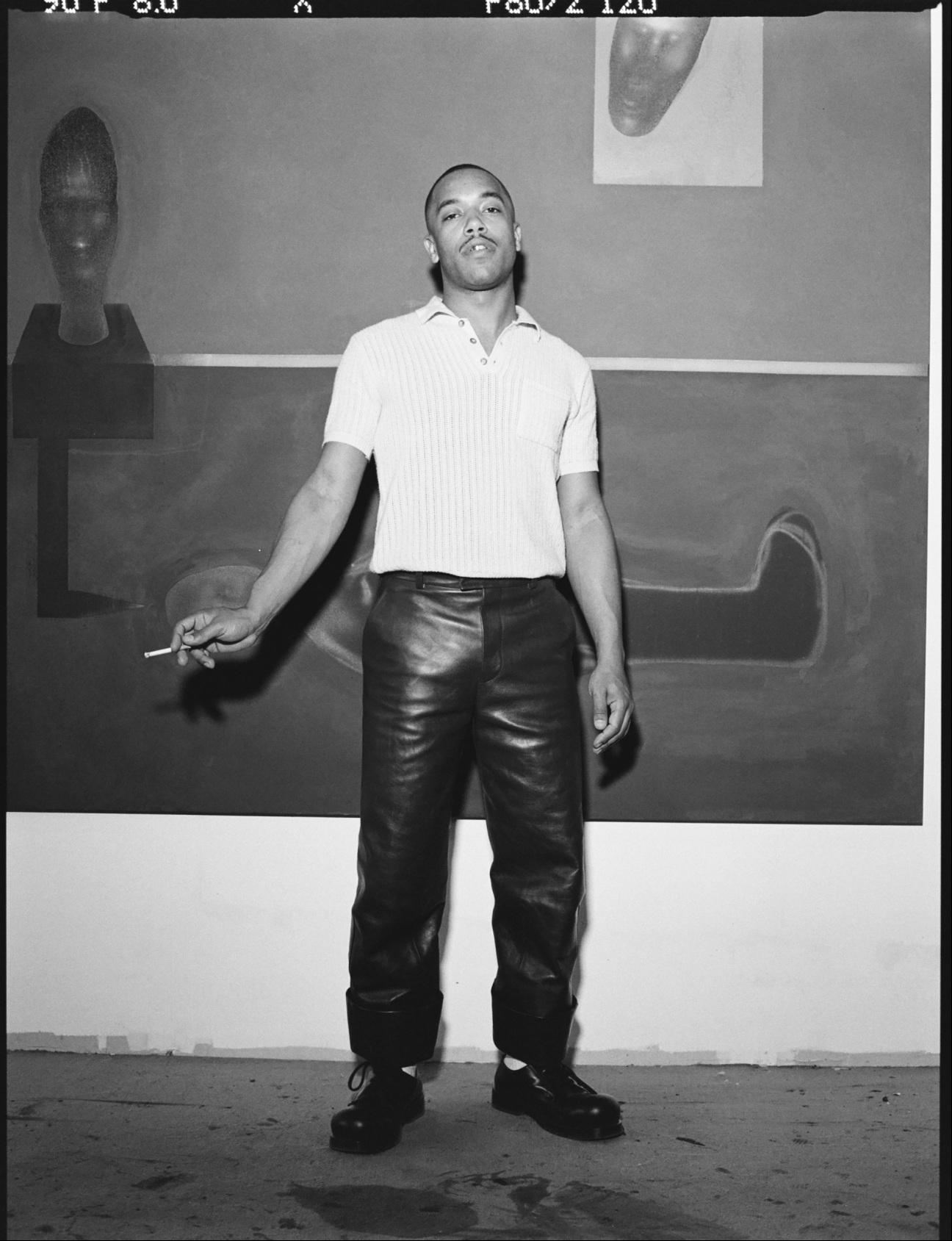

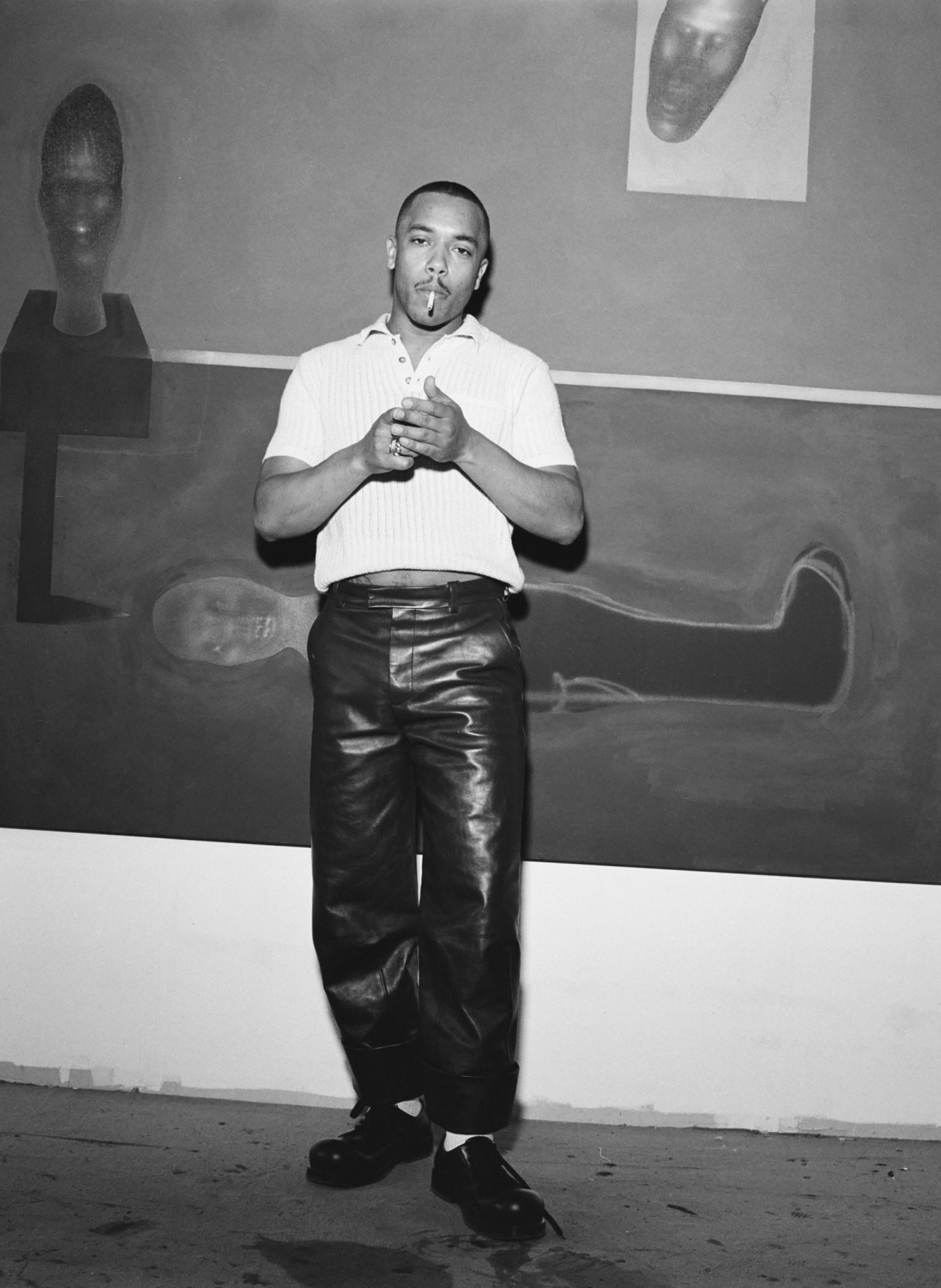

Pol Taburet is a homebody. The 26-year-old artist loves looking out of the window of his apartment and observing the petit théâtre of Parisian life. Sitting on his couch and taking drags from a cigarette across the screen, he says he sees his paintings as windows too. Or TV episodes. The show that comes to his mind is Friends. “The one who arrives at the apartment, the one who met so and so…” he explains. The screen is a major reference for Taburet, who, along with Piero della Francesca and German Expressionists, cites South Park and Disney movies as influential. His practice doesn’t include research per se, but rather observing his own life like a television series and painting from his perception of it with almost psychoanalytical distance. He fuses this perspective with an interest in the extremes of the human experience, which he archly translates into hallucinatory paintings and sculptures that speak to “the life of an object.”

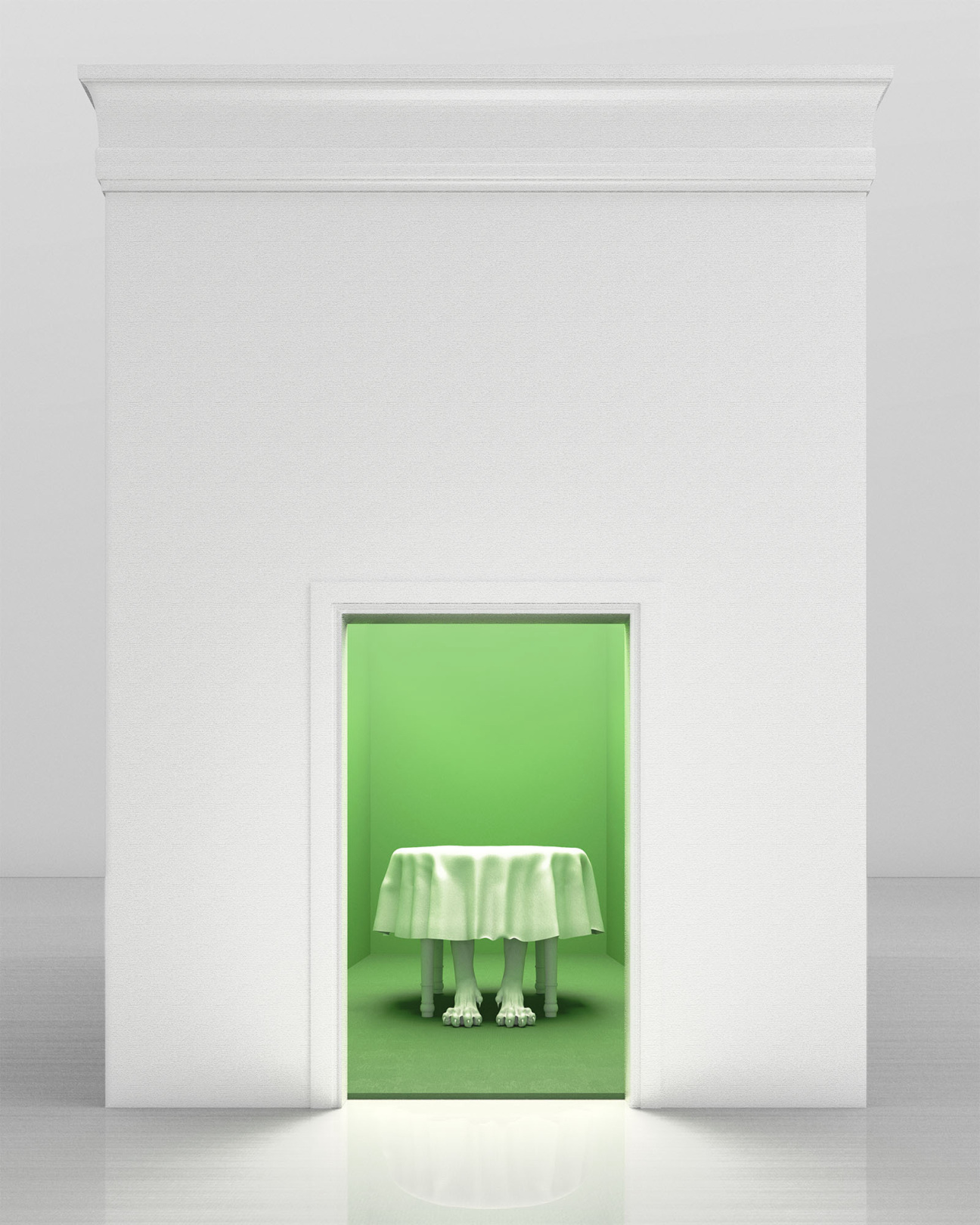

Alice in Wonderland might be the text that dialogues best with Taburet’s first institutional solo exhibition, “OPERA III: ZOO ‘The Day of Heaven and Hell.’” The show opened at Lafayette Anticipations in Paris this week, and it is a trip (in all senses of the term) into the artist’s underworld. It is echoed by a solo presentation at Balice Hertling, "Echoes from us," on view until July 13 in Paris, and Taburet’s inclusion in a Florian Krewer-curated group show at Michael Werner, “BIRDS FOLLOW SPRING,” which opens tonight. To mark the artist’s momentous summer, CULTURED chatted with Taburet about defiguration, beautiful vices, and the backlash that comes from exposure.

CULTURED: Let’s talk about “OPERA III: ZOO ‘The Day of Heaven and Hell.’” What was the genesis for the show, your first institutional solo exhibition?

Pol Taburet: There's one piece that really set it off, and that’s Belly, 2023, the bronze [and steel] fountain that’s one of the show’s centerpieces. I'd been invited to Lafayette Anticipations to do an exhibition that was supposed to be a group show about luck. I wanted something very direct, so I came up with the idea of the fountain in which you throw coins. I also wanted the fountain to look like a roulette [wheel] you’d find in a casino.

Rebecca Lamarche-Vadel, the director of Lafayette Anticipations, really liked the project, and they offered me a solo show. I was really excited about the idea, but I was also really scared to get involved in such a large-scale project, which had to be so carefully thought out. I'm used to producing things au feeling, by instinct. And painting is a very solitary act. I had never had other hands touch or help me with my work.

When they proposed the solo, my idea was to create a sort of living space, a fantasy home, kind of like living in a cartoon. I wanted to create this giant vivarium and force the viewer to have the same perception of my paintings that I have.

CULTURED: There's a tension in your work between nightmare and fantasy. With “OPERA III,” you’re bringing these contrasts into the domestic space, haunting it almost. What about the home is so compelling to you?

Taburet: I use the home as a tool. Everyone has an idea of what home looks like. I wanted to use this extremely common form, a place associated with protection and security, and inject it with a sort of interior nightmare. And the figures in the work don’t really have genitalia. Blurring that detail gives the viewer an easy entry point into the image, without being polluted by political motifs or signifiers. I want the work to be legible through a child’s eyes, for them to see something joyful and fun inside of it, and for adults to have a much more intense understanding of what’s being presented.

For example, there are paintings that show coupling in quite a direct way. In one, there are two dog-like figures making love on a road. When you look at it through adult eyes, there’s a very bestial side to it, but I don’t think children would necessarily notice. That quality opens up the work to many different eyes and generations, which I hope will make the work last longer too.

CULTURED: Figurative art has saturated the market in the past few years. The way you speak of your figures makes them seem more like vessels onto which you can project whatever you want, without being linked to a specific identity. How do you dialogue with this movement toward figuration?

Taburet: I feel like figuration is about to reach its peak. I see it moving toward something more punk or “acid” in a way. I’m trying to anticipate that by starting to remove figures, or integrating them fully into the color of my backgrounds so they become more of a vaporous entity. I often merge them with an object or a color, too. I’ve always worked between abstraction and figuration, which you can find in the compositions I make where I have these blocks of color that divide the canvas and create compartments of sorts. For me, these are spaces to contemplate color. When you see the paintings in real life, they emit this vibrancy thanks to the colors. From a distance, the figure becomes a stain that blends in with the background, and the painting almost becomes an abstract landscape à la [Mark] Rothko.

CULTURED: I don’t think figuration will ever go away, but with this more “punk” movement, I wonder if you think we might be moving more toward defiguration?

Taburet: It’s funny because that was kind of the idea behind cubism. They had worked figuration to the bone. You go from [Giorgio] Morandi, who’s painting more and more Roman vases, with more abstract backgrounds, to those who just broke figuration up completely, at least on the structural level. And then there’s [Francis] Bacon, who’s ripping and tearing up faces. And I think we’re coming back to that point. We tend to see monsters in figures like his, but I don't think they're monsters at all.

It reminds me of Ye’s album My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy, [2010]. It’s a beautiful album title, and it speaks of a beautiful vice. In a way, “OPERA III” is imbued with that feeling. With the floor and the carpeting, you have this sensation of comfort. Then the sculptural faces have this harsh, rigid aspect, sowing discomfort, and their proportions—and the space’s—are so big that you feel small.

CULTURED: You spoke about the casino earlier with Belly, but what you’re saying is also making me think of the adrenaline and roller-coaster effect we associate with that space, the desires that fill it with both innocence and perversion. You also mentioned these blocks of colors a minute ago, and I’m wondering if there are any colors that speak to you particularly at the moment?

Taburet: I want to move more towards browns, greens, darker shades. The color that’s really appealing to me right now is purple, and what it triggers in the viewer. It’s the color of twilight, transitions … the moment when night arrives and a sense of strangeness begins to set in. It’s also quite sexy, velvety, weird, and soft. I had never used purple in my paintings before this show. I think it creates a dialogue instead of overwhelming the other colors.

CULTURED: Your work is also imbued with a certain interiority and opacity, like a defense mechanism of sorts. What’s your relationship to mystery, both as an artist and as someone who’s been in the public eye since quite a young age?

Taburet: It's true that in my paintings there's something about not saying too much, and showing not telling. There's an element of wanting to seduce the viewer, flirting with them. I insert tons of little references in my work; I see my paintings as little poems that tell stories. Not wanting to intellectualize my work creates an expressiveness.

I didn't think my work would be so quickly received and embraced in such a public way, from my very first show. I didn't have time to compose a precise vision of what version of my work, and myself, I wanted to show. I was also very quickly visually exposed with magazine covers and features. So I try to give as little away as possible in my work, because I want to show for a long time. “OPERA III” is just the beginning of something.

CULTURED: Does the exposure ever feel like a double-edged sword?

Taburet: The first few times it happened, my ego took a spin. You get starstruck and so happy. The only word I can think of is “cool.” But then I had this sort of backlash, this moment where I was like, “Fuck, people are going to get attached to my face and not to the work itself,” which would consume the work very quickly, turning it into a fad. For the moment, I’ve been lucky to not see an impact on the quality of my work. The pressure makes you produce a lot more; certain things get priority over others. Now, I’m much more selective even with the press I want to do. There have been some incredibly annoying things said about me in the past, like comparisons to [Jean-Michel] Basquiat, which are so ridiculous and quite violent. My work has nothing to do with Basquiat. The only thing that's similar to Basquiat is my skin color.

I bust my ass all the time, I take very few vacations. There’s a huge demand from the galleries, and it’s at a cadence I just didn’t know before. This happened to me when I was 23. At that age, you’re just a kid. To be in this dynamic of monetization and understand how the art market works that young, it’s really brutal. Fortunately, I’ve been supported by great collectors and galleries. I was really lucky to meet [François] Pinault, who really supported my work from the beginning. He noticed my work even before the galleries did, which meant that my work was taken seriously by institutions. He made sure my work was seen in the right way.

“OPERA III: ZOO ‘The Day of Heaven and Hell'" will be on view through September 3, 2023 at Lafeyette Anticipations in Paris.