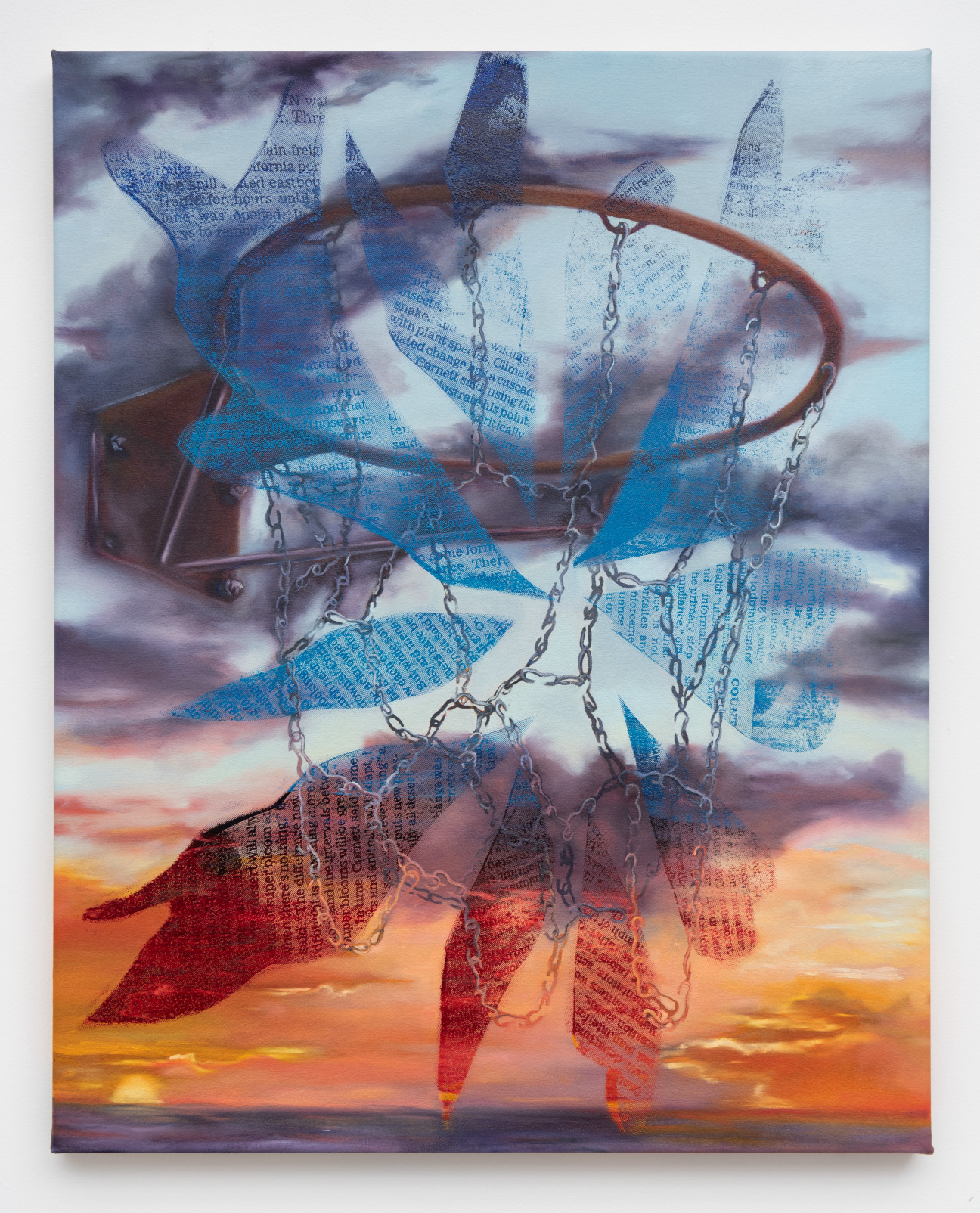

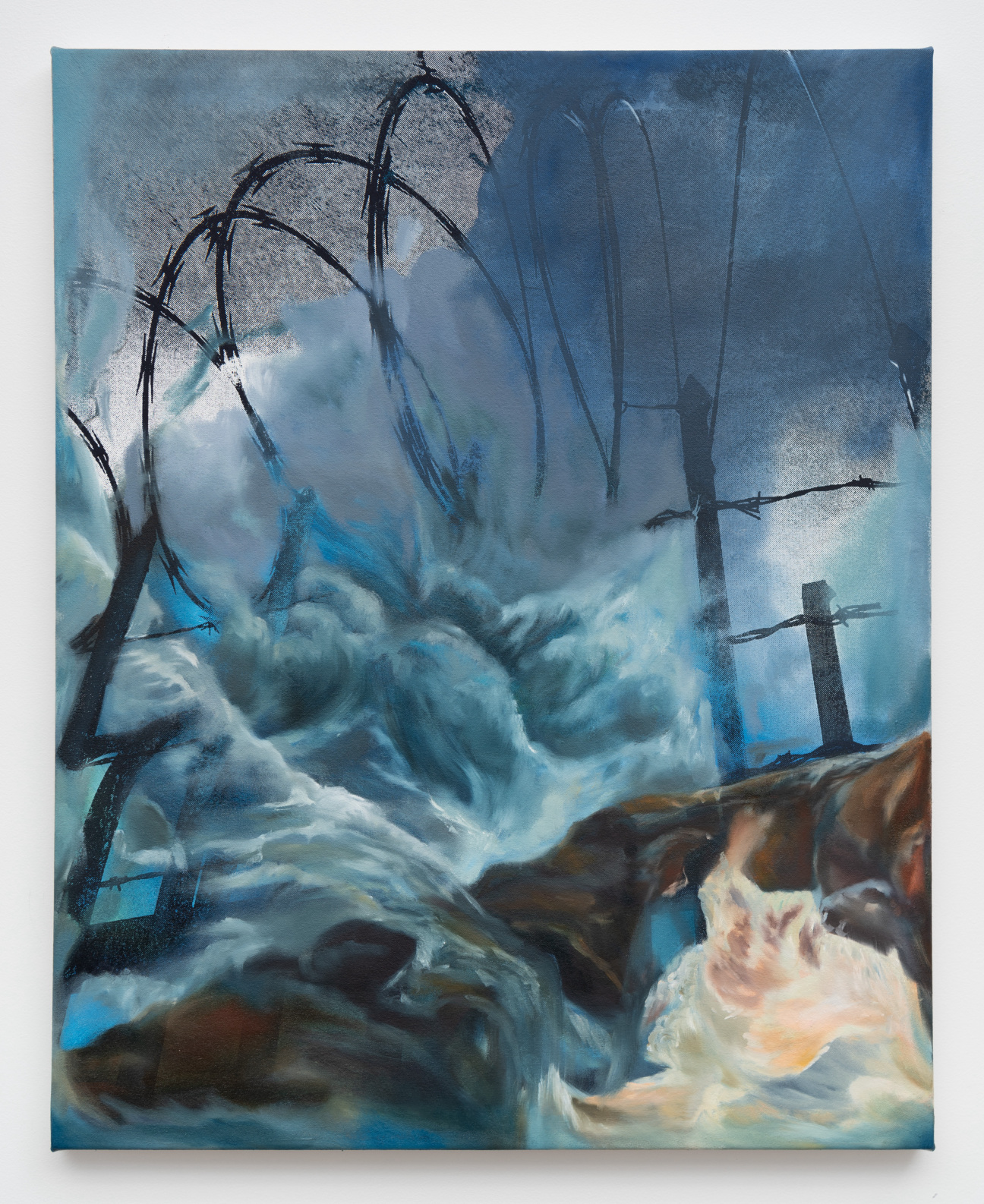

With the opening of Jessica Taylor Bellamy’s exhibition “Endnotes for Sunshine” fast approaching, the rising painter and multidisciplinary artist has been fighting the urge to cram everything she’s ever made into the sun-filled space at Anat Ebgi in Los Angeles. Ultimately she has resisted, opting to present a meticulous selection of her signature works—quintessential California landscapes overlaid with looming harbingers of climate change—instead. “There's so much I want to fit in,” she says, “but I know the results will be better if I listen to the guiding voices in the gallery.” "Endnotes for Sunshine,” Bellamy’s first solo exhibition with the gallery which opens Jan. 21st, articulates the artist’s relationship to her native city, spotlighting the structures of privilege, oppression, and environmental devastation embedded in its topography. In 2020, while a student at USC, Bellamy met Suzanne Lacy, a performance and visual artist and her fellow Californian, who likewise takes the her expansive home state’s heavy symbolism as source material. The pair first connected over their investment in the politics and practice of socially-engaged artmaking—and many zines, studio visits, and strolls down the beach later, expanded their relationship into a creative communion. Here, on the occasion of Bellamy's upcoming exhibition, the artist and her mentor discusss the shared influences—namely the urban and rural subcultures of California—that fuel their ever-evolving practices.

Suzanne Lacy: I'm so excited about your one-woman show during Frieze.

Jessica Taylor Bellamy: It’s my first solo show! There's so much I want to fit in, but I know the results will be better if I listen to the guiding voices in the gallery.

SL: When you came to USC, your brain was just wild with ideas and creativity. What was your notion of following guiding voices then?

JB: I sought feedback from everyone! But the biggest thing school taught me was when to use that feedback and when to follow the inner voice. I remember my first meetings with you when I wasn’t even sure about which artistic direction to pursue with my many interests—your advice was, “Learn how to paint.” That's when I committed to painting.

SL: Perhaps there will be an avenue into performance art through your previous social justice work. I think it is great that you have such a strong engagement with painting and studio practice, but I know you have many interests.

JB: The studio practice is my priority. I get here every day at the same time. I wear the same outfit. But my collecting and archiving reflects socially-oriented ideas. I think it's just a matter of time—and having mentors like you—that brings that out.

SL: Artists do have the capacity to reinvent themselves. The problem with getting success too early is that you can get trapped in a particular form of production. But on the other hand, with enough success—look at people like Rick Lowe—you can go from a very deep, committed social practice to painting.

JB: Working with curators or galleries that encourage those parts of your practice is really great.

SL: Let's talk about our backgrounds in California. I was born in the San Joaquin Valley, a working class rural community in the middle of California. We share that, don't we? A working class background?

JB: Yeah. I grew up in Whittier, California. No one in my family was an artist, and half the family was first generation immigrants. So it was really important to have stability. Art didn't seem like a stable path, but I was exposed to a lot of art. I had someone tell me the only way to become an artist was to marry rich, which I have not done.

SL: Well, I suppose that is one way!

JB: My grandpa was a dental lab tech, so he had all of these tools for working with glass and metal. There are pictures of me using the soldering iron when I was, like, five years old.

SL: I've been trying to figure out my relationship to my own background. My dad was a mechanic but was quite creative, filming us with a high 8 camera, painting with oils and making belts from rattlesnake hides. I’ve been exploring class in a video called “Dad Lessons.” My dad, from Appalachia, sits in his wheelchair and talks about war experiences, under a parked B-29 airplane on the 99 freeway. Where did your family immigrate from?

JB: My dad's side is from Cuba, they're Afro-Cuban. My mom's side is third-generation American, mostly from Eastern Europe. They all decided to move to California.

SL: California is prominent in both of our practices.

JB: I had a bit of a complex about it for a short time. But I realize that it is a big part of my identity, as someone who grew up multicultural. I felt very at home and accepted here. I love the visual experience that appeals to my artistry, like the sunset palette.

SL: Yeah. I went to Cal Arts and was of the American Graffiti generation [the 1974 George Lucas film about a group of teens driving the streets of small-town California in the early rock and roll era]. In fact, I grew up in the same rural region and I've been driving since I was 13.

JB: Wow.

SL: Cars have been a large part of my work. At your age I also connected with the haptic aspects of Los Angeles. I worked in Watts and would drive from Venice to Watts, and then after work to downtown LA, where performance artists were gathering. Prostitution Notes, 1974 is essentially about tracking emotional and physical territory in LA.

JB: There's something that is part of our mundane practice of driving—moving through these different spaces—that is completely fascinating. It makes its way into some humorous parts of my work.

SL: Cinderella in a Dragster, 1976 is also about cars and humor. I love the humor in your painted car parts combined with video. As a performance artist, I’m interested in how the archive of performance is re-presented as objects that carry memory of the event. Cinderella in a Dragster now exists as photographs and documentary audio, but I've been thinking about making a hot rod to represent the work.

JB: I would love to help you make a hot rod.

SL: That’s a great offer!

JB: There’s a lot of unusual and physical work, being an artist. I just brought one of my large works from the car into my studio, but it didn’t fit in the elevator so I dragged it up the stairs. If anyone at the gallery saw how I handle pieces in the early stages, they would probably pass out.

SL: I know. I’ve dragged goat carcasses up many stairs. I want to ask you a question that I think you ask yourself a lot. How do your politics fit into your work?

JB: Well, I’ll tell you about my video, Redlining Hawks (an animated memory), 2022. When my father was a child in Inglewood, he would train red tailed hawks to catch mice, rabbits, and small animals. That seemed so bizarre to me. Now, every time I’m in the car, I have a hyper awareness of all of these giant birds sitting on freeway signs, circling. I think that’s political in a lot of ways, the change in your perception of a landscape and who's living there. This memory was very matter-of-fact, it wasn't inherently political. I just thought it was magical, sad, and also fit in with the way that I approach my work.

SL: It's very poetic. I love that piece.

JB: Thank you. It all came from sitting in the car.