For his recent solo presentation with Victoria Miro Gallery at Frieze Los Angeles, Doron Langberg, 37, exhibited a suite of oil paintings of flowers in the mountains of Israel, where he grew up; of friends and lovers napping in the dunes of Fire Island, New York, the iconic queer and artistic holiday destination where he spent last summer; and of passionate sex.

His practice involves a rhythmic back-and-forth with the outdoors; many of Langberg’s paintings begin as smaller works made en plein air and later evolve into the grand, vibrant works he’s known for creating. A symphonic little study of a sunflower bush in a ditch outside his family home—one of the only plants to survive the rainless Israeli summer that year—was painted outdoors on a French easel. Afterward, he made a much larger version in his studio—Sunflowers, 2022. The arid tangle is rendered in scraggly, dry brushstrokes, and the thick paint is sanded out in places, leaving patches of pale air and giving the grass a ghostly surface quality.

On Fire Island, Langberg painted wild hibiscus bushes, long grass in the infamous Meat Rack cruising woods, and intimate close-up portraits of his friends on the beach—outdoors on an easel once again, but this time with thick, vibrant strokes of rich crimsons, magentas, fuchsias, and muddy browns. Back in the studio, beginning on the floor, he coated another canvas with a thin film of turpentine from a spray bottle and swept bold, gestural brushstrokes with big calligraphy brushes and diluted oil paint over it, creating an Abstract Expressionist backdrop for his sultry, dancing Hibiscus, 2022.

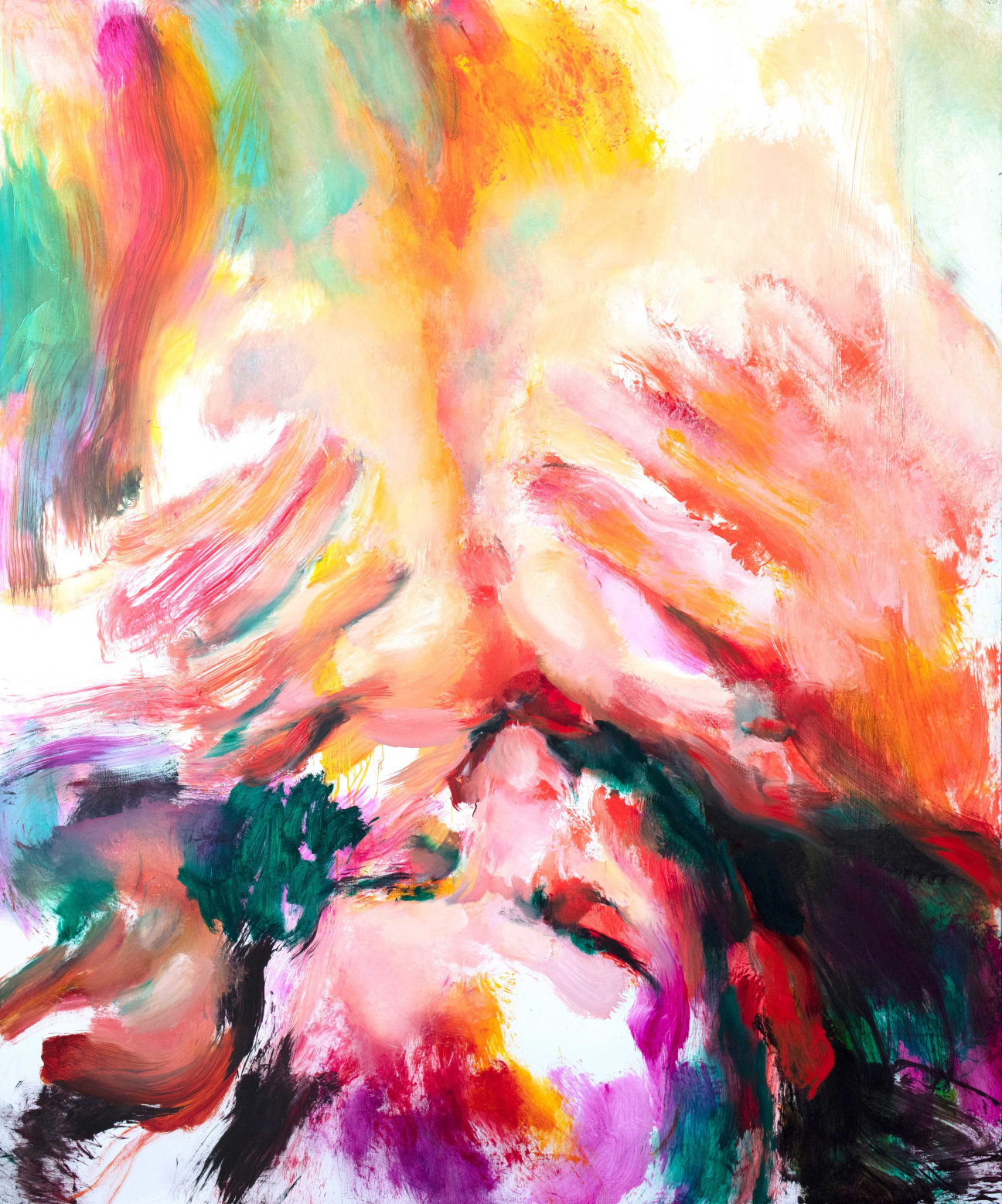

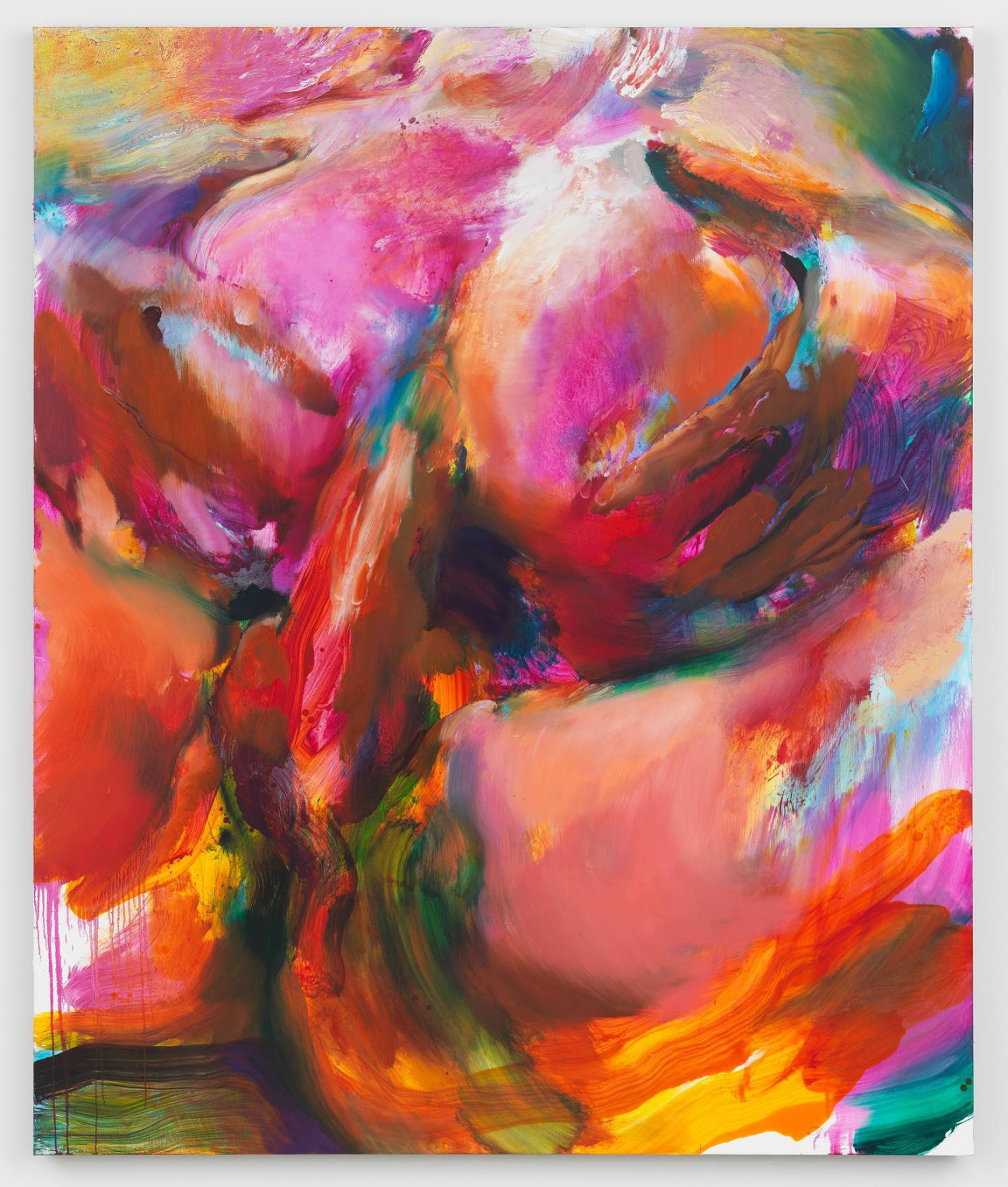

After the turpentine had evaporated, he moved it onto the wall and continued to apply heavy, confident bursts of color. Another favorite from his Frieze booth, Lovers at Night, 2023, shows two men sleeping. A murky, moody green scraped across the canvas by squeegee is foregrounded by fragmented bodies, their soft, liquid, dreaming flesh melting into messy abstraction. And lastly, there’s Lovers 1, 2022: a technicolor cacophony of thick, gestural smears, splatters, and drips.

We speak in Upper Manhattan, during golden hour. Amber light reflects in the skyscrapers downriver. Langberg wears a vest; he has a sweet, boyish face and tousled hair. His apartment is incredibly hot (I say this as someone who keeps a sweltering apartment myself). Against the backdrop of the illuminated city, as day turns to night, he talks passionately about his love of painting and how he arrived, along a winding path, as one of the most talked-about stars of figurative painting’s new wave.

He was born in 1985 in Yokneam Moshava, a bucolic suburb of Haifa in northern Israel, in a valley on the edge of Mount Carmel. His parents were professors, and their neighbors kept cows and sheep. He began documenting the wildflowers there only a few years ago, but he has been painting since he was 6. His schooling was thoroughly focused on the arts, and even in high school, when he had not yet come out as gay, much of his work was nude self-portraits. “It’s this idea of representing myself and my body,” Langberg reflects. “I almost took for granted that it would be a vehicle to express my interiority.” Conscription is mandatory in Israel, so from 18 to 21, he served as an airplane mechanic in the Air Force, which he hated. But he was stationed in Tel Aviv and was able to take weekly painting classes with the very traditional, hyperrealist painter Aram Gershuni. “I came to class in my uniform,” he recalls. “It was very silly.”

Langberg moved to the United States to study at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia, which is also rather academic and traditional. He got his first studio as a junior and began working with specifically queer subject matter, a journey that started with an erotic home video. “Around 2009,” he recalls, “I went home for winter break and hooked up with this guy, a friend, and we recorded it just for fun. When I got back to my studio, I was looking at it and I thought, I really want to paint from this.”

He had long been obsessed with Edgar Degas’s free-form Impressionist sketches of ballerinas and Parisian life, in which a rough scribble might morph into a scene in the background and a face might appear in a corner. For Langberg, the home video dovetailed perfectly with the formal concerns he found in Degas, as it featured “these entangled bodies, one in front of the other.” It brought up the same questions of negative space and figure-ground relationships he had already been thinking about. Langberg made some small graphite drawings from that video, and everything fell into place: the form and the content. He keeps many of the same concerns today—a love for art history’s great Modernists, depicting private scenes of gay life, the people that matter most to him, and the workings of human desire.

After Pennsylvania, Langberg went on to study at Yale University, where he encountered a much broader range of artistic practices and had a good support system. After graduating in 2012, he moved to New York with a bunch of friends from school, sharing a studio in the same building in Ridgewood, Queens, where he still works today. In addition to his solo booth debut at Frieze, Langberg has an exhibition up at the Rubell Museum in Miami that is on view until November, and he will open his soon-to-be-announced first solo European museum show next year. But it didn’t all happen overnight. “Oh,” he smiles, “there was a long, quiet time.”

When Langberg graduated, art was dominated by process-based abstraction. It was a time when few in the art world were thinking much about the figure. “Figurative painting was super cringe,” he recalls. “You could not talk about intimacy or connection; those things were just not present in the conversation. No one cared, which was, in retrospect, liberating. But at the time, I took it very personally. I didn’t understand why people didn’t care.” Bur rather than becoming a process-based abstractionist bro (and honestly, judging from the bright turpentine-spray-and-calligraphy-brush grounds of his Hibiscus paintings, he could have been a great Abstract painter), he leaned deeper into his instincts, continuing to work with oils, returning to painting from observation after having stopped for a few years, and dedicating himself to mastering his craft.

The abstraction craze fizzled out after a few years, but it was only in the late 2010s that, somewhat unexpectedly, figurative painting returned—taking hold of the market and the museums. Langberg was as surprised as anybody, but he and many of his painter friends see a return to figuration as connected to the deteriorating political situation in the U.S. and beyond. “The more people feel infringed upon, the more urgent that conversation becomes,” he says. “When you’re thinking about work that deals with identity—whether it’s sexuality, or race, or gender—when you experience push back in your personal life, it motivates you to look at those aspects of yourself and think deeper about them.”

Langberg believes a great painting connects you to the artist in an immediate way, capturing what it means to be that person like no other object can. “It’s the manifestation of another person’s desire or what they think is beautiful, or sexy, or touching, or sad, or crushing, or important,” the artist says. “Seeing another person through their paintings, or seeing the person an artist depicts through their paintings, is incredibly touching and powerful.”

For him, this quality of presence is deepened further by the queerness of the work. “Growing up with the perception of something that’s so deeply connected to every other part of you,” he continues, “really made me want to assert the fullness of that experience—and how layered it is, and how beautiful it is—in the clearest way I can. That’s a big reason why I’m so specific and explicit with the sexual work. It’s absolutely pornographic, but that is part of our everyday experiences.”

This brings us back to Lovers 1. Langberg thinks it is the most explicit painting he’s made, and he has made some very explicit work. It is a giant close-up painting of two men fucking one another, from behind, rendered in big, joyous brushstrokes in every sour-candy-color of the rainbow swirled rapturously together: like a J. M. W. Turner storm inside an acid Malibu sunset, or a neon Willem de Kooning painting of an asshole. Langberg has said before that he admires Pierre Bonnard, and that “what’s masterful about him is that he really uses every color in every painting, and trying to balance this rainbow palette is really almost impossible.” For Lovers 1, he has thrown the full-blown, vivid palette into the action himself. The painting was kicking around in his studio for a while before the artist could make it harmonious, before he felt it was worthy of its subject.

“The stakes are so much higher when it’s an explicit painting. You can make a shitty painting of flowers, but you can’t make a shitty painting of guys fucking,” says Langberg. There is a greater sense of responsibility because this is not a scene you see a lot in the world. It also has an intense shock value, but his intention is not to be shocking. “In order to show and talk about what I want to,” he says, “without that message being derailed by the fact that it’s a really explicit image, the painting has to be really strong.” It has to be bold. It has to be honest and true.

There has only been one time that Langberg made a sex painting from observation. Two good friends hooked up in front of his easel. “That was a really beautiful, intense experience that I loved,” he recalls. But the rest are from photos, some of which he has taken himself. Every painting he makes is connected to a personal experience, and all of his formal decisions stem from a desire to articulate those experiences. As an artist, his greatest aspiration is to make work that resonates with people.

I wanted to profile Langberg because I like how lascivious—how hardcore and passionate and desiring—his paintings can be, and I believe we need more of that in art and in life. We should be evangelizing desire. Near the end of our conversation, I ask if he thinks about fucking when he is painting. Without missing a beat, he tells me a story about a former student coming to visit him in his studio in Ridgewood and asking, “Do you just think about sex all the time?” His answer was, “No, I think about painting all the time.” He continues, “It’s very important to be as close to painting as possible. Even during sex, painting is the lens through which I experience the world. And in my mind, those moments that are particularly meaningful, or emotional, or beautiful, or sexy, all go through painting as an experiential filter.”

Let’s finish where we began, in the flowers. Langberg says that flowers—like the ones he’s been painting in the mountains and in the bushes by the sea for the past few years—are probably his most indulgent subject matter. “There’s a real kind of giving in to how beautiful painting can be and how beautiful flowers can be,” he concludes. His sex paintings, his loving portraits, and his flower paintings are all connected by gestures of pleasure and longing; and full of the powerful desire and beauty that is too often missing from life.

in your life?

in your life?