Jonathan Carver Moore understands that a good story connects the deeply personal to the universal. His gallery offers underrepresented voices a safe space to tell their own—it’s the reason why his artists trust him, and why his eponymous gallery, which opened on March 23 in San Francisco’s Tenderloin neighborhood, has been overrun with visitors.

Moore anchors his gallery program in the power of shared experiences and the intersections of race, sexual orientation, and gender identity. “When you are part of a marginalized group—and have been treated differently based on how you identify or present—there's a natural connection,” he says. “When I have spoken to these artists, it's almost like they are able to breathe; they don't have to explain things to me because they can look at me and know that I get it.” Some of the artists in his program have waited a decade or longer for the right person to show their work; with Moore, they feel seen.

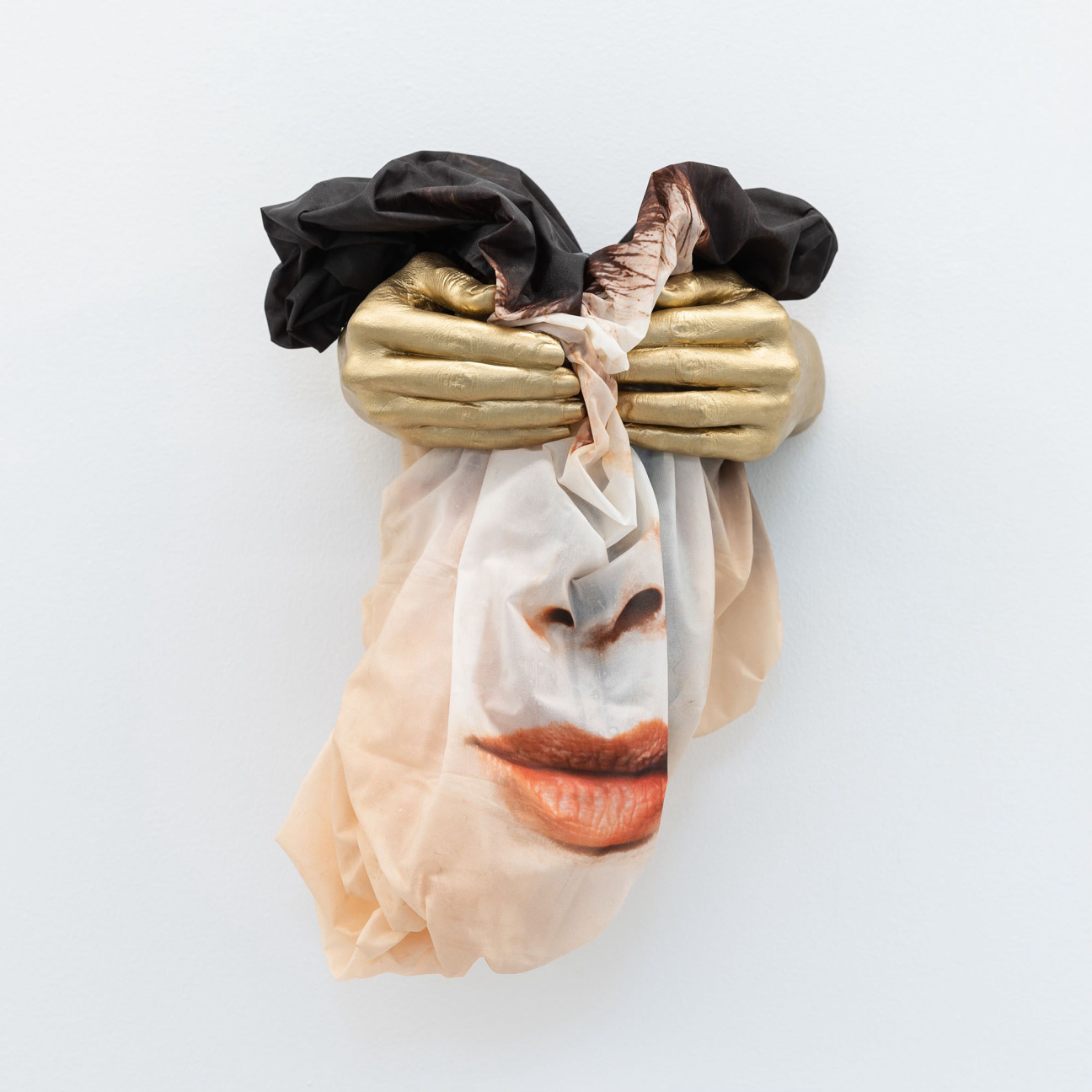

Located in an industrial storefront space with wide windows that flood the gallery with natural light, Jonathan Carver Moore opened its doors for the first time with “The Weight of Souls,” a survey of soft sculptures by Taiwanese-born, San Francisco-based artist Kacy Jung. On a brisk San Francisco evening, over 350 people flocked to Market Street to celebrate. Inside, the atmosphere was one of gratitude. “Jonathan gave me this chance and platform to showcase my work the way I want,” says Jung, who was surprised by the number of guests who saw their own stories reflected in her avant-garde self-portraits.

This is the first contemporary gallery in San Francisco to be owned by an openly gay, Black man—a groundbreaking accomplishment that highlights the urgent need for more queer, Black-owned arts organizations. While there has been a recent push for galleries to expand their representation, diversity behind the scenes has lagged far behind.

“One of the biggest things for me is taking up space,” says Moore. “When you don't see people that look like you, then you don't think it's a place that you're allowed.” He made a deliberate choice to open up shop in the Tenderloin, a diverse neighborhood and the world's first legally recognized transgender district, which the gallerist has called home since he moved to the city from Maryland seven years ago. The gallery is also less than a 10 minute walk from SFMOMA, the Asian Art Museum, the Museum of the African Diaspora, and Moore’s own apartment, where he had previously hosted art mixers.

Moore is aware of what he represents to others. “When you look in that window and see that there's a Black person in there who works in the gallery, that is important. To this day, when I go into galleries in San Francisco, I don't see those types of people,” he says. “Then, of course, if you get to know me or if you read about me, you might find out, ‘Oh, and he's gay, too.’” For Moore, these are things that shouldn't matter but do matter. “Part of me doing this is for the young gay boy in me: to send the message that just because you don't see someone like you doesn't mean you don’t belong. I'm happy to be that example for the next generation.”

Moore grew up exposed to diverse cultures due to his father’s military job, something he credits with his lifelong knack for building community. It was in museums across Europe and Asia that he discovered his love of the arts, but it wasn’t until 2019, while visiting his partner’s family in Canada, that Moore saw his identity reflected back to him in an arts institution. On a visit to the Ottawa Art Gallery, he encountered the work of South African photographer Zanele Muholi: queer, Black, and dynamic. It became the catalyst for his art education.

“It was the first time I truly saw the way I look in a museum—not just being Black and having dark skin but being Black, dark-skinned, and queer,” he emphasizes. “When I think about why I want to do this, I think about that moment.” After seeing Muholi’s work, Moore returned home and started a digital journal called Artucated to teach himself about art. “If I saw a lithograph, I would write the definition, find a work that I liked, and make a post,” he says.

The project snowballed. Moore became curious about the artists in his own community and started visiting galleries, museums, and artist studios. Before he knew it, he was bringing the work of emerging artists, including Jung, to local galleries to try to get them representation. When galleries told him the artists did not fit in their programs, he realized there was something missing in the city’s art scene.

“I looked up one day and asked myself, why am I waiting?” He credits the Bay Area’s startup mentality for giving him the confidence to start his own gallery. “I was so nervous. I was like, ‘Are people going to take me seriously?’” he remembers. “Then I thought, Wait, I've been doing this already; I just haven't put it all together.”

Now, Moore is preparing for his full circle moment: a big June group show for Pride Month featuring Muholi’s photography alongside the work of their protegees. He hopes that showcasing these works might offer queer Black viewers an opportunity to see themselves in art—just like he did five years ago.

The gallerist’s efforts to uplift his community stretch beyond the gallery walls: he has sat on the board of Root Division, a Bay Area art education nonprofit that supports local emerging artists, for the last two years—and he lists galleries Glass Rice, Good Mother, and Pt.2 as his peers. “We’re a small but mighty community. If we come together, everyone can see what the Bay Area has to offer.” This sentiment is echoed by artists eager to see more representation in the local scene. “We need more gallery owners of color in the Bay Area,” says Oakland-born artist Christopher Adam Williams. “The fact that he is Black and is part of the LGBTQ+ community makes it even stronger: he's striving to represent everyone.”

Williams has two paintings in Jonathan Carver Moore’s upcoming group show, “Black as an Experience Not a Color,” which opens on April 20, showcasing work from Aplerh-Doku Borlabi, Odinakachi Okoroafor, Steelo, Sesse Elangwe, Glenn Hardy Jr., and Williams: Black male painters from across the African diaspora. “There's this expectation from the outside audience that your art must touch on overcoming Black pain or be flamboyant or ultra Black to be relevant,” says Williams. “But that's not all life is about; there are a whole bunch of different personalities, feelings, experiences. My job as a Black artist is to convey them differently than the norm, and Jonathan gets it.”

"I can really move the needle here," says Moore when asked why he chose to open a gallery in the Bay Area instead of Los Angeles or New York, “and my community is here.” This sentiment is not lost on the artists with whom he works. “It makes it feel like things are moving in a positive direction,” says Hardy Jr.

While Moore is aware of the impact that his gallery has on the local community, he insists that the hard work has already been done: “I'm only highlighting what's already there. This community already exists,” he says. “Why don’t we all lift it up together and make it more visible?”

in your life?

in your life?