This past February, Portland, Oregon, saw its heaviest snowfall since 1943. The record-setting blizzard arrived the same week as two other local milestones: the 10th anniversary of Adams and Ollman, one of the city’s most influential art galleries, and the 50th birthday of its owner, Amy Adams. These factors swirled together one Saturday afternoon as friends and fans braved the icy conditions for the gallery’s celebratory exhibition. Prior to the opening, Adams cleared the space’s snow-covered sidewalk wearing a polka-dotted Balenciaga party dress, metal shovel in hand.

Bundled visitors arrived in the early afternoon; they were punctual—a perk of Portland’s small town intimacy. A generous spread of Vietnamese snacks and champagne awaited them—a perk of Portland’s foodie expectations. Music selections were thumbed out of a milk crate holding the afternoon’s records—a sign of a thriving local music scene that continues to fetishize vinyl. Guests arrived bearing gifts, like merchants from far-off lands. Adams hugs each visitor, folding their offerings into the crush of an embrace. Her office is bejeweled with various such tributes. The bookshelf behind her desk is swollen with artist monographs, and punctuated with devotional works and grateful bits and bobs.

The gallerist is a tireless advocate and cheerleader for her artists, qualities she attributes to her mentor, John Ollman. The owner of Philadelphia’s legendary Fleisher/Ollman gallery is known for a nationally resonant program that spotlights the self-taught. Relationships are at the heart of Ollman’s business, a value he instilled in Adams, who runs her gallery more like a household than a money-making endeavor.

“We always sold to a lot of artists because they were looking at art that wasn’t part of the mainstream for inspiration,” says Adams. “Artists have always been my favorite people to sell to, and over the years, that network has grown to include curators and more traditional collectors, too.” Jasmin Tsou of JTT gallery and gallerist and critic William Pym also consider themselves descendants of Ollman’s curatorial bloodline. The three collaborate with each other as siblings might—staging shows and tackling art fairs together. This is the type of family Adams believes in: the kind where ideas are shared and everyone benefits.

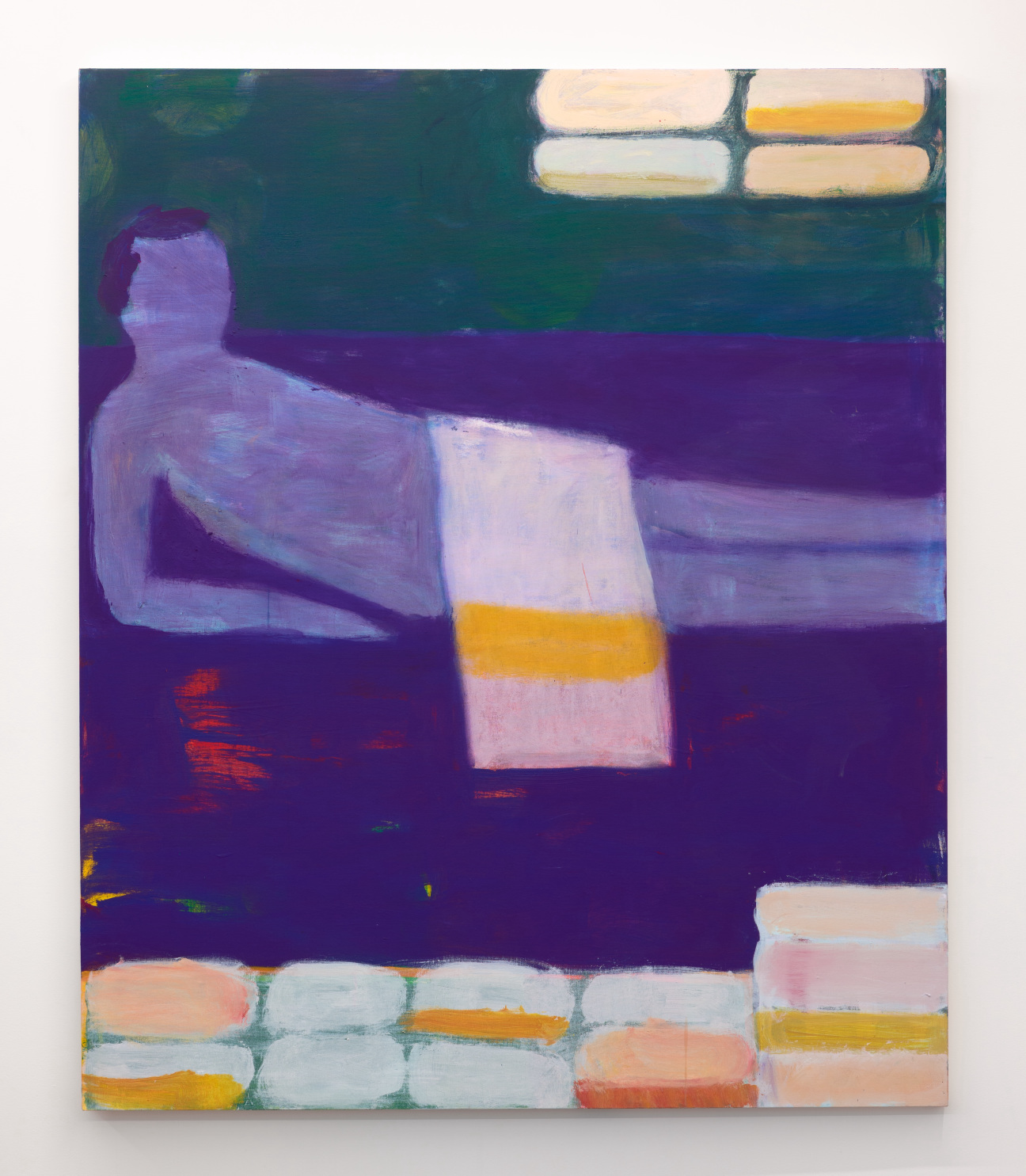

For the gallery’s 10th anniversary, Adams prepared an encyclopedic group show—which also doubled as the first time that all of her artists found themselves in the same room. She had staged an abridged version of this anniversary exhibition at Felix Art Fair a week earlier, but that night, in Adams and Ollman’s glass-fronted space, there was finally enough room to present the community that Adams spent the last decade forging in all its richness. There was a Joseph E. Yoakum landscape and a Bill Traylor image of a mustachioed man safely distanced from Kinke Kooi’s outstretched octopus arms. A large Jessica Jackson Hutchins sculpture of a jointed ceramic figure slouched over the back of an armchair at the center of the proceedings.

Portland wasn’t in Adams’s initial plan. Born on the East Coast to working-class parents, she remained in Philadelphia after school, ending up at Ollman’s prestigious but unassuming gallery by chance. In her three years there, Adams made herself essential—so much so that when her husband accepted a job in Nike’s Portland offices, Adams joked that her only option was to open Fleisher/Ollman’s West Coast outpost. In a way, she did—affixing her mentor’s name to her own and carving out a space in the city for artists who hunger for a sense of family.

“This is a small town, and I think Amy brings a lot of freshness,” said Jessica Jackson Hutchins as she turned on her studio's heaters for our visit before the opening. Hutchins made us tea amidst shards of glass and other in-progress materials. It's hard to imagine anything feeling too provincial here. But when the frank, fast-talking, politically rambunctious kiln queen observed that everyone in Portland’s art scene knows each other, I began to wonder what it would be like to jump onto a group call. Hutchins is arguably one of the most internationally visible artists working in Portland, but she abstained for years from teaming up with the city’s stalwarts. When she joined Adams and Ollman in 2020, it was a vote of confidence. Since this joint leap of faith, a series of delightfully experimental shows have added a new dimension to Hutchins’ career.

As the party waned, lingerers emerged. Writer and filmmaker Arthur Bradford, the son of iconic figurative painter Katherine Bradford, leaned over to Adams’s son, Emmett, who he’s known since he was baby, and jokingly told him as much. Emmett blushed. The two sons, who stood side-by-side with their hands in their pockets, are a testament to the years-long relationships that underpin Adams’s gallery.

Bradford and Adams’s friendship stretches all the way back to the latter’s days as an art student, when she took Bradford’s painting class at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. It blossomed further when Adams made the move to Portland and opened the gallery. “When Amy [opened the gallery], I encouraged my son to go over and introduce himself,” recalled Bradford. “At that point, I was more of a struggling artist than I am now, and I wanted to connect with her. Being the sweetheart that he is, he did.” A year later, Adams showed the artist’s work for the first time; another show soon followed. The two have worked together ever since.

If Bradford started showing in Portland out of familial convenience, she stayed for the laughs. “It's really important to me to belong to a group of people that are laughing, kind, supportive, and interesting to be with,” said Bradford. “It's just the way I wanted to be an artist, and that's not what you're going to find at all galleries.” Since 2013, Adams has placed Katherine's work in esteemed institutions including the Brooklyn Museum of Art, the Portland Museum of Art, and the Menil Collection in Houston. Bradford gives Adams a lot of credit for her overdue recognition. If a rising tide lifts all boats, then Adams is the ocean.

Without the moon to spur her forward like the tides, Adams finds the energy to do it all in the work itself. The gallery’s program reflects her own holistic approach to art. “What interests me is Conny Purtill who has been making his art for 15 years and does it for nobody but himself; or Vaginal Davis, whose paintings are plastered all over her flat in Berlin because she lives among her work,” said Adams, outlining the contours of her taste. Like Purtill and Davis, Adams lives in her work. Adams and Ollman isn’t simply a business venture—it’s a lifeline tethering like-minded makers, no matter where they reside, to a cozy idyll on the Pacific coast.

in your life?

in your life?